David Joy is the author of the novels The Weight Of This World, The Line That Held Us, When These Mountains Burn, and Where All Light Tends to Go, which will be made into a film directed by Ben Young, starring Billy Bob Thornton and Robin Wright.

This installment of Shop Talk ventures well off the beaten path. That makes a lot of sense, considering David lives way up in the mountains of North Carolina. So far out, he had to drive twenty miles just to call me via Zoom. He’d also gotten tied up with some ducks the day before, which seems like the perfect spot to kick this thing off.

Eli Cranor: Tell me about these ducks?

David Joy: There’s a guy had a bunch of these Peking ducks he didn’t want. When folks don’t want animals around here, I take them. Usually, it’s roosters. People get chickens, and a couple turn out to be roosters . . . Well, that’s how they end up in my freezer.

EC: Damn, what a way to start an interview. I’ve been a fan of yours for a while now, and I remember one time reading where you compared writing a first draft to going out and digging up clay.

DJ: My mother was a potter. All my life I was around that. The first draft, that’s the hard part. That’s going out and digging clay. Revision is where you finally get to chuck that son of a bitch on the wheel and make something. I love revision. The further I get into this process, the more I realize every book’s going to be different. My process early on isn’t my process now. You either adapt to that, or you fail. The thing that remains is that fact that once the clay’s there, the clay’s there.

EC: I love that. You mentioned how your process has changed over the years. Can you dig deeper into that?

DJ: The first novel I ever wrote, I was working two jobs. Usually got home between ten and ten thirty. I’d shovel food in until eleven and then write until three in the morning. Then I’d get up and do it again, until the book was done. I wrote that whole first draft in a month and a half. Really out of necessity. That was the only time I could find. I had a story I was compelled to tell. So that’s what I did. Then, when the second book came, I was under contract for it. That was different.

EC: That first book, that was Where All Light Tends To Go?

DJ: Yeah, so when that second novel came around, I was under contract, which changed things. One thing that did remain the same was that I worked at night. When I was in the middle of that novel, The Weight of This World, I didn’t come out during the daytime. Period. That’s a really dark novel. I can remember talking with my sister afterward, and I told her it’d take a very long time to find my way out of the darkness I’d created.

EC: And how’d your process progress from there?

DJ: For The Line That Held Us, I was living with my girlfriend. I had a dog, the dog that’s sitting beside me right now.

EC: Things were looking up, right? It wasn’t so dark anymore.

DJ: Yeah, I guess. But the thing that really changed was that I couldn’t write all night and still have a relationship. So I wrote that novel during the day. Things just kept changing. This novel I’m working on now, it refuses to be written linearly. That was a fucking nightmare. The way that I’ve always written has been coming to know characters, and once I know them intimately, I can throw them into any situation and I know what they’re going to do. For this novel, I couldn’t do it that way. It’s been a lot more like having all these puzzle pieces spread out on a table. Maybe you can work on a corner section a little while, but then you got to work on this section in the middle. Eventually all those blank spots start filling in.

EC: The puzzle metaphor reminds me of my talk with Steph Cha. How did you tackle writing these different, non-linear scenes? Like, did you just start writing whatever scenes popped into your head?

DJ: The longer I sat with these pieces of the story, the more I knew. I think I had to learn the whole story first in order to make the central mystery work. If you think about a writer like Laura Lippman, she’s surgical about where things fall over the course of a narrative. Those little acts of discovery have to be planned out like that. I don’t think you could write a book like she writes just going straight through like I’ve always done. This latest book’s been incredibly different. I can tell you flat out I don’t like it. I don’t like working that way.

EC: What sort of planning do you do prior to drafting? Do you outline?

DJ: I never have, and I didn’t with this. But the one thing that has stayed true through every book I’ve written is that I tend to start with a single image. It doesn’t have to be a completely still image. It could be a fragment of a scene. But I can see people there. It’s always been a matter of trying to figure out who those people are, where they’re coming from, and where they’re going. I’ve been working on this novel I’m working on now for going on five years. Eventually, what happens is you get to know these characters so well it’d be like if I was describing a scene in a grocery store, and I inserted your mother into that scene and I said, “Eli, what would your mom say?” You’d know exactly what she’d say, because you know your mother that way.

EC: How much have the authors you admire influenced your process? I mean, you’ve probably talked craft with Ron Rash, right?

