In the summer of 1974, I was sixteen years old, living with my family in the North Texas city of Wichita Falls. I was a straight arrow of a kid: an Eagle Scout, a member of the high school’s debate team, and a cellist in the school orchestra. I volunteered at the state mental hospital with my fellow Boy Scouts, cutting lawns and trimming hedges, and every Sunday morning I attended services at Fain Memorial Presbyterian Church, where my father was the pastor. When church members asked me what I planned to do when I grew up, I told them I would most likely become a Presbyterian pastor myself, delivering cheerful sermons about the joys of the Christian life.

Then, on the morning of June 22, I walked into the kitchen and glanced at the local newspaper, the Wichita Falls Record News, that my father had brought in from the yard. Spread across the front page, in heavy two-inch-high block print, was the headline:

Millionaire Oilman, Wife Found Dead

Couple Fatally Shot in Home Here

I felt my mouth go dry. The murdered oilman was fifty-three- year-old Bobby Burns, a lean wildcatter who drilled wells all over Texas. His wife, Abbie, fifty-one, was a former fashion model who was described in the newspaper’s society columns as “charming” and “attractive” and “petite.”

Everyone in Wichita Falls knew the Burns family—or at least knew about them. They lived in the grandest house in the city—a split-level, five-bedroom mansion, more than 9,000 square feet in size, that they had built at the top of a hill on their twenty-acre estate when their four children were still young. The mansion included both indoor and outdoor swimming pools, a trophy room containing the heads of wild animals they had bagged on big-game hunting safaris to Africa, plus a two-lane bowling alley and two shooting ranges (one for pistols and the other for rifles) in the basement.

The estate itself was protected by a high chain-link fence, guard dogs, and a state-of-the-art burglar alarm system. If a prowler tried to force open a window, the grounds would automatically be flooded with outdoor lights, a loud bell would begin to clang, and another alarm would be sent automatically to the police station.

Apparently, however, all of that had not been able to keep the Burnses safe. When the police got to the mansion, they discovered the couple in their master bedroom, where they slept in separate twin beds. Bobby was found in his bed wearing green pajamas. He had been shot three times—twice in the head and once through the right wrist. Abbie, wearing a blue Neiman Marcus gown decorated with flowers, was lying on her back in her bed. She had been shot once in the abdomen, just above her navel, the bullet lodging close to her spinal column. A .38 snub-nosed revolver, no doubt the murder weapon, was on the floor beside the bed.

At that point in my life, I had read a couple of Sherlock Holmes stories and an Agatha Christie novel. But I knew nothing about actual crime. In 1974, I don’t think I knew anyone who had been arrested and taken to jail. And I certainly had never imagined that someone would execute two of Wichita Falls’ most prominent citizens in their mansion, three miles from my home.

Needless to say, I was both terrified and transfixed. Maybe, I told my friends who gathered at my father’s church for our Sunday night youth fellowship meeting, the killer was a professional thief who had broken into the mansion, stolen Bobby and Abbie’s money and jewelry, then shot the couple so he could make a clean getaway. Or maybe, I said, my voice rising, the killer was a professional assassin who had been hired by one of Bobby’s business rivals to murder them. “He could still be here, hiding out!” I nearly shouted. Two days later, however, the county’s chief medical examiner dropped a bombshell. Bobby and Abbie Burns, he announced, had not been murdered by an intruder. Forensic tests and autopsies indicated that the couple had died as a result of what the medical examiner described as an “apparent murder-suicide.” Abbie, he believed, had slipped out of her bed in the middle of the night, grabbed her pistol, shot her husband, climbed back into bed, shot herself, and then bled to death.

I simply couldn’t believe it. No one could. In Wichita Falls, Abbie was one of those women who seemed to have it all. She wore beautiful clothes and styled her hair in a Doris Day–like bob. She tootled around town in Bobby’s Cadillac or Mercedes or her own Rolls-Royce, and she flew around the country on her husband’s eight-seat private jet. Besides her skill as a hunter, Abbie was also known for her artistic talent: She painted delicate miniature landscapes on antique china.

So what could have led Abbie to commit such a gruesome act? Was it because of something Bobby had done? Was it perhaps because of something Abbie herself had done?

I began my own amateurish teenage investigation, pestering adults at my father’s church to see if they had any idea what had happened. When I went swimming that summer at the Wichita Falls Country Club with my wealthier friends, I tried to eavesdrop on the conversations that the moms were having while they lay on their lounge chairs, hoping I could pick up some rumors.

