When Shannen Doherty died on July 13th 2024, it felt personal. Which was absurd, given that I’d never been in the same room as her.

Was it some kind of parasocial response? Did I mistakenly think of her as a friend, purely because I’d loved watching her kick ass on Charmed and listened to her speak her truth on her podcast while I went for long walks in my hometown? Was it emotional displacement? Was I projecting my grief over the death of somebody I really did know and love onto a TV star?

The answer, I think, is probably all of the above. And that’s okay. That’s normal. It’s all part of the power of Hollywood. Thanks to the advent of screen entertainment, TV and movie actors touch our lives in potent, mysterious ways that transcend time and space. They reach across great distances to rest a hand on our shoulders. Comforting. Entertaining. Inspiring and consoling

What I find interesting is the inherent disconnect. There is always a screen between us and the famous people we admire. As much as we feel that we know celebrities, we only know them through their work. That is why we watch interviews, read articles, listen to podcasts and endlessly rewatch their films and TV shows—we want to learn more about the people who inspire us.

As a horror author, I have picked at this idea over three novels (so far). My first, The Shadow Glass, was inspired by reports that Jim Henson was crushed when his 1986 movie Labyrinth (aka the best film of all time) flopped on release. I couldn’t help but wonder what that looked like behind the scenes, and how it affected his relationships in real life. My second novel, Burn the Negative, interrogated the allure of “cursed movie” legends and what those legends meant to the people involved.

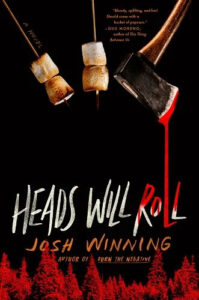

My latest book, Heads Will Roll, took its cue from “cancel culture,” aka Hollywood’s latest boogeyman. While “call out culture” movements such as MeToo and BLM rightly seek reparations for criminal activity and abuse, “cancel culture” comprises of online attacks on an individual’s identity based almost entirely on their social media activity, regardless of any actual wrongdoing.

At the time of plotting Heads Will Roll in late 2022, it seemed that every celebrity (and even non-celeb) on Twitter was involved in some sort of scandal, and the “trial by social media” furor felt dangerous, lacking in nuance and empathy. (Is it a coincidence that Doherty herself was all-but cancelled when she was fired from Beverly Hills 90210 and Charmed? Perhaps.)

I’m not the only horror writer inspired by Hollywood lives. Paul Tremblay turned to La La Land for his novel Horror Movie in order to probe that line between fiction and reality. “For certain films that we as fans watch repeatedly, we can’t help but wonder what it was like on set while making the film,” he tells me, “and there’s a weird little part of us that wishes, even if the movie depicts horrible things, that it would bleed over into realty somehow.”

Likewise, Clay McLeod Chapman, a Hollywood screenwriter and author of The Remaking, says that we find Hollywood lives fascinating precisely because they’re at a remove from our own. “Growing up, I put so much stock in what emblazoned its way across the silver screen,” he tells me. “There’s a magic to that. The notion of celebrity, of power brokering these massive million-dollar movies, the fantasy of filmmaking as this act of magic… It seemed so separate from my own personal life.”

As creatives drawing from real life, is there a risk of appearing exploitative? “If a text reads as exploitative, then it failed as art,” says Tremblay. “So, don’t fail as art? Easier said than done, of course.” Chapman has a different take: “Authors are complicit in their creations. I know I felt that way with The Remaking, so I made the conscious effort of examining my own complicity within the novel itself. I kind of put myself on trial throughout the book. I didn’t want to be spared.”

And the scariest thing in Hollywood right now? “How often money—and people who don’t know anything about story—are making the ultimate decisions about story,” says Tremblay. “That’s a frustration that is as old as Hollywood.”

“It all goes in cycles,” says Chapman, “and we’re just now entering into another compression period… but lordy, getting anything made right now feels like a miracle. With a few [of my own] potential development irons in the fire right now, I’m holding my breath and crossing my fingers/toes. It’s scary out there for a screenwriter.”

As beyond our reach as Hollywood lives generally are, they do have a way of becoming part of our own narrative. My connection to Doherty was indirect. Doherty died from cancer. My own mother died from cancer in 2004, two weeks after I turned 21. One of my strongest memories is sitting at the dinner table eating pasta while Mum asked me about Charmed. She wanted to know what was happening with the three sister witches whose personal lives were constantly interrupted by demon attacks. Those things mattered to me, so they mattered to her, too.

For me, Doherty’s death wasn’t just about losing an artist I admired and respected, it was about losing another connection to my past. Another connection to my mother.

That is why I believe Hollywood lives resonate beyond the screen. It’s why they continue to inspire me creatively. They do feel separate and at a remove. But they also feel personal. They feel part of us. And when those lives come to an end, we should grieve for them. We’re allowed to grieve for them. Because in their own unique and special way, they touched us, whether they knew it or not.

***