So here I am, walking down the Champs-Élysées in the midst of 300,000 rowdy strangers, everyone singing the same two songs over and over, one of which is the national anthem, the other is a battle chant, while high above us in the classic Haussmann-style apartments, residents lean out of the windows waving French flags as massive fireworks explode at street level—yes, street level—slightly horrifying—quite deafening—all of which is happening because, as destiny would have it, France just won the World Cup. It’s July 15, 2018, and I don’t even like soccer and I’m dancing around like a drunkard, arm in arm with my new comrades, singing my own incorrect version of someone else’s national anthem. You’d swear World War II has just been won as nearly half a million of my close friends celebrate victory. Everyone’s elated, everyone’s kin, and I, as a bushy-tailed American author, have never seen anything like it.

This is just two months into my move to Paris.

A personal introduction to a new world couldn’t be more disconcerting from an artistic perspective, nor could it be more disruptive to a crime-writing agenda.

I’d come to France to indulge in the old world and type up traditional thrillers in a traditional setting and, within a year and a half, Covid would begin and I’d end up spending my lockdown months in a thirty-three-square-meter apartment with a French woman I barely knew, where every night at 8:00 p.m. she and I would stand on our balcony to clap for grocery clerks and medical staff. I’d head out of that same apartment at 6:00 a.m. each morning to jog—the sun rises insanely early here, the citizens do not—and, in passing precisely zero tourists, zero locals, zero cars, zero anything, I’d have an entire city to myself for two hours per day. Let me repeat that last bit: I’d have the entire city of Paris to myself for two hours—daily—to run past the immaculately empty Tuileries, past the gorgeously empty Louvre, over to the majestic d’Orsay, then finish a loop along the serenity of the Seine, which, for the first time in 9,000 years, flowed untouched by human hands, rendering it a ten-mile-long brushstroke of dark-green steel.

Poetic, perfect, royal. This was my life within a year and a half of arriving.

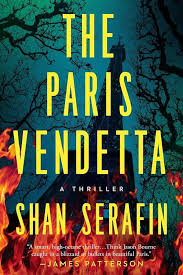

And yet it was in this cultural paradise that I’d ultimately write the most twisted, dark, disturbing, stinging crime thriller of my entire career. I’d typed up a manuscript called The Paris Vendetta, basing it on the machinations of the sex trade, on the insidious way this trade thrives in elegant, elite, power circles, and on the haunting connection between sexuality and violence—the obvious question being how the hell did such a pleasant life in Paris lead me to write something so scathing?

It started with dinner.

I sat down to dine at a one-star restaurant with an old college chum and three of his well-dressed corporate buddies, each hailing from a different corner of Western Europe, each living the type of life where you’re willing and able to pick up a full dinner tab any time you want, any night you want, and ours was two grand. At this table I saw the first hint of something disturbing. These were international business guys and, though I’d done some time behind a finance desk, I’d never known what international business guys were like until this encounter. They travel weekly, not monthly. Every few days is a new nation and every new nation is a blitzkrieg of exploitation. They work hard, play harder, eat dinner until 1:00 a.m., puff on cigars over a postprandial cognac, then begin their nightly outings at 3:00 a.m. Yes, begin at three. Arriving at clubs at three. What struck me most, besides the blinding gleam of their success, was how casually they discussed an active, daily, systemic practice of misogyny.

They traded such polite stories of how lowly they placed women, speaking with little to no reserve. I’d never seen it so flagrantly laid out. America is full of bad behavior but there’s often a verbal denial to it. In the upper echelon of Euro Business—as I was starting to see—gender commodification remained unapologetically overt. I say this in relative terms, as in relative to its own reputation for being starkly progressive. Our banter soon arrived at the topic of prostitution and the reality that they engage in a steady usage of it, which for them, for their industry, was a mark of business strength—the act of paying for pleasure—rather than social ineptitude. What I was recognizing, what I would continue recognizing during the upcoming year, was the pervasive potential for abuse within the high-end corporate world. In fact, after a number of additional encounters similar to that dinner, in what would be a gradual transgression of the degrees of separation—my finding ways to meet more and more the sorts of people I don’t normally meet—I began to inch my way closer to the most insulated perpetrators in the economic equation. Two years into the effort, I got what I wanted and dreaded, my first glimpse of the elite class’s connection to sex traffic, peering through the proverbial keyhole to see. You’d spent your life reading about it, seeing it in films, gasping at it, somewhat doubting its veracity, yet there it stood in front of you. This crime. And you’re stunned.

That dinner was the beginning of my obsession. It launched a years-long exploration, my attempt to fulfill a need to make sense of what shouldn’t make sense. From the onset I was hooked, repulsed, fascinated, aghast—also blithely ignorant of how many barriers would lie between myself and the confirmation I sought. I wanted to expose the inner workings of what was lurking behind a final set of closed doors, yet I could barely access the outer workings of anything. I could only speculate what went on within the back rooms of ultra wealthy individuals, the people who wielded ferocious power, the people who weren’t just above the law; they wrote the law.

Obsessed, I set to work to get myself invited into increasingly exclusive circles. Fortunately, Paris is perfect for infiltration—more so than the US, where social barriers aren’t as dynamic or permeable. What greatly helps in France is that you feel a useful lack of responsibility when wandering around in it. You’re irrelevant here, unbeholden to the whims of their quotidian systems because their systems feel distinctly theirs, not yours. Police cars look cartoonish, money looks cuddly, municipal laws seem cute, and, in fact, nothing feels threatening in your first year abroad because there’s a Disney-ish aura that grants you a false sense of anonymity. You’re constantly not quite anywhere you go, a perennial guest with one foot out of the continent, and, in being anonymous, you’re free to prod and observe humanity without repercussions—so you think—free to abscond with your insights. This is certainly an unhealthy way to regard one’s surroundings but, had I not been duly deluded, I wouldn’t have had the audacity to poke my nose in high places.

Several years and many bizarre nights later, I’d amassed what I’d needed to start my first novel. I’d tracked down enough clues to construct a workable silhouette of an insidiousness lurking behind the facades of Paris and pinned those clues to a bulletin board, strung yarn across the connections, wished I could also add creepy newspaper clippings, or photos of creepy CEOs along with mood lighting—to complete my transition to unshaven detective—stood back, gave it a slow nod, then wrote from page one.

What immediately showed up on paper was not at all the voice I expected. What showed up was a metric ton of my own past experiences, as in my own previous life in the financial sector. It turned out the machinations of modern business were hitting me way too close to home to write with any kind of distance. I’d inadvertently begun to type up what looked like memoirs—highly exaggerated, to be sure—but memoirs all the same—re-creations of certain events, arguments, failures, regrets, certain uncomfortable situations I’d had in working within the corporate monolith. I continued writing, feverishly, crafting what would stand as a beautiful train wreck of wrong intentions. Clearly, I’d failed my two main self-inflicted directives: I hadn’t wanted to write about Paris; I hadn’t wanted to use my personal life. I did both.

A year later the completed manuscript lay on the table as my best step forward in crime fiction. I’d literally walked every route written in this book, visited every neighborhood, entered every building, had many of the exact arguments, and even underwent several of the predicaments. I wrote what I knew. I wrote what felt true. I have no idea how this topic will be received but, without a doubt, if even just a few people get a taste of the deep, dark, diabolical forces simmering beneath the surface of Paris, my journey to the old world will have been worth the price.

***