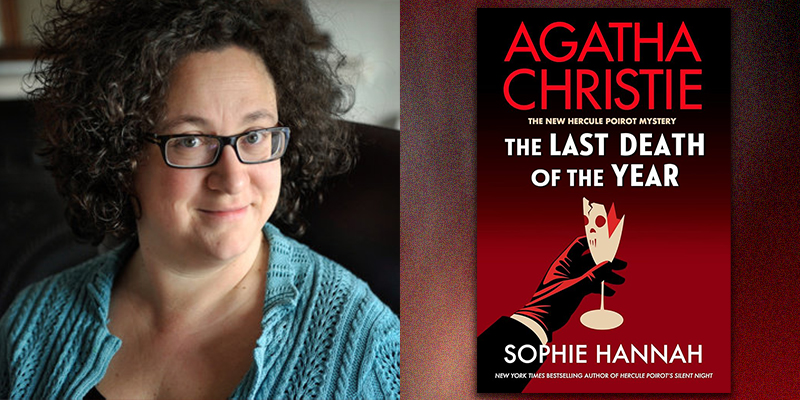

Sophie Hannah was a poet and novelist, acclaimed for her work like the Simon Waterhouse and Charlie Zailer mysteries, until 2014 when she published The Monogram Murders. The first new Hercule Poirot novel since the death of Agatha Christie, Hannah managed to masterfully craft a novel that echoed Christie’s voice, tone, and style. Set early in Poirot’s career, Hannah invented a new sidekick for the detective in Inspector Catchpool and as one who is skeptical of continuation novels, it was striking just impressively Hannah was able to make the books feel like both a Poirot story and a Christie story. That Hannah has written them while continuing to her her own novels, write nonfiction books, start a podcast, and write a murder mystery musical, is all the more impressive.

Her new book Last Death of the Year is Hannah’s sixth Poirot novel and does an excellent job of crafting an elaborate mystery and also capturing a sense of the interwar period. Hannah was kind enough to talk recently about how she writes the Poirot novels, the taunting challenge at the beginning of this new novel, and what crime fiction and poetry have in common.

I really enjoyed The Last Death of the Year, which is a great title, by the way.

I’m pleased with it. When I first thought of it as a title, I wasn’t sure, but everyone I suggested it to at the publishers loved it. So then I thought, well, it must be good if no one’s complaining about it.

This is your sixth Poirot novel and over the course of writing them, has your approach and your process changed? Do you write them the same way you write your other books?

This is your sixth Poirot novel and over the course of writing them, has your approach and your process changed? Do you write them the same way you write your other books?

It is the same way I write my other books, but the approach has slightly changed. With the first one, because it was obviously the first ever Poirot continuation, the Christie family were understandably quite keen to see a thorough plot outline. I wanted them to see one as well, because I didn’t want to write a whole book and then find they didn’t like the story idea. So for that book, I did a very thorough outline, which actually ended up being way more thorough than they’d asked for or that I intended to do. As I was doing this outline, so much detail came to me, so I just started adding and adding. That plot outline ended up being like 100 pages long. So I did that for the first three because that system worked so well. With number four, I realized that I didn’t feel the need to plan in so much meticulous detail at that point. I also started to wonder whether for the Christie family, it might be fun to read the book, the first proper draft of the book, not knowing the ending. Because, you know, the whole point of a mystery is to be in suspense and mystified. I put it to them that maybe I should just do a longish blurb rather than a full plot outline, and not tell them the ending. They all loved that idea, so that’s what we’ve been doing ever since.

After a few books they recognized what so many of us did, which is you grasped the tone, the voice, all those little things they might have worried about.

Exactly. They knew what a Poirot novel by me was. I wasn’t such an unknown quantity.

Christie famously would write a book, figure out who the murderer was while writing it, and then in the editing stage go back and plot out how to make that character the least likely suspect. How do you use the editing stage?

One of the things I always do at the editing stage is cut the word length massively. One of my tendencies as a writer is to overwrite. I always pad out the first draft of anything with unnecessary words just because I’m very thorough. With the kind of plots I construct, I have to be very thorough. When I read it through, I invariably find that I’ve said the same thing five different times in five different ways, so I can cut out four of them. So quite effortlessly, just by rereading and cutting out anything that’s superfluous, I will trim each manuscript down by between 20 and 40,000 words. The first draft of Last Death of the Year was 120,000 words. The final draft is 77,000 words. And that was easy. That was just by cutting repetition really and unnecessary stuff. It’d be great if I could figure out a way to write them the right length in the first place. I would save a lot of time if I didn’t write all those unnecessary words.