DJ: Ron is undoubtedly the biggest influence on me. I don’t necessarily even mean that as much as his work, as I mean the man. He was a mentor, a damn good friend for me. I’ve talked about all kinds of things through the years with him. Early on, I can was trying to mimic Daniel Woodrell. I can remember the first time I ever read Tomato Red. I read that book over and over for probably six months. There were entire days where I didn’t read anything but the first chapter, over and over. I’d get to the last word of that chapter and realize I hadn’t even taken a breath. I knew the minute I read it, that that’s what I wanted my prose to do. That ability to have my foot on the pedal and mash the fuck out of it—that’s very much rooted in Daniel Woodrell. Ron Rash was a huge friend and mentor like I already mentioned. One of the ways he helped me most was by handing me books. The first time he gave me William Gay’s I Hate to See That Evening Sun Go Down, that was when I realized you could write a story about those people—my people—and that you could do it that well. At heart, Ron’s a poet, and a short story writer. Most people know him for his novels, but I would argue the short story is his form. It’s Ron’s attention to the line, the rhythm the meter—that was his biggest influence on me. I love just sitting with sentences and trying to get the meter right. You can force a reader into a rhythm whether they know it or not.

EC: How do you go about trying to sharpen your lines? I’m guessing it doesn’t come early. Sticking with the pottery metaphor, you’ve got to get a hunk of clay on the wheel before you can start making it pretty, right?

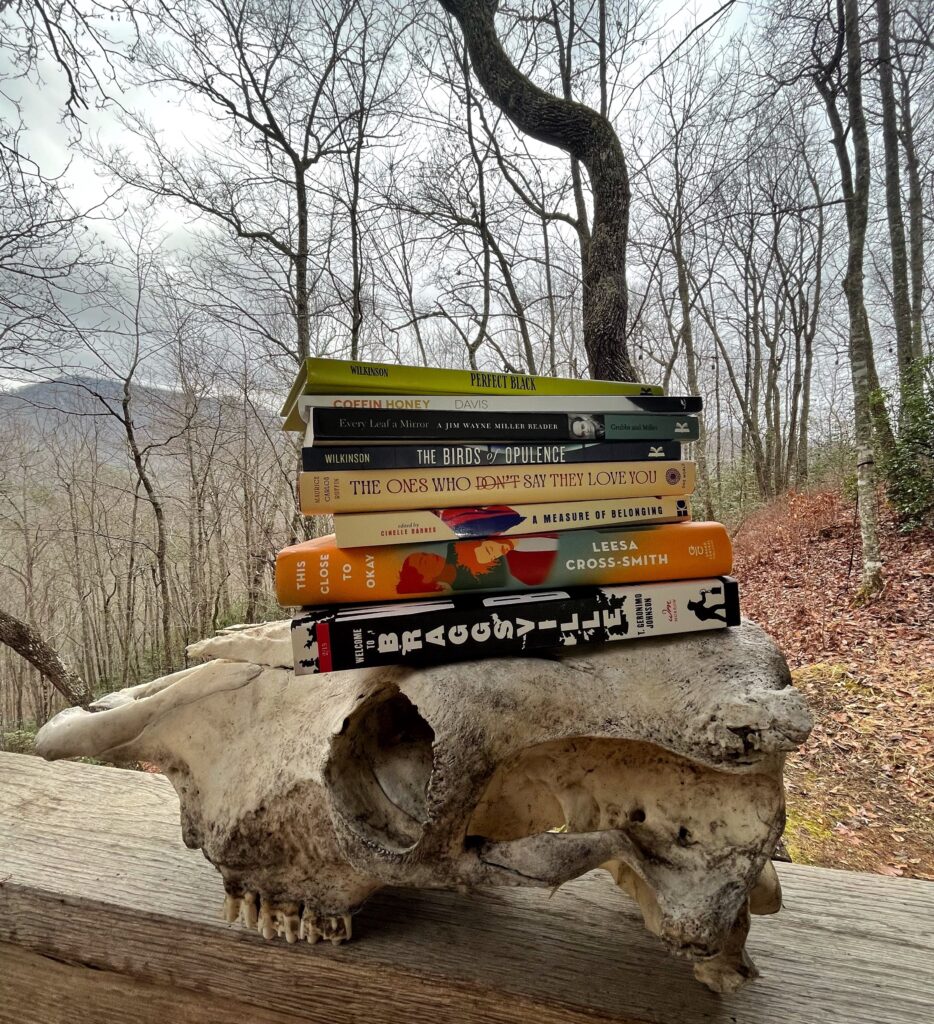

DJ: Yeah, but it comes even before that. I read more poetry than I read fiction. It starts with the reading. Writers like Crystal Wilkinson, or a poet like Ray McManus. Getting those people in your head helps.

