I’ll never forget my Sunday school teacher telling us that little girls are born into more sin than little boys. I was probably seven or eight. I raised my hand and asked if it was true, and the teacher nodded slowly and sadly, citing Eve, and the Fall. Eve was both Adam’s prize and his ruin, and we needed to remember. Her eyes raked over all of us, but lingered on the girls.

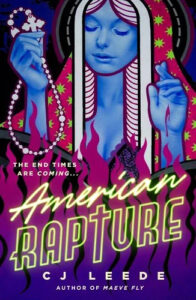

I worked on American Rapture–a horror novel about a good Catholic girl named Sophie navigating her own burgeoning sexuality at the same time as America explodes with a violent sexually-propagating viral epidemic–for a decade. I knew it was a story I wanted to tell of the impossibility of growing up between these contradictions, of being someone who wants to ask that dangerous why, who can’t accept the stories we’re handed down, but is affected by them deeply. The book is obviously set against a much more extreme backdrop than our own. But not in all ways. Much like Sophie’s own internal battle between what she was taught and what she believes, I’m in my thirties, and I still struggle with the guilt and shame taught to us in church.

This is America, so we’re all familiar with the daily double-billboard assault of a LUST DRAGS YOU DOWN TO HELL over the top of a XXX STORE THIS EXIT. Hooters, Viagra ads, Ashley Madison, cellulite removal, surgical med spas. Books banned in schools with the slightest mention of sex or sexual orientation in them. Without fail, someone on tv, or in our lives is discussing acts of sexual violence and implying or even outright saying, Maybe she was dressing too provocatively. Maybe she had it coming. Our country founded by puritans and now fueled by beauty and sex-obsessed capitalism. This impossible tension that fills everything. We tell young girls that their entire value lies in their bodies and ability to attract a partner and procreate, and we also tell them it’s their greatest sin and shame.

My first novel, Maeve Fly (a bit of a wild silly romp with a little sex in it), has been in the world for over a year now. I was out one night, and a friend’s date asked me three times which of the sex scenes in my book were written from personal experience. I’ve received DM’s with insane images (use your imaginations—or don’t) and insinuations of disturbing or mundane sexual acts performed on me in response to the book. And none of this makes me special. None of it is anything compared to what women deal with every day. But the Catholic girl part of me always says in a little voice, But you did talk about sex. Maybe you did bring this on yourself.

Maybe you did have it coming.

In Stephen King’s beloved Carrie—a book primarily centered on sexual shame and repression—Carrie is effectively locked down at home and held in an ignorance that leaves her vastly unprepared for the world and thus wildly vulnerable to it. A young woman coming into her true power around the same time as her body takes on its mature form, and yet still fully at the mercy of those who tell her that same body and power should only be a source of shame. (Will we ever forget the phrase dirty pillows)?

I don’t know what younger generations call each other now, but there was no greater insult when I was young than slut or whore. And at the same time, if we weren’t thought of as the most beautiful, the most appealing, that led to its own despair, its own deep shame that we weren’t desirable enough to be insulted. Always this tension, always this impossibility of existing between desire and purity. The idea that desire is inherently impure.

I sat down here to write an essay on religion and repression in horror. I wanted to talk about religious horror films and books and how women’s roles in them are largely relegated to possession by demons, or as mother vessels to demons or saviors, or as cast-outs or examples for not primarily acting as vessels. I planned to touch on the beauty and ritual of a gothic church, the nostalgic comfort or fear that incense and organ music incite in us. There’s so much to say, and so many sides to all of it, and I don’t have enough space allotted here to get even a fraction of my thoughts out.

But as I’m writing this (during banned books week, and in a time in which our bodily autonomy is a political talking point), and as I’m considering all the ways that we as a society fail young people—all types of folks, certainly not just young girls—, I’m thinking that maybe it’s less about repression in horror, and more about repression as horror. A profoundly important and terrifying truth we put in our books because we are grappling with it, still. All the time.

The idea that a woman dressed up on a night out with her friends, or a woman who writes novels with sex in them, or a young girl just trying to understand her changing body could be seen as asking for unsolicited advances or even violence, could be seen as flaunting something shameful and encouraging an action in response. We build sex up to be something unobtainable or that we’re entitled to or that’s sinful and shameful but also a prize. We fan every flame of desire and want and curiosity, and simultaneously instill a belief that it is dark and base and that there is something wrong with us for wanting it. This most natural of things.

In American Rapture, my protagonist Sophie is as equally unprepared for the world as Carrie, equally sheltered and instilled with shame and a guilt so heavy she will carry it forever, and she stands at the same turning point moment in life. But the antagonists are raised in the same world that Sophie is. The boys who feel they’re entitled to something from her because they too have formed their selves and identities in this hypersexual and simultaneously ultra-repressed tumult, because they too have been taught on some level that the supreme vocation of a woman is to act as a vessel for something else.

When I ask myself why I wrote American Rapture, why I read religious horror or watch it on the screen, when I really stop and think, what do I wish more than anything I had known when I was a young girl trying to step into herself?

It’s this: Repression—religious or otherwise—is the horror. Ignorance is what we should fear. What makes us all ill-equipped for moving through life as humans in natural human bodies.

And maybe little girls aren’t born into more sin than little boys. Maybe sin is just an idea we’ve created for control. A powerful little beast that preys on all of us every day, in and outside of fiction. And maybe it’s one we just don’t need to feed anymore.

***