Lou Berney is one of the reasons I write crime fiction.

Coming up, I cut my teeth on Southern writers like Flannery O’Connor, Larry Brown, Harry Crews, and Jesmyn Ward. It wasn’t until I found The Long and Faraway Gone, Lou’s third novel, that I realized the full power of crime fiction.

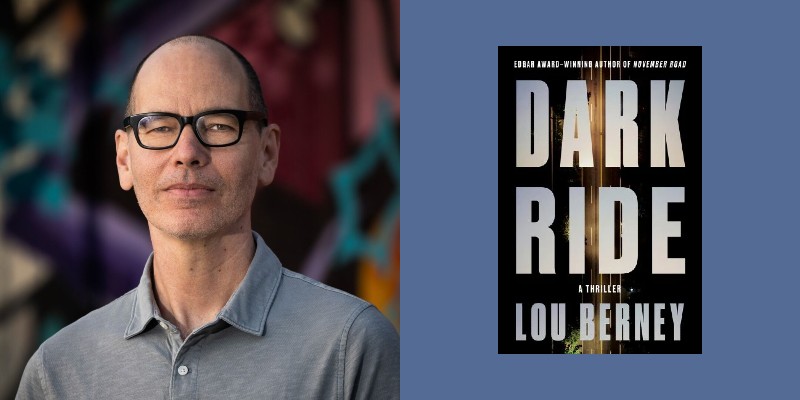

I’m not alone in my admiration. Lou’s work has won the Edgar, Hammett, Steel Dagger, Barry, Macavity, Lefty, and Anthony awards, and he has been a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize twice.

Lou just dropped his fifth novel, Dark Ride, last month. It’s on my nightstand, but I haven’t been able to crack it just yet. I did, however, have the pleasure of talking shop with one of my literary heroes.

So, without further ado, here’s Lou . . .

Eli Cranor: Huge fan of yours, man. So stoked to do this talk, but even more excited that there’s a new Lou Berney novel out. How long has it been since November Road?

Lou Berney: It came out in five years ago. So, yeah. It’s been a while.

EC: And what was the space between November Road and The Long and Far Away Gone?

LB: Three years.

EC: Is the time in between by design? Like, do you have any schedule in your mind of when you’d like to get another book out?

LB: I try to get the next book out as soon as possible. The last couple times around, I’ve run the car off the road. That’s been the delay. In my defense, I did write a book between November Road and The Long and Faraway Gone that’ll come out eventually. It’s the third book in my series and it just hasn’t been published yet. This last one, Dark Ride, actually only took me about a year and a half to write. I was under some pretty extreme pressure. I felt like I was letting my publisher down, letting everybody down. It was tough. Sometimes things work and sometimes they don’t. You have to know when to pull the trigger and move on.

EC: What do you do when you get your first spark of an idea?

LB: This is something I think about a lot. It’s something I teach too. First thing I’ll say is I think every writer’s completely different. Every writer is gonna have a different process. Anybody who tells you that you should do something a certain way—run away and don’t listen to that person. When I get an idea, I take a Moleskin notebook and a pen and I go on the couch. That’s it, my routine, and I just sort of do a lot of jotting down of random ideas, possible threads, whatever. There’s no pressure. You’re not in front of the laptop. You’re not having to write a sentence. You’re just having fun with it and seeing what could happen.

EC: How long do you stay in that mode?

LB: Maybe a month or two. Maybe not that long. I’m usually chomping at the bit to get to the next stage, which is when I map things out.

EC: So this map you make . . . Is it like a full-on outline?

LB: I like to stay away from o-word because that always brings up the image of Roman numeral one, letter A . . . I hate that kind of formality. I use Scrivener to try and get my head in that space. I’m just making shit up, you know? Moving things around, but in a way that’s not gonna cost me months if I get it wrong. Is that kind of how you do it?

EC: More so now than early on. At first, I just started writing as soon as I got an idea. And when I missed the mark, it definitely cost me months. Years sometimes. So now I brainstorm in a notebook like you mentioned.

LB: Scrivener is great because it keeps me from getting overwhelmed. It has all these tools I don’t use, but it has this one tool that is really nice where you can kind of collapse and expand things. I don’t use it to write, though. I just use it to plan stuff out. I write straight into a Word doc. It’s so tricky, man. There are times when it’s best to really think your way through it, and there’s times when it’s best when you don’t know where you’re going. There’s no one recipe.

EC: So, Moleskin for brainstorm, Scrivener for planning, then Word for drafting. That’s a new one. Can you explain how decided on those different approaches for each stage?

LB: I don’t know, man. It’s probably something to do with the neurochemicals in my brain. I’m tricking my brain into shifting gears, I think. I was a baseball player and, you know, baseball players are stupid superstitious. Every time you go to the plate, you do the exact same thing. You tap your bat in the exact same spot or whatever. That’s how this all works for me. Each new tool puts me into a different mode of thinking, kind of like like tapping the bat. Maybe it’s something like that. I don’t know.

