The author, R.H. Herron worked for seventeen years as a 911 fire/medical dispatcher. We asked her to write about the things the public doesn’t know about that job, and about the things we should all keep in mind in an emergency.

- Cell Phones Don’t Always Provide Reliable Locations

On TV, you see the screen triangulate your location with pinpoint accuracy. Oh, we wish. Up until just a few years ago, we really had almost no idea where you were if you called on a cell phone. Technology for E-911 is a lot better now, but the GPS on your phone is still only an estimation based on a lot of things that can go sideways, so when we ask you to state your location (and to repeat it, which we have to ask by law), don’t get angry. I can think of hundreds of instances in my career when the phone went dead before we got a good location. Sometimes we only ever got the right location when someone found the newly-dead body (asthma patients, especially, who couldn’t choke out the address before losing consciousness).

Know where you are at all times, including when you’re driving. Last year, I was the first person on scene after a man was hit by a speeding car, and as I did CPR on him, I realized I didn’t know the name of the street I was on. Luckily, the nearby liquor store called 911 from their landline (my hands were too busy to call, anyway), but it reminded me to be vigilant. I often test myself. I’m near the corner of Fontaine and Golf Links. Or I’m eastbound 580 just west of High Street.

Also, Google to find out how to pull your GPS coordinates (which you can give to the dispatcher verbally) from your particular phone if it becomes necessary. Don’t try to figure it out when you’re on the trail and come across an emergency.

- People Die a Lot

Dispatchers have a clearer grasp than some people that human mortality rates still stand at a hundred percent. That guy I did CPR on? He died (and I knew he would, even as I compressed his caved-in chest). 90% of those who experience cardiac arrest out of a hospital die. CPR helps a lot, of course, but still, only 45% of people who get bystander CPR intervention make it home.

People die more around the holidays, especially Christmas. One morning, during the week between Christmas and New Year’s, I gave CPR instructions to five callers in a row, and all of them failed. They were all within one hour. The last one was a baby. It remains the first and only time I ever requested to be moved off the 911 line and onto the fire radio for the rest of my twelve-hour shift.

- Why Fires Start

In what seems like a hopelessly classist overgeneralization, fires that destroy homes in low-income areas are often started by extension cords. Fires that destroy homes in high-income areas are often started by linseed oil rags (but are they’re frequently less devastating because they usually have in-home fire sprinkler systems). This startling disparity shocked me when I switched agencies from a poorer area to an incredibly wealthy city. Rich folks’ stuff doesn’t burn as much.

Pro-tip: Clothes dryers do start fires (and the two words “dryer fire” are fun to say on the radio). Once, as I advised a caller to exit the residence (for the love of God, always exit the residence! Don’t try any heroics!), I heard a bang. The caller screamed and then said, “Holy crap! My fire extinguisher just exploded! It put out the fire!” I’ve kept my fire extinguisher on top of my dryer ever since.

- Most People Don’t Say Thank You

And that’s completely okay. You’re calling me on the worst day of your life. Your husband just shot your daughter. You won’t remember that I lower my voice to a near whisper to get you to stop screaming. You get quieter so you can hear me, and I give you instructions on how to stop the bleeding while getting the description and direction of flight of your husband who just took off in his truck. As soon as the cops and paramedics get there, you’ll drop your phone, leaving the line open. I’ll listen if I don’t have to grab the next 911 call because it’s good to have an audible record if any of this goes to court later. I also listen because I’m a dispatcher. We’re all born with the urge to help.

- We Know the Frequent Fliers

The average American dials 911 once in their lives. There are people, though, who dial it more often. Frequent fliers, as well call them, often call a couple of times every day. I haven’t worked for the police agency with jurisdiction over Ronald Bilman [not his real name] for thirteen years, but I can still you his date of birth and that he has a swastika tattooed on his forehead. When an officer told me on the radio that he was going to talk to Ronald, I’d start running him for warrants before the officer asked me to. (And Ronald always had a warrant or two.)

We know who will get in a fight with their wife on the first of the month over the rent check. We know the address of every bar in town by heart. We know who will call us drunk on 911 and sing Billie Holliday songs to us, which we’ll listen to if we have time. They don’t need anything except to be heard for a few minutes, and sometimes that’s a gift we can give.

- We Don’t Care Who You Don’t Want In Your Neighborhood

If it sounds like we don’t care about the person you swear doesn’t belong in your neighborhood, it’s because we don’t. You’re being racist. I think it’s great that people are using cell phones to publicize racist 911 calls like Barbecue Becky and Permit Patty. People have always called saying things like, “I know he’s not from here. I think he’s getting ready to rob someone.” When asked why, they’re happy to whisper, “Because he’s black.” They think they’re anonymous on 911 (they’re not—911 calls are always public record). The fact that this rampant problem is coming to light now is pretty great.

- We Will Always Send You Help

We’ll send it, even if we don’t want to send you help, even if, as above, we know you’re overreacting. 911 dispatchers aren’t allowed to make the call that what you’re saying doesn’t matter. I don’t get to refuse to send you an officer or an ambulance. I’m not on scene, so I can’t know for sure what’s needed. I’ve sent officers to take reports on dreams (after September 11th, this was a problem—everyone was dreaming about terrorist attacks and wanting to “help.”) If you want assistance, we will send it. Of course, it might take days—literally—for us to find an officer with the time to go to you, and some cities don’t have the capacity to respond to things like burglaries—they’ll just have you make a report online.

I only refused service once in seventeen years of doing 911 (and my coworker was honestly horrified that I did so). A thirteen-year-old girl told me that she’d just been bitten by a tick and wanted the ambulance to test her for Lyme disease. I told her to call her mom and call me back if she still wanted an ambulance. She never called back. I did not get fired. It was a hill I was willing to die upon.

- Which Care Homes Care

Not all care homes and independent living facilities care about your relatives. Before you put a loved one in a home, go to the nearest fire station and ask which one they like (don’t call 911—we won’t talk smack on a recorded line). Some care homes are wonderful, and we can hear the love in their voices when they call for a resident who’s fallen, or who won’t wake up. Others are nightmarish.

Also, in many instances, depending on the laws of your state, the nursing staff might not be allowed to perform lifesaving care on your loved one. I’ve often begged staff to start CPR on a patient who’s just gone down in a hallway or dining room, and they refuse because it’s their protocol. This is what it sounds like. I’ve had this exact argument too many times to count. They can’t touch the patient—they can only call 911. By the time the ambulance arrives, it’s often too late to help.

- That Love Always Sounds the Same

Whether I’m speaking English to the caller or we’re going through a translator, love always sounds the same. A man trying to get his newborn baby to breathe sounds exactly like the great-grandson giving his 103-year-old grandmother CPR. Come on. You can do this. I know you can. You have to. A woman protecting her child from an abusive man sounds just like a man protecting his daughter from an attacking dog.

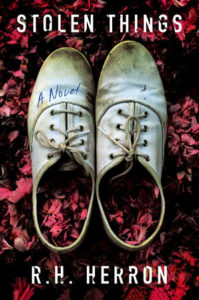

Love is fierce. Love is often angry. Love will fight. Love doesn’t always win, because life is life, and people die. But love always, always fights as hard as it possibly can, and dispatchers get the honor of hearing the fight and occasionally, helping the good guy win. And it’s this, more than anything, that I hope readers take away from spending time with Laurie, the dispatcher in my new novel, Stolen Things.

* * *