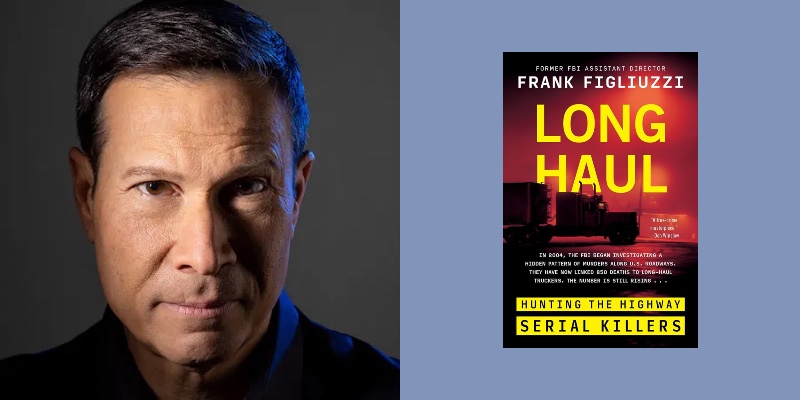

Frank Figliuzzi’s new book contains one of the more alarming pieces of crime data you’ll read this year. Over the last two decades, he writes in Long Haul: Hunting the Highway Serial Killers, the FBI’s Highway Serial Killings Initiative has “compiled a list of an astonishing 850 murders believed to be linked to long-haul truckers.” Though “over the years, multiple truckers had been convicted of serial murders,” about a quarter of the cases in the database remain unsolved. This means that right now, there are “several” active serial killers working as semitruck drivers, says Figliuzzi, himself a longtime FBI agent who was the bureau’s assistant director for counterintelligence when he retired in 2012.

The follow-up to his 2021 bestseller The FBI Way: Inside the Bureau’s Code of Excellence, Figliuzzi’s second book comes at the subject from multiple angles. To understand long-haul trucking, he spent many dozens of hours riding with a long-haul driver, showering at truck stops and napping in the vehicle’s sleeper berth. Meanwhile, he spoke at length to social workers and academics about helping at-risk people avoid human traffickers and pimps, who once haunted rest-stop parking lots but now use the internet for most of their work. And he spent many hours speaking with the crime analysts trying to catch the people—exclusively men, it appears—who commit what the FBI classifies as highway homicides.

Figliuzzi, familiar to many as an MSNBC criminal justice contributor, talked about his book in a recent video interview.

About three years ago, an FBI analyst told you about the Highway Serial Killings Initiative. What was your reaction?

I said, I have no idea what you’re talking about. What is this initiative? And for the next hour, she regaled me about what she does. I was absolutely floored and felt compelled to share this with people. You know, it’s the natural investigator in me, the curiosity—I’ve got to get to the bottom of something.

This is an effort to solve highway homicides, as the FBI describes them. What exactly are those?

The definition is fairly limited. It is female victims last seen at or near rest stops, truck stops or in very close proximity to a highway; who were either assaulted or killed; and who were dumped near a highway. There are hundreds of thousands of murders and rapes within the FBI’s Violent Crime Apprehension Program. But this database only pertains to those very limited cases. I say “limited,” but since its inception in 2003, they’ve identified 850 cases that qualify. And there are at least 200 pending active cases with—and this is staggering—about 450 active suspects.

There are 4 million semi-trailer trucks in the U.S., according to your book, and we should say here, as you do in the book, that it’s a very small percentage of long-haul truckers committing these crimes.

Yes, that’s really, really important. I go out of my way to explain how impressed I was when I rode along for 2,000 miles, and part of my book dedication is to long-haul truckers (“the stalwart American truckers who feed their own families by getting food to our tables and who likely put this book in your hand,” he writes, also dedicating the book to victims, victims’ advocates and investigators.)

So the 200 unsolved cases—the suspicion is that many of are linked to long-haul truckers?

Yes. I double-checked and triple-checked. When I had my conversation with the head of the program, I wanted to make sure that I was not offending a large portion of a critical part of our workforce. I literally said to her, You’re not saying that these are all long-haul truckers, are you? And without blinking, she said, Yes, that is what we’re saying. It makes sense because of the limited definition of how you get into the database. The conclusion is clearly that we have, right now, multiple serial killers responsible for multiple murders on our nation’s highways.

