Six years ago, when I first saw the flier pinned to the wall of the pizza place, near a shambolic shelf of board games, I was skeptical. It held a clip-art silhouette of Sherlock Holmes, with his familiar deerstalker and pipe, and invited any and all to join The Dogs in the Nighttime: a monthly Sherlock group in our small island town in the upper left corner of the country.

Like the detective himself, I’m not much of a joiner, a trait that makes me bad at groups and good at books.

That said, I’ve been a fan of Sherlock ever since listening to Mind’s Eye audio cassettes of his stories on camping trips as a kid. For years, I taught a course in Mystery Literature, and the Arthur Conan Doyle weeks sometimes felt like an exercise in adulation.

Plus, I love people. I love readers. I love mysteries.

Groups: not so much.

My family and I had recently moved to Anacortes, Washington and were excited about the change, but hardly knew a soul. We were grateful to be surrounded by salt water and cedars, and the town was small but didn’t feel small, maybe because of its vibrant library and pair of dreamy bookstores. Libby, my wife, was happy with her new librarian position at the region’s community college and our teens had braced themselves for change—

But moving is never easy, and moving mid-life left us a little bruised. Walking away from a tenured teaching job in order to write induced all manner of midnight panic, as did hearing our kids’ tales of finding no one to sit with at lunch. Although we felt lucky to have found a place to live, our modest new house had cost twice as much as the one we’d left, and needed a ton of work. Our tiny bathroom felt like it was sprouting teenagers. Then came Libby’s breast cancer diagnosis, thankfully caught early, but not early enough to avoid surgery and months of radiation. And, along with the rest of the planet: Covid.

Maybe this minor dogpile had primed me for joining the group. Or maybe it was because the first time I’d climbed the steps to the room above the pizza parlor, I was welcomed by a bright batch of humanity: The Dogs in the Nighttime.

*

There’s nothing fancy about the generic room where we meet, but the old brick building used to house a mortuary—coffins once parked where the pizza now bakes—which seems morbidly fitting. Out the windows, rain falls and seagulls eye our pizza crusts.

The Dogs in the Nighttime was formed in 2011 by Texas-born, marathon-running mystery writer, Kathleen Kaska. Worldwide, there may be hundreds of such groups, many with allusive names that are as clever as cozy titles: The Stormy Petrels, The Giant Rats of Sumatra, Mrs. Hudson’s Lodgers. They range from the scholarly and ceremonial to book clubs that meet in bars and libraries. Some of the stauncher groups read the canon in order of publication, in order to trace the development of characters and gauge Conan Doyle’s evolution as a writer. The pinnacle of these is also the oldest: the Baker Street Irregulars, founded in 1934. The few B.S.I. members I’ve met are dapper, affable, and astounding in their knowledge. They’d kill us on trivia night.

B.S.I. membership is invite-only, but no one needs an invite to be a Dog. This is not to say that we don’t take the stories seriously, but we also read pastiches—Sherlock spin-offs—as well as the occasional Poe story. And we host an original radio play at the library, complete with whimsical sound effects and baffling British accents.

We pride ourselves in being a motley bunch. In addition to several mystery writers, members include chemists, film buffs, medical professionals, Sherlockian scholars, and avid readers. Among us are several married couples, a pair of sisters who are never far from a cruise ship, a bright-eyed Scotswoman, and a retired detective named Holmes with a dog named Watson (really).

Besides being fans of a good story, we gather for different, overlapping reasons: to take a journey into Victorian England. To experience justice in an unjust world. For the interplay of art and logic. And for Sherlock’s ferocious curiosity, a trait we mimic each time that we gather. The fact that his knowledge runs more deep than wide—more esoteric than encyclopedic—seems like an accurate reflection of our collective brain. None of us are geniuses, but together, we cover a lot of ground.

For me, the appeal has always been the darker side of the stories: the spooky settings, the moody prose, and the sense that in Sherlock’s cocaine habit and opium dens, we glimpse the spectrum of humanity: a person who knows pain, yet finds solace in his pursuit of knowledge and art. Like many literary detectives who have followed him, he’s waded through “deep waters” and come out the other side to serve a higher purpose.

It’s probably good that politics are verboten in our meetings, a norm that’s not always easy to follow. The proverbial gramophone has skipped a few times, and some of our feet could be heard dragging up the steps in the wake of the recent election—but for the most part, we embrace civility. We generally agree that there’s something amusing, and sometimes sexist, in the way Conan Doyle describes the damsels of these stories. And we can discuss Watson’s enthusiastic embrace of the Crown, while also pointing out his blind spots, such as the lasting scars of colonialism.

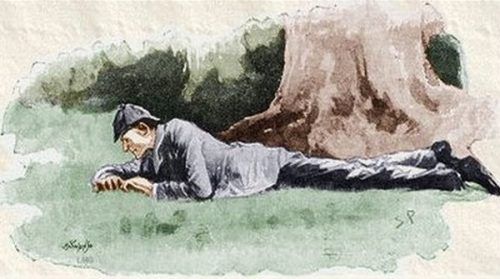

At times, we dig so deeply into these stories that it feels like we are in a Richard Osman novel, trying to solve something that is just beyond our grasp. One member observed that when she sees us drilling down into the text, she is reminded of “Holmes, prone on the grass with a magnifying glass.” The way we discuss him sometimes, you’d think he was a family member who’d just left the room, pipe smoke lingering.

*

Reading can be full of contradictions. It is typically a solitary act, ideal for the non-joiners among us. Yet through reading, we can also learn to empathize and grow closer to each other.

There is a similar irony in the fact that we gather to focus on Sherlock, of all characters. He is sometimes diagnosed by today’s standards as having Autism Spectrum Disorder, being Bi-polar or, in the Benedict Cumberbatch interpretation, “a high-functioning sociopath.” In any case, he struggles to be tolerant of mortals such as Watson—and, by extension, us.

In his own way, though, even Sherlock was a joiner. His association with the Baker Street Irregulars—a group of street boys whom he occasionally calls upon—adds color to a number of stories. And through his brother, Mycroft, he was affiliated with the Diogenes Club, a group of “unsociable” men in London who, “some from shyness, some from misanthropy, have no wish for the company of their fellows.” Unless they were in a special room, its members sat in silence, forbidden to speak or take notice of each other—yet they gathered all the same.

Sherlock even says that the club has “a very soothing atmosphere.”

Further proof that, whether it comes naturally or not, we can all find our place.

“For a long time he remained there…”

(Illustration of the Sherlock Holmes short story, “The Boscombe Valley Mystery,” which appeared in The Strand Magazine in October, 1891.)

Works Cited

“A Study in Pink.” Sherlock, season 1, episode 1, BBC, 2010.

Conan Doyle, Arthur. “The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter.” The Memoirs of Sherlock

Holmes, 1893, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/834/834-h/834-h.htm.

—. “The Adventure of the Speckled Band.” Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, 1892, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1661/1661-h/1661-h.htm#chap08.