EC: How do you compose? Do you type straight into a computer? Do you have an office? Anything like that?

DJ: I’ve never had an office. For the most part, the only place I’ve ever had to work’s just been sitting on the couch. I’ve never written longhand, either. It’s not that I don’t enjoy it. It’s that I edit so heavily, even as I’m working. By the end of the day, I’d just have a fucking page with everything marked out. I have to work on a computer. I’m typically not happy with a day of writing unless I’ve had an initial read and feel good with how it sounds. When I’m really going—when I’m in “that paddlewheel of days,” that’s what John Ashbery called it, you know, when one day just turns into the next—what I really like to do is at least have a couple lines into the next scene. That makes the next day a hell of a lot easier.

Photo courtesy David Joy

Photo courtesy David Joy

EC: You mentioned you’ve been working on this current manuscript for going on five years now. I’m guessing that process has had a lot of stops and starts. How hard is it to get back into the story once you’ve dipped out for a while?

DJ: I’ll be absolutely honest—this is the hardest book I’ve ever written. I’ve already got plans for what I’m doing next, and I’m writing pure fucking gasoline. I’m gonna mash that pedal and run it till it’s empty. I think I’d get a whole lot of enjoyment out of that after this book.

EC: When you’re drafting, do you aim for a daily wordcount?

DJ: Never cared for wordcount. Never really paid attention to anything other than whether or not the story’s moving forward. When I say that, it can be something as simple as figuring out another aspect of a character. Doesn’t even have to be words on a page. The story’s progress is the only gauge I’ve ever used. The hard part is when everything goes blank for a while.

EC: What do you do when that happens? Do you take time off?

DJ: Hell yeah. Listen, the sponge is going to dry. That’s inevitable. You can’t fight that. You have to go find another source of water. For me, what that looks like is reading and spending more time in the woods than with people. The wheels are turning in a way that’s one stage removed. I’m not literally trying to think about the story. I’m thinking about squirrel hunting, frog gigging, running traps, or whatever. But the whole time, in the background, the book’s just sitting there stewing. Eventually, it comes to the surface and sets you loose again.

EC: What are your thoughts on writer’s block?

DJ: The idea of writer’s block is something that terrifies young writers. The only way to ever get past that is to come to trust your own process. I know for a fact that the story will come back. So I don’t fear when it goes away. I trust in my process enough to know that I’m going to write. It’s the only thing I know how to do. I’m compelled to tell stories. That’s it. It’s really a compulsion. I’d feel like I’d die if I didn’t get these stories out of me. I know you know Ace Atkins, so you can ask him about this. There have been times when I’ve had to step away from a story and I was so scared of dying and that story going unfinished, that I’d send him the manuscript. I’d say, “Ace, if I fucking die, you have to finish this.” I sent it to him, because I know he could finish it. Ace is a fucking chameleon. He could pick right up on what I was doing and he could finish it, and finish it well. But that’s how important it was to me. I felt like it had to be finished. The idea of a story ever going unfinished. That’s scary to me. That’s a whole lot scarier than the gaps.

EC: While you’re working, do use anything to get you in the right mind. Music? Bourbon? Anything like that?

DJ: Not really. With my first novel, I woke up from a dream and I could hear Jacob McNeely talking. It was just a matter of keeping up. But there was a song that accompanied that character. It was Townes Van Zandt’s “Rex’s Blues.” That song was an entry point, especially when I’d step away for a minute. That’s the only novel that’s ever worked that way. I need utter silence. I live in an eight-hundred-square-foot house. Four hundred on top of four hundred. Basically, two rooms. So when my girlfriend’s up above me, the minute she steps out of bed, the spell is broken. Like, I’m not in this world, I’m in another fucking world. When the fiction is going well, that’s what it feels like. When I’m walking around Walmart it feels like I’m in a dream.

EC: Amen to that.

