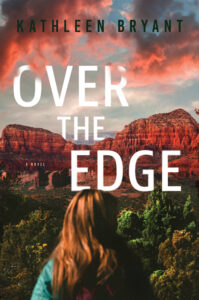

With its stunning red rock canyons and forest trails, Sedona, Arizona, is the perfect getaway. This might be what you’re thinking if you’re planning a family vacation. Or if (like me) you’re plotting a crime novel.

Each year millions of people visit this small town, known for its luxury resorts and outdoor recreation. Miles of trails lead into Coconino National Forest, winding among colorful sandstone formations bearing charming nicknames: Teapot, Snoopy, Elephant Rock. It’s a little like a Disneyland for hikers. (And locals are quick to tell you, Walt Disney did own a vacation home here for a while.)

But even a cartoon-shaped rock casts a shadow. Rattlesnakes, rockfalls, flash floods, lightning strikes. Experienced hikers know they share the trails with natural hazards. And yet the savviest travelers—lulled by the landscape, soothed by Sedona’s reputation as a spiritual mecca—can be blithely unaware of its unnatural hazards.

If you approach from the west, a red-and-gold curtain of cliffs sweeps across the horizon to fill your windscreen. Why not pause at a scenic overlook to enjoy this panorama? In January 2012, a pair of travelers did just that. Perhaps they stretched their legs in the surrounding forest or lingered to watch sunset. The next morning, their Subaru wagon was still parked in the same spot, surrounded by broken glass and .223-caliber casings, passengers dead inside.

The last time I stopped at this roadside parking area, browning weeds had sprouted from the asphalt, and it felt haunted by violence. Three days after these shocking murders, the suspect engaged in a gun battle with authorities. His motives died with him—so did a Maricopa County deputy.

This wasn’t the only time Sedona’s serene beauty was marred by tragedy. Twenty years of living in Red Rock Country convinced me: Bad things can happen in beautiful places.

The day I moved here, all of Arizona was on alert. A murder suspect imprisoned for armed robbery, assault, and kidnapping had escaped, triggering the state’s largest manhunt. For seven weeks, he eluded county sheriffs, wilderness rangers, and federal agents. He worked his way north from the Sonoran Desert, hiding out in the state’s parks and forests and leaving a wake of crimes. In Grand Canyon National Park, he used hostages as a shield to escape pursuers, then melted into the wilderness. He was finally apprehended in Sedona.

Almost, but not quite, the perfect getaway.

Three-quarters of Arizona is public land or tribal land. Outside of Phoenix and Tucson, the landscape is rough, dry, and wrinkled. You can get lost out here, by choice or by accident. Among U.S. states, Arizona ranks second in missing persons per capita. One of the missing is forest ranger David Miller. In May 1998, he went backpacking in the canyons northwest of Sedona and never returned.

Anyone, even experienced hikers, can fall victim to circumstance. Others are victims of crime.

Marjorie Hope disappeared from her job in a local gift shop on Halloween, 1992. Her car was found abandoned, her keys and purse inside. There were no clues to her whereabouts, so a group of local psychics gathered to seek information that might help locate her. For years, metaphysical types had been drawn to Sedona, becoming neighbors and business owners, part of the community fabric. Locals accepted their skills long before Medium (the TV series based on a Phoenix woman) popularized the notion that folks with paranormal abilities might assist law enforcement.

I still get goosebumps remembering how it felt to be a young woman in Sedona then. As I wrote Over the Edge, that feeling returned—the sense that something unnatural and dark might be following behind me on a forest trail. I could have been David Miller or Marjorie Hope.

No one was able to shed light on Hope’s mysterious disappearance. For months, whispers about Satanists and cult involvement worked their way through town. Then, years later, hikers found her arm bones and skull—pierced by a bullet hole—near a forest road.

Hope’s killer was never found. Perhaps he was a passing visitor. Sometimes, however, evil wears a friendly face.

Sedona has been home to many spiritual communities over the years. As Ryan Driscoll (a Forest Service law enforcement officer in Over the Edge) observes, “One person’s cult is another’s spiritual awakening.” I met followers who were peaceful, polite, and content—if not outright blissful. But some were convinced to give away their life’s savings. Others lost their lives in extreme acts of spiritual initiation—like the woman who perished in July 2003 while hiking up Casner Mountain with a backpack full of rocks and limited water. Or like the three people who didn’t survive the disastrous October 2009 sweat lodge ceremony guided by a charismatic self-help luminary.

Mountain lions aren’t the only predators in Red Rock Country.

Even so, statistically speaking, you’re safer on a forest trail than on a city street. Most crimes on National Forest lands are as mundane as they are infuriating: littering, dumping, graffiti, resource damage or theft. Illegal campsites add a deadlier potential—wildfire.

“Do work that matters in some of the most beautiful places on earth,” reads one Forest Service recruitment message.

But a forest cop’s job isn’t a hike in the park. Chronically underfunded for its changing mission of protecting visitors as well as resources, the Forest Service employs fewer than a thousand LEOs and investigators to cover 190 million acres. Though their ranks are bolstered by cooperation with other local and federal agencies, Forest Service LEOs often work alone in some of the most isolated places in the U.S.

They’ve encountered meth labs and pot grows guarded by weapon-toting cartel members. In some areas, urban-associated crimes make up a significant percentage of USFS incidents. Bootleggers, smugglers, human traffickers, and other criminals have used forest lands to hide out … or to hide victims.

From desert canyons to Arizona’s highest peak, Coconino National Forest stretches over some 1.8 million acres. Travel a few miles from Sedona or Flagstaff, and cell phone coverage is sketchy. Trails and roads are rough and often unmaintained. Nights are dark, and weather can be extreme. Each year forest rangers, LEOs, first responders, and dedicated volunteers save dozens of people.

I wrote Over the Edge for them, and for the ones who couldn’t be saved.

***