One day I decided to get a look at the mansion, which I had never seen. I asked a friend who had his own car—I hadn’t yet passed my state driver’s test—to take me there. We slowly made our way up the hill and approached the estate’s front gates, which were flanked by the tusks of a huge bull elephant that Abbie had shot on one of their safaris. Suddenly, I spied a security guard striding toward us.

“We’ve got to get out of here! I think he’s got a gun!” I cried, barely able to breathe. My friend slammed his foot on the gas pedal and raced back down the hill, his car banging over potholes.

As the summer went on, I kept waiting for the police to release more information about the shootings. But they shut down their investigation. (“Nothing to indicate Burns was not murdered by his wife who then killed herself,” a detective noted in a handwritten report in July.) Nor did members of the Burns family or their close friends reveal anything publicly about what might have led to the murder-suicide. (“I never knew two nicer people,” the caretaker at the Burns estate told one Dallas newspaper reporter. “They were thoughtful and considerate and easy to work for.”) A reporter for the New York Daily News, which was then one of the most popular tabloids in America, even came to Wichita Falls to see if he could find some answers. But under the headline “One Gun Too Many,” he admitted that he too had come up empty. “The house on the hill,” he wrote, “was a good house for secrets.”

I went back to high school to finish my senior year, and in the fall of 1975, I headed off to Texas Christian University in Fort Worth to major in English literature. I was a dutiful student: I read Shakespeare and all the great American novelists, and to improve my writing skills, I worked as a sports reporter for the student newspaper. After graduation, I decided to try journalism as a profession. I landed a job with the Dallas Morning News and later with the Dallas Times Herald, where I was mostly assigned to produce short, fluffy feature stories, interviewing celebrities who came through town. I spoke to the pop singer Connie Francis, the famed novelist John Cheever, the young actor LeVar Burton, and an eighty-eight-year-old restaurant manager named Plennie L. Wingo who was attempting to walk backward across the entirety of the United States, dressed in a beautiful striped suit. “Backward came he, backward like a crab,” I wrote in my opening paragraph. “Come on back, Plennie L. Wingo. Way back.”

Trying to be kind, my coworkers said I had a future writing fluff. To their credit, they didn’t laugh out loud when I told them that what I really wanted to do was write about people who had committed crimes.

I read Ann Rule’s The Stranger Beside Me, Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry’s Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders, and, of course, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. When the newspapers’ veteran police reporters went on vacation, I occasionally got the chance to cover for them, spending evenings in the police department’s press room, leafing through stacks of “incident reports” about car thieves, con men, purse snatchers, pimps, forgers, and other lowlifes of every description.

I wrote a story about three teenagers who stole a pig. I chronicled the life and times of two brothers who married two sisters and then persuaded them to join their home burglary ring. And every now and then, I’d get to sit on a front-row bench in a courtroom and cover a murder trial, furiously taking notes as hardboiled police detectives, the sleeves of their suit coats stretched taut around their biceps, testified in monotone voices about Dallas citizens who had shot, stabbed, bludgeoned, mutilated, poisoned, drowned, or electrocuted their enemies.

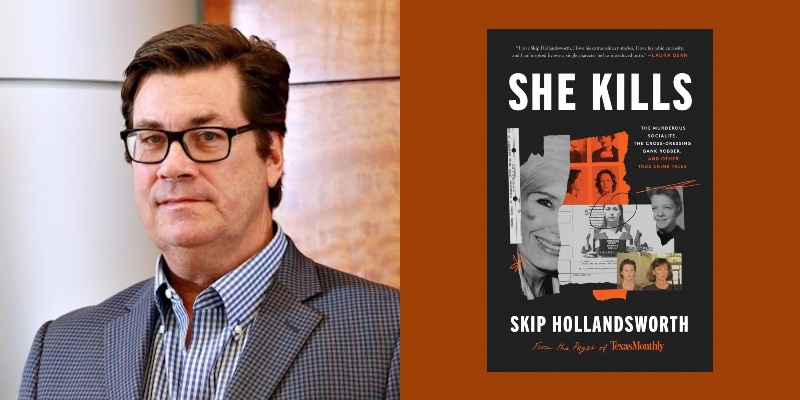

Eventually, I went to work for Texas Monthly magazine, which is renowned for its deeply reported narratives. I wrote more true crime: tales about love and betrayal, recrimination and revenge, malice and madness and sensational murder. I profiled a murderous Baptist preacher, a murderous US Air Force cadet, a murderous armored car robber, and a murderous small-town mortician. I spent days inter- viewing a highly skilled portrait painter in Dallas who late at night picked up prostitutes and cut out their eyeballs; I drank beer in West Texas with a man widely regarded as a satanic cult leader; and I followed a gang of Texas motorcycle outlaws who were involved in a deadly highway feud with another gang of motorcycle outlaws.

