Those of us who write series novels generally spend a lot of time thinking about our characters’ background—where do they come from, what is their education, their taste in food and music, what jobs have they held? Some writers work out entire biographies of the characters, filled with details that may never make it into a story, but that feel necessary for their creator to know. How can our characters be vivid, we wonder, how can they move and talk and appear in three dimensions, if there are parts of their history that even their author doesn’t know?

Thirty years ago, I published The Beekeeper’s Apprentice, the first episode in what became the Mary Russell & Sherlock Holmes series. Russell is a girl of fifteen when we first meet her, and throughout the course of the story, we learn (I learned) about where Russell came from and how she happened to be in Sussex. We hear of her family tragedy, her various relatives, her Jewishness, her academic life at Oxford and the friends she makes there—and that’s just the first book in a series that is currently hitting the #18 mark.

Not all crime stories weave in the more peripheral information about the people on the pages. The traditional mystery does encourage a more thorough exploration of background, but the faster the pace, the fewer opportunities to pause and chat to the reader about childhood homes and favorite pets. Still, even a thriller writer like Lee Child takes the occasional detour into Jack Reacher’s brother, his army buddies, his past experiences.

And then there’s Arthur Conan Doyle.

Sherlock Holmes is arguably the best known character in crime fiction. The silhouette of a man with a big pipe and a deerstalker on his head (both post-Doylean details, by the way) is instantly recognized anywhere in the world. Doyle’s “Sherlockisms”—those pithy phrases such as the lack of activity from a dog in the night-time, or “Elementary, my dear Watson” (which, again, is not found in the original stories)—are used even by people who have never read a Conan Doyle story.

And yet, when you go looking for actual life details about this vivid and universally-known character, searching for hints as to his experiences and history outside of those directly seen by Dr. Watson, one needs more than a magnifying glass and a dog with a sensitive nose.

I know. I write Holmes as a character, and it’s startling how much I’ve had to make up.

When I first began to write the Russell “memoirs” (primarily from Mary Russell’s point of view) and realized it had been too long since I read the Sherlock Holmes stories to trust my memory, I—being the trained academic I was at the time—went out to do my research. Fifty-six short stories and four novels, surely that will give me plenty of detail, right?

Wrong.

Oh, yes, Dr. Watson gives us tidbits about their life in Baker Street: the odd skills Holmes uses in solving crimes, his physical characteristics, his habits and violin playing and drug use and his attitudes towards women, Americans, and policemen. We even catch glimpses of the detective’s taste in music and cuisine. But when it comes to the insights one might expect from close friends, those comfortable revelations about Holmes’ family and home life in the years before he and Watson met in the St Barts laboratory, the clues are as thin on the ground as if Holmes were a man in witness protection.

And the things we do learn tend to introduce more questions than they answer:

–Holmes is from a family of “country squires.” (From where? Were they titled aristocrats, or simply commoners with money? Why is he now so distant from them?)

–He has an older brother, Mycroft, who is something powerful and mysterious in the British government. (Indeed, Holmes says ominously, at times Mycroft is the British government. Does that mean he’s a spymaster? An extortionist? A Victorian Rupert Murdoch?)

–His grandmother was “a sister of the artist Vernet,” who brought into the Holmes family “art in the blood”—that ability of artists to take note of the telling detail. (But, which of the many Vernets does he mean?)

–He went to university (Oxford? Cambridge? Did he graduate, and if so, in what subject?)

And these facts are about all we get. A university friend of Holmes is mentioned, but only in the context of a case the friend brings him. Neither does he explain how he came to know their extraordinarily—bizarrely, even—patient and forgiving landlady, Mrs. Hudson. What self-respecting landlady would put up with a tenant who shoots holes in the walls when he’s bored and fills his rooms with street urchins and criminals?

This lack of personal detail is hardly Watson’s fault. The two men shared rooms in Baker Street for half a dozen years, embarking on countless investigations together (some of them putting Dr. Watson into personal danger) before Holmes thought to mention that he had a brother—and then, he only did so when said brother was about to appear on their doorstep.

As a writer, I find it fascinating how thoroughly we know this great detective when so much about him is a complete enigma. Perhaps the modern preference for back-story gets in the way of creating a vivid sketch. Perhaps a closed book is all the more intriguing for being unread. Why do we need to know whether Sherlock Holmes’ father held a minor title, or which Oxbridge university he went to, or whether there was another brother—or half a dozen sisters with a gaggle of children who adored their weird uncle Sherlock?

One thing the lack of detail creates is an itch to fill in the holes. No other fictional character has inspired such an industry of pastiches, one that began while Conan Doyle was still producing the originals. Sometimes these are tales briefly mentioned in the originals that cry out to be told, such as that of the giant rat of Sumatra (from “The Sussex Vampire”) or the mystery of the repulsive red leech (“The Golden Pince-Nez.”)

Other times, writers burrow past the teasing subject of untold stories to the larger mystery of Sherlock Holmes himself.

Writers like me.

My first few Russell & Holmes novels found Holmes firmly in the role of supporting actor, with the focus on the development of young Mary Russell from adolescent to young woman. But at a certain point, I found myself eyeing Holmes, and wondering just how he would have developed, under the influence of this unexpected apprentice-turned-partner. Over the next few books, he began to move beyond where Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories left him, a solitary figure with little but his bees to keep him company. He grows, he reveals himself—to Russell and to us—as we come to know more about Mycroft, and that family of country squires, and even meet a son that he did not even suspect until the boy was in his twenties.

Finally, I decided that it was time for those Vernets. Time to explore how the artistic impulse got into the Holmes brothers’ blood. Nothing simple, obviously—could anything about Sherlock Holmes be other than extraordinary? And perhaps some of it was information that Holmes himself didn’t know? Episodes and influences that reached far back into his life, and shaped the man he became…

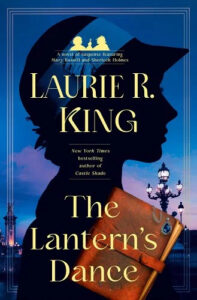

Time to open the pages of this notoriously closed book, Sherlock Holmes, with The Lantern’s Dance.

***