There are a myriad of things that may come to mind when thinking of the creator of Sherlock Holmes: critical thinking, deductive reasoning, and the need for concrete evidence to reach a proper solution. But what about the supernatural? What about ghosts, psychics, fairies? Would you think of those?

A man seemingly riddled with contradictions, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a firm believer in all of these things, simultaneously.

In 1887, Doyle published two pieces of writing that related to these polar opposite qualities: a letter to the editor of Light, the journal of the London Spiritualistic Alliance, and A Study in Scarlet, the first Sherlock Holmes story.

Often referred to as the definitive detective, Sherlock Holmes would go on to transform not only detective literature, but detective work itself–an impact we still see today. Sherlock approached crime scenes with the attention to detail of a surgeon–no fact was neither important nor irrelevant until proven otherwise. They were simply facts. He utilized finger-printing, blood stain analysis and ballistics all ahead of their time. True, he did not invent them, but they were not as widely used as they are today.

Doyle’s hunger to learn and dedication to Sherlock utilizing these helped champion their usefulness to a wider audience. The thing to remember is forensics was still rather new–and to fully illustrate Holmes’ impact on the field, Edmond Locard, one of the fathers of modern forensic science is often referred to as the French Sherlock Holmes.

In writing crime fiction, it was important to Doyle that everything make sense. It was common at the time for a crime serial to end with a detective’s summation that would reference facts or evidence that the reader was never given before that moment. Doyle found this understandably frustrating as it didn’t give an audience a chance to try to solve the mystery alongside the detective.

It is important we talk about this key fact around Doyle’s fiction, because he attempted to apply similar meticulous scrutiny to other aspects of his life.

In his 1887 letter to the editor of Light, after reading multiple written accounts of supernatural phenomena from multiple sources, Doyle wrote, “I could no more doubt the existence of the phenomena than I could doubt the existence of lions in Africa, though I have been to that continent and have never chanced to see one. I felt that if human evidence — regarding both the quantity and the quality of the witnesses — can prove anything, it has proved this.”

He outlined that he had formed a circle of six people and over the course of nine or ten times at his home they performed seances in order to confirm the validity of supernatural phenomena. During these, supposedly messages were “delivered by tilts” and some members had written under control, but Doyle felt none of these were conclusive evidence. He was aware that the human body was capable of “playing strange tricks” unconsciously, and that a dozen heavy hands on one light table may cause involuntary shifts without help–but maintained he believed others had received the phenomena, even if he had not been lucky enough to do so.

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth,” is a famous line that originates from Doyle’s second Sherlock story, The Sign of Four.

The story itself does not really address anything even remotely supernatural–there are moments where the fantastical is briefly hinted at, but ultimately is proven mundane–but I have to wonder how often Doyle himself felt confronted by his own words? They seem to express his confusion about the number of accounts of connecting with the other side, even though he himself did not seem to possess the gift to do so. He considered himself a dabbler, a novice and inquirer–yet for all his curiosity, he found himself getting deeper into the movement, joining the Society for Psychical Research in 1893. The same year his wife Louise was diagnosed with tuberculosis.

It would have, perhaps, been unfathomable to think that so many people completely disconnected from each other, might all be telling similar, if not the same lie. It was the sort of world-wide mystery to which Doyle was not accustomed. It’s possible his judgement around this might have been further clouded by grief after the death of his wife in 1906.

Unlikely though it might seem, the man who did have the proper tools to root out charlatans was an entertainer and illusionist by the name of Harry Houdini. Houdini was an equally curious creature, but was accustomed to lies by nature of his profession. While he himself even longed for a connection to the other side and his beloved departed mother, he saw the tricks of his own trade being employed to take advantage of the vulnerable and grieving. He wanted these mediums to be real, but every time would end up exposing their methods as mere trickery.

After Arthur Conan Doyle attended one of Houdini’s shows in 1920, they struck up a brief an unlikely friendship founded on their mutual interest in spiritualism. This would later lead to Houdini attempting to prove to Doyle how easily it was to be fooled by the tricks of mediums.

In Doyle’s home, accompanied by his friend and lawyer, Houdini demonstrated a trick often utilized by mediums regarding writing the same word or phrase on a slate that was concealed on a piece of paper written by the target. Upon the demonstration’s conclusion, he said, “I won’t tell you how it was done, but I can assure you it was pure trickery. …I beg of you, Sir Arthur, do not jump to the conclusion that certain things you see are necessarily ‘supernatural,’ or the work of ‘spirits,’ just because you cannot explain them.”

Regrettably, this only resulted in Arthur Conan Doyle being convinced that Houdini himself possessed supernatural powers. Their friendship would later end after a false seance conducted by Doyle’s second wife.

Doyle himself would go on to further steep himself in mysticism, giving lectures about spiritualism around the world, opening a spiritualism bookstore, and publishing The Coming of Fairies which was based around the Cottingley Photographs by two young girls. Many people denounced these photos, and a representative of the candle makers Price and Sons made a statement that the fairies in the photographs were identical to the illustrations they used to advertise their night lights, but Conan Doyle believed the photos to be genuine until his death.

There are many reasons why a man like Doyle would stubbornly hold to these beliefs, but I like to think maybe he just longed for a little magic–something extraordinary in the mundane–something that could not be explained.

The more I read about this strange dichotomy, a question gnawed at me: could one marry the staples of Sherlock Holmes with the fantastical? What would it look like if one could bring the same forensic thought and critical eye into a world of magic? A world meant to be kept secret–a world where one genuinely gifted with supernatural power might be employed to make others who threaten to expose their way of life look like frauds?

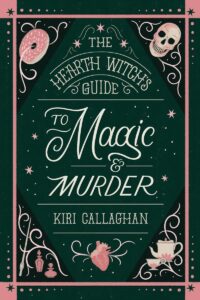

These questions laid the foundation for my adult cozy murder mystery series set in an alternate London secretly governed by fey. If you’re curious how I answered them, The Hearth Witch’s Guide to Magic and Murder will be making its debut October 7th, 2025

_________________________________