“I am sorry that people are so brutal to one another when it takes so little to love one another.”

–model Bani Yelverton

On January 6th, 1970 electronics engineer Jack Froelich returned home to New York City after a two week vacation in Haiti. Coming from that sweltering country to the chill of Manhattan, where it was 20 degrees, must’ve been a shock to the system. At least soon he’d be in the warmth of his apartment. While away Froelich had lent the place to his friend Bani Yelverton, a 35-year-old trail-blazing Black model and jewelry maker who he’d known for six years. As a passing car blasted Diana Ross & the Supremes singing “Someday We’ll Be Together,” the last number one song of the sixties, overhead pigeons soared.

Greeted by the uniformed doorman, Froelich boarded the elevator that soon moved him swiftly to the 11th floor. After opening the front door, a chill hit him. Perhaps there was a window open, he thought, but soon realized that someone had left the balcony door ajar. A few feet away, lying face down in the middle of the living-room floor was Yelverton’s corpse. With the exception of a pair of sheer panties pulled down to her ankles, she was nude. It was determined that her body had been there for nine days.

According to the Amsterdam News, “Her throat had been slashed and there were blood stains on furniture, floors and walls had dried.” Doctor Elliot Gross, associated medical examiner who performed the autopsy, said Yelverton was stabbed in the neck several times before her throat was cut. The murder weapon was also found near the body. “A formidable blood stained knife with a 6-inch blade.” She was also raped, which the tabloids referred to as a “sex crime.”

Court papers stated, “She had also been stabbed in four other places about her neck and head. Red ceramic particles were removed by the police from her scalp and clothing; in the apartment were found two ceramic flower pots, one broken in four pieces.” Lieutenant Walter Stone and Detective Charles Zambri questioned Froelich. “This is terrible,” he muttered. “She was such a wonderful woman.”

2017, forty-eight years after Bani Yelverton’s brutal murder, was the first time I’d heard about her when I was going through the online archives of my late godfather Hans Wolfgang Schwerin. I discovered he had saved various clippings about Yelverton, and I wanted to know more. I asked my mother Frances Gonzales, who had been friends with Uncle Hans, as I called him, from the late 1950s until his death in 1987. “Bani was his friend,” mom replied. “Hans was having a New Years Eve party that year and Bani was supposed to bring the deviled eggs, but she never showed-up. He was upset, but it wasn’t until the following week that he found out what happened.”

Reading the yellowing clips brought to mind other notorious New York City homicides from the 1960s including the Career Girl Murders (1963) and Kitty Genovese (1964). Additionally, I was surprised that I’d never heard of Bani Yelverton before then. Not just because of the ghastly way her life ended, but for the strides she made in her career.

At a time when being a “Negro” model meant segregation and less lucrative assignments, Yelverton was a sensation. At a time when even “Negro” magazines and newspapers used mostly light-skinned women, Yelverton’s brown skin shone through the hypocrisy. However, while the world knows about Black model triumphs made by Donyale Luna, Naomi Sims, Bethann Hardison, Pat Cleveland, Beverly Johnson and Iman, the name Bani Yelverton is practically unknown except by her family, old friends and brittle newspaper articles from fifty-four years ago.

***

Born on March 11, 1932 Barbara Yelverton was a teenager living in Philadelphia in the early 1950s when she decided to leave home and head to New York City. Originally from Savannah, Georgia, her parents Beatrice and Aaron Yelverton moved east to be followers of Father Divine. The minister was the leader of the International Peace Missions and his devotees believed him to be a deity.

Daddy Yelverton later became one of the preachers in Divine’s ministry. “Father Divine created a philosophy that merged elements of Catholicism, Pentecostalism, Methodism, and positive thinking,” stated a PBS article. “Father Divine’s followers believed that he embodied the Second Coming of Jesus Christ…but many in black America thought he was crazy like a fox.”