EC: What did writers do before we had all this software?

LB: Well, I’m an old dude. I remember writing before there were computers. I wrote my first collection of stories on a typewriter. I think that might have screwed me up a little bit. I’m more focused on the line than I’d like to be. I’m happiest as a writer when I’m a storyteller. I can very easily spend too much time making a beautiful line. I think having a computer kind of helps me avoid that because I know I can always go back and fix it.

EC: What does your writing routine look like?

LB: I’m lucky because I can kind of shape my own day. I like to write two or three hours in the morning. Same time every day. I’ve done that for twenty years. I don’t even think about it anymore. I used to set these unattainable goals for myself, and then I just felt shitty. The trick is to just lower the bar and you’ll feel better about yourself. The writing comes easier too.

EC: Ah, man. You’re speaking to my heart. I get way too caught up with daily word counts and just plow ahead for no reason.

LB: It’s important to expand the definition of what productive is. Writing isn’t like coaching or playing sports. There’s no right way to write a novel. No one can come in and say, “Hey, just follow this YouTube video.”

EC: So true. Okay. I’m going to throw a curve here—

LB: Curves. That’s why I am a writer and not a professional baseball player.

EC: Well, then here comes a fast ball, straight down the middle. This is my first semester as a creative writing teacher, which, as you just mentioned is very different from being a football coach. You’re a professor at Oklahoma City University. How do you tackle teaching fiction?

LB: A lot of it is just being as supportive as possible. There’s not one way to do this. You’re gonna find your own way. It takes hard work—I do try to emphasize that—but inspiration appearing to you is a myth. You gotta have your butt in the seat, you gotta do the work, but at the same time, there’s a lot of different paths to the center. What you might think is wrong could turn out right for you. So, yeah, I try to be as supportive as possible in that way. I also try to think about the bare bones advice that I wish I’d had years ago. I started out in journalism. When I went to grad school, I knew nothing about writing fiction. I didn’t know what third person limited point of view was. I didn’t know shit. I bring myself back to that moment. There are craft elements, tools you can teach, but keep it as simple as possible.

EC: Do you have any writerly vices?

LB: Coffee is necessary to get me going for sure. I didn’t drink coffee until I turned forty. Now I can’t live without it. This isn’t a vice, but I started learning how to play the guitar a few years back. I’m really bad at it, but there’s something refreshing about learning something you don’t have to be good at. I feel zero pressure playing the guitar. so before I write, I play the guitar for like fifteen minutes. I do it poorly, but that’s almost the point. No one’s watching me, and that’s a nice segue into the mindset of writing for yourself. It’s good to have that kind of looseness.

EC: Do you have any physical regimen you implement while drafting? Like a way to get up and move and refresh your brain?

LB: I take a nap every day. I’m a fanatical believer in naps. I’ve taken a midday nap day for like twenty-five years. When I wake up, I come back and I’m fresh. I’m also a big believer in walking my dog. When I get stuck with an idea, I’m like, “Come on man. We’re going for a walk.” And he’s like, “Okay.” I guess walking is another part of the process. I’m doing something completely different and the ideas just kind of sneak up on me.

EC: So, the dog has been walked, repeatedly, and the first draft is finally draft done. What does revision look like for you?

LB: The first draft is never really a first draft for me. I stop and go back over and over. But, yeah, when I finally get to the end. I do about a month of revisions.

EC: Do you let it sit before diving back in?

LB: I’m usually so far behind on my deadline, I don’t have time to let it sit.

EC: Do you revise in Word?

LB: I used to print it out and do notes by hand, but yeah, now I just do it all in Word.

EC: Do you send it off to any beta readers? Or is it just agent and editor?

LB: It’s mostly just agent and editor. I generally want as few people involved as possible. This comes from like the post-traumatic-stress syndrome of working in Hollywood. There were so many other voices there. And it wasn’t that their notes were dumb, they just weren’t the right notes. I’m a very agreeable human being. I’m so easy going, I’m like, “Oh, that’s a great idea. I’ll do that,” But then it doesn’t work for my story. Fiction at its best is very distinctive. That’s the kind of story I want write, so I try to keep fewer and fewer people involved.

EC: Grand finale time. Why do you write?

LB: On a very practical level, it’s something I’m good at. I’m so grateful to have a been born good at something and discovered it early. So that’s one thing. The other thing is that the act of writing fiction for me is just like the best feeling in the world. It makes me feel human. When I’m writing, I’m as permeable to everything in the world as I’ll ever be. It’s just a weird woo-woo kind of thing, but it’s such a rush when it all goes well. Which makes the times when it doesn’t go well worth it.