One reason I ask and this doesn’t spoil much, but the book is set before and after New Year’s Eve. Catchpool lists the group’s New Years resolutions, and he writes that you can understand who committed the murder from them. Which is such a taunting thing for the writer to do.

Although he makes it very clear that neither he nor Poirot solved the murder in this way. He’s very upfront about the fact that they totally didn’t pick up on this when they just had the resolutions. But he says now that they know who did what and why, they can see that actually, if you just look at the list of resolutions, you can see who’s a murderer and who isn’t. You can work it out. But he didn’t and Poirot didn’t. So then we go into the beginning of the story where we hear what the resolutions are. Of course, it’s meant to pique the reader’s interest and frustrate them in equal measures that they can’t work out from the resolutions who is a murderer and who is not. It’s only in the epilogue that Catchpool explains how precisely the resolutions are a clue to who’s guilty and who is innocent.

Of course it makes perfect sense when he explains it.

As with so many mysteries, it’s so obvious. One of the qualities I think Agatha Christie had in abundance as a writer, that that very few crime writers actually have, is ingenuity. She didn’t just give you a mystery and a solution. The solution was always ingenious. The reader thinks, how on earth did she do that? It’s so clever. I would I would never have thought of it. Yet it makes perfect sense.

When I’m writing any of my novels, but especially the Poirot ones, I always want to be as ingenious as possible. The key to that is often having a thing where you can lay it out in front of the reader as a challenge and say, you should be able to tell from this who the murderer is. You rely on the reader not being able to tell from that. Obviously it’s not always possible to have clues like that. I felt quite lucky that my story idea had given me that opportunity. I realized, oh, there’s a way in which I could do this so that I could say, here are all the new years resolutions. Surely you can see who the murderer is. I knew what that explanation was going to be, but I was confident no one would get it. That’s like the holy grail when you’re a crime writer. You want to be able to almost flaunt the clues and draw the reader’s attention to them, safe in the knowledge that no one will actually work it out.

So you made that decision in the process of writing it.

That wasn’t part of the who did what and why. That was part of how am I going to start? There’s always two decisions that need to be made. What’s the story? What’s the beginning? What’s the ending? But then the next thing is, OK, how do I begin this story? How do I set it up? What’s the hook? When I thought of this as a sort of prologue, I just thought, that’s the perfect way into the book. I think part of the reason I thought of it actually is because with my previous Poirot novel, Hercule Poirot’s Silent Night, I use exactly the same device. There’s a prologue set after the events of the book when it’s all over. Poirot and Catchpool are having a conversation once the mystery has been solved and Poirot makes reference to the motive for the murder. Catchpool goes, OMG, that wasn’t the motive. He doesn’t say OMG because he’s in 1932, but, how can you think that’s the motive? Poirot’s like, what do you mean? We know this is the motive. We’ve just heard the confession. Then Catchpool says something like, I’ll now tell the story and I’ll leave it to the reader to decide who was right about the motive, me or Poirot. So then you read the whole thing, knowing not only that there’s a murder mystery awaiting you, but also that Poirot and Catchpool are going to disagree about the motive. It’s just extra intrigue and extra buy in, hopefully, from the reader that will make them even more keen to read the story.

So tell me a little about Catchpool, who you created. I keep thinking of him as younger than Hastings or Japp, but he also feels sharper.

Exactly, both younger and sharper. I really wanted to invent a sidekick for Poirot who would be clever enough to be a good detective himself. Nowhere near as talented as Poirot, but that he could actually benefit from some mentoring and get better as a detective. So over the course of the six books, Catchpool has honed and enhanced his detective skills via working with Poirot.

Maybe this has changed since you started writing them, but what do you think is essential for a Poirot story?

Ingenuity, as I’ve said. I think playing fair with the reader and making very visible and clear everything the reader needs if they were to want to try and solve the mystery. That’s quite crucial. Sometimes in Christie’s novels, Poirot goes off on his own for a bit to do some behind the scenes solving, but generally, the reader is given everything they need in case they want to try and solve the crime.