Surely Yelverton’s folks tried to persuade her to stay, but Barbara’s mind was made up. Somewhere between the city of brotherly love and the wormy Big Apple, she changed her name to Bani and decided to become a model. Two hours later, with nothing but a few dollars and lots of ambition, she arrived in Manhattan. Maybe she stayed with friends, relatives or one of those hotels that catered to single women in the city, but eventually she found her way to Grace Del Marco Agency in Harlem. Founded and owned by glam entrepreneur Ophelia DeVore the agency/charm school was located at 271 West 125th Street and was well-known as a place for young Black women who wanted to model to get their start. Actresses Diahann Carroll and Cicely Tyson, began their careers and later taught there, and that was enough advertisement to get plenty of pretty customers through the door.

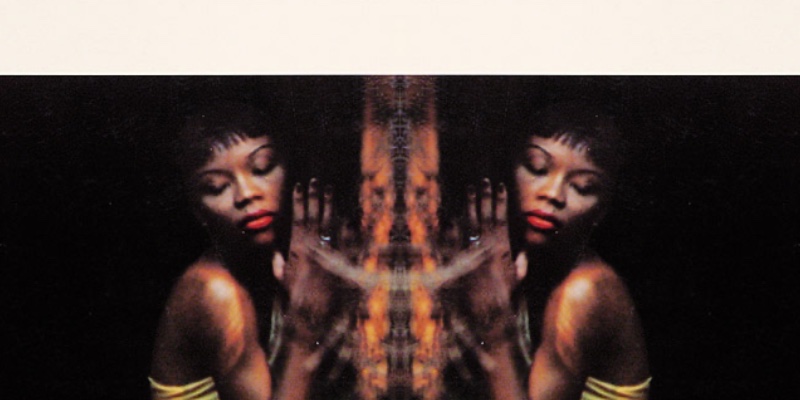

Standing 5’6 in her bare feet, Yelverton had a distinctive brown skinned beauty, “svelte body” and haunting eyes that would later get her inside a few doors. Though mainstream fashion magazines such as Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and Mademoiselle pretended as though white women were their only customers and consumers, Del Marco models were often featured in Ebony and Jet as well as local fashion shows in Harlem. In 1957 Yelverton appeared on the album cover New Orleans Blues recorded by Wilbur De Paris and Jimmy Witherspoon.

Outside the walls of Del Marco, with the civil rights movement beginning to be publicized, it was only a matter of time before there was a better tomorrow for those women. It was the star fashion photographers who were the forward thinkers and wanted to work with Black models. Some might’ve thought that Black women would contribute eroticism to their shoots though others simply believed it was the right thing to do.

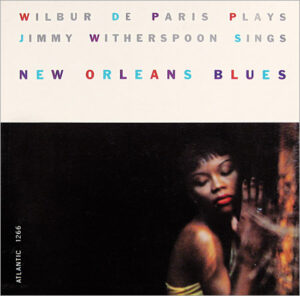

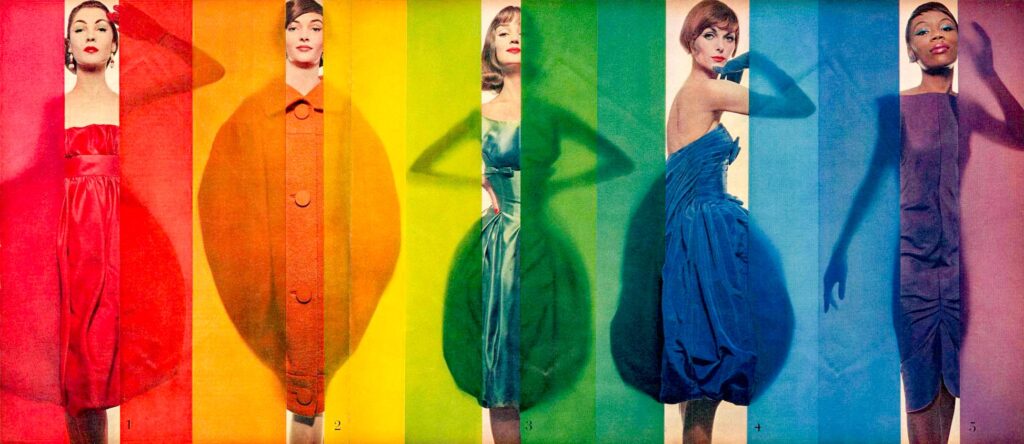

Photographer Erwin Blumenfeld, though not as well known today as contemporaries Richard Avedon and Irving Penn, was one of those guys. A German-Jew who moved to New York City in 1941, Blumenfeld shot for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, but it was his stunning shoot “Rage for Color” for Look magazine in October 15, 1958 that rocked the industry. Much like Life magazine, Look was a publication that relied mostly on photographs and eye-popping graphics.