“Are you a yuppie asshole?” the leader of the gang asked me. “No sir, not me,” I replied, the sweat rolling down my back. But the lawbreakers who most intrigued me were the women.

Although some of them were as hardened as Texas’s greatest female felon, Bonnie Parker, the Depression-era, gunslinging partner of Clyde Barrow, almost everyone else seemed to be decent law-abiding citizens, living mostly normal lives.

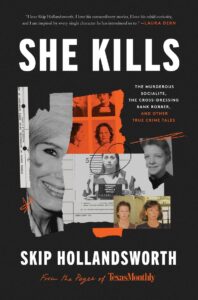

I met a devoted wife and mother from the Houston suburbs who overnight had turned into a desperate, knife-wielding killer. I spent time with a kindly nurse from the town of Nocona who every day would eat lunch by herself at the local Dairy Queen before heading off to the hospital to murder her patients. I sat through a murder trial in Fort Worth of a popular teenager who had decided that the only way her life would get better was if she poisoned her father. I hunted down close friends of a middle-aged Dallas woman who lived in a small apartment with her mother and who periodically dressed up as a cowboy and robbed banks. I researched the life and death of a glamorous Houston socialite who seemed to have a deep-rooted need to get rid of her husbands, I visited with an elderly East Texas felon who thirty-three years earlier had made five escape attempts from prison before finally getting away for good, and I went looking for a remarkable group of brazen criminals—murderers, robbers, thieves, grifters, and a heroin dealer—who were incarcerated in the 1940s at the Goree State Farm, which was then Texas’s sole penitentiary for women.

In this collection of stories, you’re going to meet these women. I also wanted, of course, to include a chapter on Abbie Burn as an adult, after starting my own career as a journalists., I did some research: I acquired Abbie and Bobby’s autopsy records and death certificates. I found the medical examiner’s written findings as well as the police department’s twenty-seven-page investigative report about the shootings, the faded ink barely visible on the pages. I called at least a dozen Wichita Falls residents who had known Abbie and Bobby, asking them if they ever had been told why Abbie did what she did. They said they were sorry, but they had no idea. I reached out to members of the Burns family. But they had no interest in speaking to me.

A few people did pass on one rumor that I actually had heard back in high school—that Bobby, who was said to have an eye for other women, had been carrying on a torrid love affair. According to the rumor, Bobby wanted to marry his mistress, but Abbie was having none of it. (“The old saying of ‘if I can’t have him then nobody can,’ might have been what was running through Abbie’s head that night,” Julie Williams Coley, a local author, wrote in her history How Did They Die?: Murders in Northern Texas 1926–1975. “Why else would Abbie kill her husband and then herself unless it was because her husband was leaving her?”)

Over the years, I also picked up one new piece of gossip—that Abbie might have had a secret life of her own. So why, after shooting Bobby, did Abbie decide to turn the gun on herself? According to the people I spoke to, she didn’t want to deal with the public shame of an arrest, a murder trial, and a long prison sentence. As one moneyed Wichita Falls woman told me, “Abbie obviously had decided she was going to go out her way.”

But again, I found no evidence that any of the gossip was true. When I interviewed eighty-eight-year-old Tim Eyssen, who was Wichita Falls’ district attorney in 1974, he told me that police detectives had never informed him of any alleged love affairs. Nor, he said, had they ever mentioned any motive Abbie might have had for wanting to kill her husband.

“So, the mystery of the Burnses’ killings seems destined to remain just that—a mystery?” I asked.

“I hate to say this, but I’m not sure this case will ever be resolved,” Eyssen replied.

Not one to let a story go, I recently returned to Wichita Falls to poke around and see who might agree to be interviewed. But I had no luck. At the end of the day, I decided to make my way up Memorial Drive to take one final look at the mansion at the top of the hill. There were new owners, of course. The elephant tusks by the front gate had been taken down long ago, and there were no more guard dogs wandering the grounds.

I put my car into park. It was a warm afternoon. Insects buzzed around my open front window. For a moment, I imagined that I could hear the gunfire coming from Abbie’s .38 revolver that night—four shots that forever destroyed a family. I couldn’t help but wonder: What was Abbie feeling right then? Was she consumed with rage? Was she overwhelmed with heartache as she reached for her gun?

I sat there for a few more minutes. A light breeze began to rattle the leaves of nearby trees. Finally, I sighed, put my car into drive, and made my way back down the hill. The story that had launched my lifelong obsession, I realized, was one I still was not able to tell.

___________________________________