Another important thing, I think, is to have a mystery hook that’s not just ordinary. In other words, not just, here’s a dead body and here are five people who could have killed that person. They’ve all got possible motives. Which one is it? That’s a normal mystery. Christie specialized in the kind of mysteries where it’s so much more mysterious than that. And Then There Were None or Murder on the Orient Express, both of those are novels where until you find out the solution, you’re going, there is no possible explanation for this. How can anyone have done it? You think it’s impossible and can’t even begin to think how this could be solved. That’s a real key ingredient, I think, that’s essential. And then Poirot’s personality is essential. All his little foible. His fussiness and his vanity. His sentimental side. His love of nice things to eat and drink and creature comforts. All of that is essential as well.

A lot of people like to make fun of Poirot in certain ways. You make a point of not leaning into that.

Exactly, but I think it’s quite crucial with a Poirot novel that people underestimate him. He can be seen to be a strange little man with an egg-shaped head fussing around. Until the moment when they all realize he’s a brilliant genius who’s going to solve everything.

This is the sixth book, as we said, and when you started, I don’t know if this was your decision or not, but the books are all set when there were no Poirot novels published.

Exactly. We agreed on that together because we didn’t want to have a prequel to The Mysterious Affair at Styles, because that’s the first Poirot novel. We didn’t want to bring Poirot back to life after Agatha had killed him in the 70s. We we picked a period where there were no published Poirot novels. Agatha didn’t publish a Poirot novel between 1928 and 1932. So that was when we slotted all of ours in.

During this novel we reach 1933, so I was curious about what comes next.

I think I just carry on going forward. I don’t know if it’s going to be anymore. We never know. I never know from one book to the next. I just wait for the family to ask me. So I don’t know how many they want in total. It could be that there won’t be any more. But if there are more, I’m just going to go forward in time from where I am.

Without spoiling much, the novel is set on a Greek island at “The House of Perpetual Welcome.” Talk a little about coming up with this group.

I’ll tell you where the setting came from. It’s a place that I have been to many times. A Greek island called Skyros. There is a big stone house on a bay, just exactly as described in the book. There’s a company that owns the house and I’ve been there to teach creative writing and things. You live in a community in that house. The students all stay there and the tutors all stay there. It’s right next to the sea. That’s where the place is based on.

The community and the slight beginnings of a cult like feeling comes from me having a very strong interest in all kinds of cults or cult-adjacent groups. I just find that fascinating. I listen to podcasts about them. I’ve read lots of books about them. I’ve been involved in things which other people have said are cult-like. I’m just fascinated by that whole topic.

Well, you would say they aren’t a cult. But kidding aside, there is a big difference between a cult and a group that can even be described as “cult-like.”

I have quite a strong definition of what a cult is and isn’t. I’ve been involved in the coaching industry and a lot of people say, oh, life coaching, it’s a bit cult like. It’s not. No one tries to force you to think anything. You can walk away and bad mouth them all day long. They never scare you or come after you. It’s just a group that tries to teach some stuff. But people love to say, it’s a bit like a cult, if they want to cast aspersions.

I’m just really interested in cults in general, and groups that all believe something. The philosophy of this group– that basically, if we want a better world, we have to be all forgiving, all the time, no matter what– I’m nowhere near enlightened enough to ever practice that. If someone pisses me off, I want to tell them to F off and never see them again. I also believe that that is possibly the way forward, if we could all manage it. Which of course we can’t, because we’re flawed humans. That’s why, without including any spoilers, it all goes horribly wrong at the House of Perpetual Welcome. Because they might talk a good game about forgiving each other, but actually, they’re full of bitterness and resentment and trying to kill each other.

Even without it being a murder mystery, the idea that it involves on a group that believes in perpetual forgiveness, I mean, we all know someone’s going to die.

Exactly!

One of the characters in the book is a poet, as are you. I’m curious about thinking like a poet. How those ideas around around language, rhythm, and structure have shaped, not just this book, but how you write fiction.

I don’t know whether it’s because I’m a poet, or I’m a poet because I have this preoccupation, but I’m always very preoccupied with the rhythm of the prose, the language, and the flow of the text being impeccable. There are some crime writers who regard themselves as primarily storytellers. As long as the prose tells the story, that’s good enough for them. I like every sentence to be elegant and well-structured. I really care a lot about the precise phrasing of every sentence.

I can see that in how you write, and I would imagine thinking about language and structure in poetry can be helpful in terms of thinking about a novel.

I think that’s why crime fiction and poetry are the two main things I write. I love a beautifully structured artifact. I’m a bit of a structure fan, so I like writing things where having a great structure really matters.