In Icons of Style: A Century of Fashion Photography by Paul Martineau, he wrote about the spread. “In 1958 Erwin Blumenfeld shot five models standing side by side in rainbow colors for a three-page foldout in Look magazine. The only nonwhite model in the group, Bani Yelverton, was positioned on the far right of the foldout, perhaps so that she could be easily removed by readers who disapproved.” Holding her head high, you could see the intensity and strength in Yelverton’s face that Blumenfeld captured perfectly.

Photo book editor and journalist Miss Rosen says, “For Blumenfeld, commercial photography was a means, not an ends, to continue to experiment, explore, and expand the language of photography beyond the capitalist enterprise that subjugated it in the service of sales and marketing. He was uniquely poised to perceive the radical changes taking place in the United States during the 1950s as the political tides turned from the Red Scare to the Civil Right Movement. Recognizing the conceptual, aesthetic, and political limitations of the mainstream/state media, he continuously pushed the boundaries and reinvented the form, perhaps knowing how we see the world shapes how we think about it.”

The Estate of Erwin Blumenfeld

The Estate of Erwin Blumenfeld

The brief bio of the “nonwhite model,” who was clad in a lavender Trigère dress, read: “Bani Yelverton is a minister’s daughter who models, sells jewelry in Greenwich Village and studies voice.” This was the era before models made millions, but there was speculation that Bani earned $40.00 an hour for that shoot, big money in those days. “Bani’s looks and personality embody the charms, sadness, compassion of a blues singer,” Erwin Blumenfeld said in 1958.

Though he continued to work, on July, 1969 Blumenfeld died by apparent suicide. “In searing heat, the celebrated fashion photographer Erwin Blumenfeld ran up and down the Spanish Steps in Rome in a successful bid—so his family believes—to kill himself,” the Daily Beast reported in 2014. “The 71-year-old had not taken his heart medication, and he suffered a heart attack. He thought he had prostate problems, possibly cancer. By this time Blumenfeld’s career was also in free fall—astonishing, because during the 1940s and ‘50s he was one of the most celebrated and highly paid fashion photographers in the world, creating magazine covers and spreads that were works of art.”

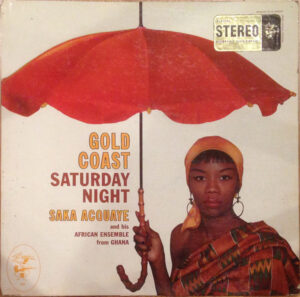

Twenty years later a power move like the Look shoot would’ve been the beginning of bigger things for model Bani Yelverton, but in 1958 the mainstream fashion world was still a hostile environment that imposed its own version of Jim Crow on their industry. The following year Yelverton appeared on the album cover of Gold Coast Saturday Night by Saka Acquaye & His African Ensemble as well as a modeling in the window of a Harlem department store. Under the heading “Most Daring Model of the Month,” New York Age columnist Clyde Reid wrote, “For three days one of the nation’s top sepia models adorned Blumstein’s window on West 125th Street in night demonstrations for a mattress. Incidentally, she looks lovely in bedroom slippers.”

***

Like many young people who came to the big city of dreams with arty intentions, Yelverton had a few other jobs in addition to modeling. Some days she worked as a waitress at the Village Itch located at 518 Hudson Street and other times she was with jeweler/friend Phyllis Sklar, who owned the shop Phyllis Handwrought Jewelry located at 175 West 4th Street. Under Sklar’s guidance she learned how to craft custom jewelry and made a few pieces for friends.

Though she lived in Brooklyn for a while, Yelverton liked to hang-out in Harlem, where she frequented Jock’s and the Red Rooster, and Greenwich Village, where she was a regular at the Rivera, Lion’s Head and Casey’s Bar at 142 West 10th Street. Casey’s bartender Henry Yee considered her a friend and also took Yelverton’s phone messages.

