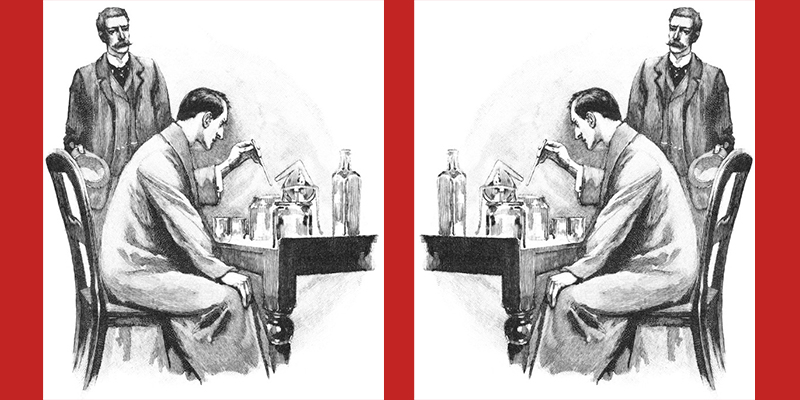

When Sherlock Holmes is first introduced, towards the beginning of his inaugural novel A Study in Scarlet in 1887, he is presented as a scientist before he is presented as anything else, including as a detective. Specifically, he is introduced as a chemist. In his first appearance, he is puttering around a laboratory filled with Bunsen burners and test tubes, gleefully informing the entrants (Watson, who is yet a stranger, and their mutual friend Stamford) that he has just discovered a reagent that can cause diluted hemoglobin to precipitate out of solutions. This is technically the first mystery in the Sherlock Holmes canon: a medical conundrum.

Moments before Watson and Stamford enter, Stamford takes Watson aside to warn him about Holmes’s temperament (a piece of advice intended to influence Watson’s decision to become Holmes’s roommate or not—the question that leads him to meet Holmes in the first place). Stamford informs Watson that Holmes is “a little too scientific,” implying that his empirical, technical academic interests are so consuming that they bleed into his personality, making him more rational than sensitive and more calculating than empathetic (and at the very least, potentially making him a vexing flat-mate). Holmes’s scientific work is so consuming that it has even altered his skin—when he goes to shake Watson’s hand, Watson notes how it is “was all mottled over with similar pieces of plaster, and discoloured [sic] with strong acids.”

Thus, of all the different qualities Holmes will be revealed to embody, he is first presented as “science” incarnate. Although “A Scandal in Bohemia” is the first story which expanded on Holmes’s performative methodology, the opening paragraph also stressed Holmes’s scientific essence, referring to him more as a scientific apparatus than a man: “the most perfect reasoning and observing machine that the world has seen.” A few lines later, Watson seems to be describing him as a microscope in human form, calling him “a sensitive instrument” with “high-power lenses.” This characterization—of a Holmes with fine-tuned lenses instead of eyes—sets up the relationship between Holmes’s scientific work and his reliance on the visual (as undertaken through performance) in the development of his crime-solving discipline.

Holmes’s inherent scientific nature is not a quality that diminishes in the character as the stories progress. Holmes was constructed with the specific purpose of being a scientific savant, above all else—and an embodiment of visual diagnostic skill.