DJ: Seriously, for me it’s a matter of trying to have that spell cast and remain in that space as long as I can without any interruptions. Music would be an interruption. Even something as simple as a window wouldn’t work. I don’t want to look outside.

EC: Are you the same when it comes to revisions?

DJ: Revision looks different. I mean, I’ll drink beer and revise. You can draft sober and edit drunk.

EC: Hemingway’s rolling over in his grave. Take me through your revision process. What does it look like?

DJ: My first draft tends to be fairly clean, as far as narrative structure’s concerned. For me, it becomes a matter of honing the damn language. I was very fortunate early on to have a brilliant editor. She was able to see things I wasn’t able to see. When I first turned in The Line That Held Us, she told me straight up it wasn’t any fucking good. A shitty editor would’ve just taken what I sent her and put it out. That’s how shitty books get made. There are plenty of shitty books, and there’s new ones every Tuesday. But listen, it took her saying that for me to get the book that we ended up with. That relationship is so damn important, especially publishing at that level. It’s a real blessing to develop that sort of relationship, and it takes time to get there. If some Joe Blow is my editor and he tells me my book sucks, he may very well be right, but I can tell you what my instinct’s going to be. It’ll be, “Fuck you.” Even with a good editor, that’s still my gut reaction.

EC: It takes me at least twenty-four hours to come to terms with an editorial letter.

DJ: That’s how it always works, man. I mean, hell, you wouldn’t have sent it to them if you didn’t think it was right. But then, when I look back on the changes she made, I know she was right from the start. The truth is, that that sort of relationship is dying in this industry. For a lot of writers, there’s no editorial insight, and that’s a shame.

EC: Do you print off your pages for revision?

DJ: Yeah, I used to when I was just starting out. I just work straight through on the computer now. I don’t know what changed, but I do know I’ve burned a lot of those printed-out pages. The first time I ever just burned a ton of pages, it was twenty thousand words. The next time it was like forty thousand words. Then it was a whole fucking novel. With every single one of them, I printed out those words, had it in hand and I quite literarily set it on fire. I also erased the file on my computer. It didn’t exist anymore. The reason for that was very much rooted in Harry Crews. It’s the idea that the nonwriter reaches a point where he realizes he fucked up, but he’s so scared of starting over, he forces the book forward anyway. The writer puts it to the fire.

EC: I’ve never heard that Harry Crews bit, but it’s spot on.

DJ: I mean, hell. You’re gonna fail. If you want to take it all the way back to that pottery metaphor, they don’t all make it out of the kiln. Some come out and they’re fucked up. What are you going to do? You throw it away and you start over.

EC: You’re right, but that damn sure doesn’t make it any easier. This has been great, man. We’ve ventured off the beaten path. You got anything else you want to add?

DJ: Yeah, listen. I hate talking about craft. I especially hate craft talk on Twitter. There’s a lot of people, that’s the only thing they talk about on there. It’s like you’ve just followed a bunch of accountants and the only thing they tweet about is fucking accounting. That’d bore me to tears. For a long time, I kept looking for advice, especially early on. Then I was fortunate enough to find a Raymond Carver interview in the Paris Review. There were a ton of things he said in there that were me to a tee. I mean, I’d come from watching Ron Rash work, and watching Ron Rash work is like watching a goddamn machine. He’d have him a glass of sweet tea and he’d write every fucking day. I remember he had writers block, and it lasted for about twenty-four hours. I’ve never been that way. Then I read that Carver interview. Carver said when he’s not writing, it felt like he’d never written a single word in his life. That’s me. He’s the one that mentions that John Ashbery idea, “the paddlewheel of days.” I get that. But a lot of people, they tend to look at process as an equation. If they can plug the variables into the proper equation, then they’ll get a fucking book. The truth is that if you’re looking at it like that, you’ll never get it done.

EC: That’s right. Craft isn’t an equation, it’s a process, right?

DJ: I think so. I think that’s closer. Maybe you listen to all this I’m saying, and something helps you. Or maybe you listen and you think, David Joy’s full of shit, I don’t work that way. Honestly, I’d hope that would be the case. I’d hope Eli, as a writer, is so steadfast in his process he recognizes what works for him. There are no fucking answers. What may work today might be gone tomorrow. That shit is fluid. The only requirement is the compulsion to create. Outside of that, there is no other answer.