I can imagine her sitting in a bar stool digging the music blasting from the jukebox while talking to people of all races, saying things like, “There is nothing that anyone has to make me envy that person,” or, “I live my life as I please and I harm no one.” Downtown and uptown, Yelverton had a chic clique of friends that included La Ma Ma founder Ellen Stewart, fellow model Dee Simmons, lawyer David Dinkins and comedian-actor Godfrey Cambridge.

Some called her a “Black Holly Golightly,” and much like that fierce character from Truman Capote’s novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s, she had come to New York to reinvent herself and be fabulous. “Bani always said she loved beautiful things and beautiful people,” journalist Cathy Aldridge wrote in the Amsterdam News. Later she described Yelverton as “self motivated, knowing, but always searching.”

Yet, she wasn’t always very revealing about herself and never brought anyone to her apartment. As one acquaintance noted, “She left people where she found them.” Maybe Yelverton didn’t invite people over, because she was ashamed of her neighborhood, the smallness of her apartment or the perception of danger she felt every time she was there.

Yelverton was afraid to go to her own East Village building at 89 East 3rd Street where she had lived on the fourth floor since 1956 and paid $55.00 a month. The community was once a bohemian paradise where many artists, writers, jazz musicians and other oddballs lived.

The Lower East Side neighborhood started changing in the mid-1960s when narcotics and menace took residence. Writer Eric Trules, who was a regular at the infamous jazz club Slugs’ down the street from Yelverton’s building, described the neighborhood as a “dangerous no man’s land of abandoned syringes and skulking, drug-lit dealers and desperados.”

In December, 1970 New York Post reporter Rita Delfiner described Yelverton’s tenement: “The green entrance (wood) door has no handle. Some of the five story walk-ups (on the block) are deserted. Others are gated and the windows are smashed.” The journalist also interviewed friend and neighbor Virginia Thornburg, who was also the building’s super.

“Bani would usually come home only during the day—by taxi,” Thornburg said. “She’d stay long enough to get some clothes, then walk to 1st Avenue and get another cab. There were gangs around here who took dope and they knocked the door down and made noise and she was afraid they’d go up to her apartment.” Thornburg also stated that Yelverton was having work done on her apartment and was hoping to return soon.

Though Yelverton’s fear was rational, it’s still ironic that she was afraid inside the tenement, but would be killed in a luxury building. “Who killed her?” asked one newspaper columnist. “Who dared to break the chain of friendship which bound her to so many diverse people in this city? Was it a man who did it? A woman? A friend or stranger perhaps?”

Two weeks before the alleged killer was arrested, there was a memorial service for Bani Yelverton at Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village. Days before the young woman’s body was cremated, but that didn’t stop hundreds of people from turning out for a last chance to say goodbye to that vibrant woman they loved so much.

***

While Yelverton was house-sitting for Jack Froelich over the Christmas holiday, she allowed friend Robert W. Johnson to stay at her two-room flat. Johnson was the 46-year-old owner of the Village Itch, the restaurant where Yelverton occasionally worked. Johnson had recently separated from his from his wife and had no place to live. In addition, according to police, he was also the last person to see Yelverton alive.

“She had worked at the restaurant on Saturday, December 27 and they left together early in the morning on December 28,” court papers documented. “They shared a cab as far as Sixth Avenue and he continued on to the East Third Street apartment alone; and that, he claimed, was the last time he saw her.” On January, 16, 1970 Johnson was arrested and arraigned for the murder.

“Plaintiff identified a pair of shoes taken from Miss Yelverton’s East Third Street apartment as his,” the court papers continued. “The Medical Examiner had previously examined those shoes and found red ceramic particles in their soles. The Examiner determined that those particles were similar to the particles removed from the scalp of the victim and also similar to the particles removed from the bathroom at the scene of the crime in Washington Square Village.”

Johnson also failed a lie detector test. “We add that plaintiff’s testimony at trial was weak, shabby and totally unconvincing.” A month later the grand jury did not indict him, and on February 17, 1970, the charges against Johnson were dismissed and he was released. He subsequently sued the city. No one else was ever arrested for the murder of Bani Yelverton.

___________________________________

Thanks to my friends Roger Chesley and Keith Roysdon for their help with research.