What is the overlap between these crimes, preexisting violent urges that some drivers might have, and the job itself?

It’s kind of a nature or nurture question. A job doesn’t make you a serial killer, of course. I’m not implying that. But there’s something about the isolation of the job, and when I say isolation, I mean weeks or months with very little human contact. That is not good for a person. There’s a Canadian study I cite in the book that that just floored me with regard to health and long-haul truckers. It’s abysmal, as you might imagine, the sedentary lifestyle.

And this maybe worsens the tendencies that lead to these crimes.

Exactly. That personality type—the loner, the misanthrope who doesn’t want people telling him what to do; likes power and control; may lack social skills—is going to find the long-haul trucking lifestyle more attractive. That’s easy to understand. What’s not so easy to understand is what you just said, which is that the job enables and facilitates killing. The isolation and lack of human interaction can exacerbate the desire to kill if—and I want to be careful here—you’ve already got that predisposition.

What do we know about the victims? Most are human-trafficking victims forced into sex work?

My goal here is that this book hopefully can speak for women who can’t speak anymore. The majority of women that fall into this trap are in some form of trafficking scenario. Just as true crime aficionados and crime analysts study the commonalities among killers—serial killers particularly—there are absolutely commonalities within trafficking victims. There’s early trauma; maybe it’s unwanted touching or sexual molestation. There’s early drug use. There’s something really traumatic that happened in the family—divorce, death, suicide. And then there are really bad choices with boyfriends. You can almost see it happening like a slow-moving train.

This has become more difficult for law-enforcement because it’s all taking place online, the pimping, the meetups planned with customers. You might’ve once seen prostitutes offering “dates” in truck stop parking lots, but no more, it seems.

Very, very few. In my road trip, zero that I saw.

Meanwhile, as you say in the book, there’s something like 800,000 private carriers and 4 million semis on the road. So these are really tough cases.

It is truly mindboggling in terms of the investigative work necessary to solve one of these. The killer is exploiting the seams in law-enforcement jurisdiction—he grabs a woman in one jurisdiction, commits the murder or rape in a second and dumps the body in a third. Then in terms of connecting the dots, maybe a local sheriff’s department or state patrol doesn’t have any detectives, or they’ll say, She was grabbed in your jurisdiction, it’s your problem. And then for that FBI database, it’s garbage in, garbage out. Does anybody (with local departments) enter the data? You can’t solve what you don’t know about.

What can be done on the law-enforcement end?

I would implore police departments to enter their data into the database. It works. It solves crimes. And if you really are pressed for time or resources, pick up the phone and call the FBI at your local field office and say, Look, I need help.

At the same time, what is needed is a partnership with the social services, the private sector and humanitarian groups who can come alongside a young woman who’s been trafficked and say, Hey, we’re not arresting you today. What do you need right now to get out of this life right now? And they’ll often say, I’ve got a kid, I need diapers and baby formula. I need rent money.

What about trucking itself? Can it be made less alienating or less attractive to people with violent ideas?

You’ve got to have better vetting. Of course they do a cursory background check, but there are actually trucking companies that prominently advertise that they’re “second-chance companies” for people with felony records. That kind of vetting process should be better legislated.

The idea of only driving a load of Kleenex across the country with no human engagement is problematic. Companies that have multiple types of trucking and trucks should look at cross-training their drivers so that there’s more mental engagement, more engagement with people.

And companies have got to pay more, do more for the health of the drivers. Some guys would secretly tell me that they cheat on their annual required physical. You can go to places on the road where there’s a doctor who will be happy to clear you as fit for duty for $100.

So preventing these crimes is at least partially linked to what the consumer is willing to pay for that Kleenex?

Absolutely. A lot of the things that would help in trucking are costly—extra background checks, extra training, mandated physicals at the corporate facility with a respected physician.

When an ex-FBI employee writes a book, the bureau looks it over before it’s published. What’s that process like? Did you have to take anything out?

It was relatively easy this time around. I’d say it went about three months, which is short. My first book was more like six months. But that was loaded with FBI information.

The only thing that interested me in terms of suggested edits this time was that the woman in charge of the initiative requested an alias. I get it. She felt there was some permanency to a book as opposed to just doing an interview. As I kind of joke in the book, she requested an alias because serial killers tend to be unpleasant.