One of the things I learned when we went out to publishers with my debut novel, The Centre, is that the publishing industry is very interested in genres. In order to sell the thing, and then, to package and market it, they wanted to know what to call it. Some said the story, concerning a mysterious language school that promised instant fluency, was literary fiction, others a literary thriller, others horror, others a dark comedy, and others still, speculative. Speculative is, more or less, what most people settled upon.

The speculative in fiction is a term broad and varied, generally encompassing the genres of fantasy, science fiction, and horror. In essence, the not-quite-real. And, technically, I suppose it’s true. My book is about a translator who discovers a language school where you can become completely fluent in any language in only ten days. Not-quite-real. Then, she discovers the sinister process that makes this language-learning possible; without giving away spoilers, I’ll say, yes, even more not-quite-real.

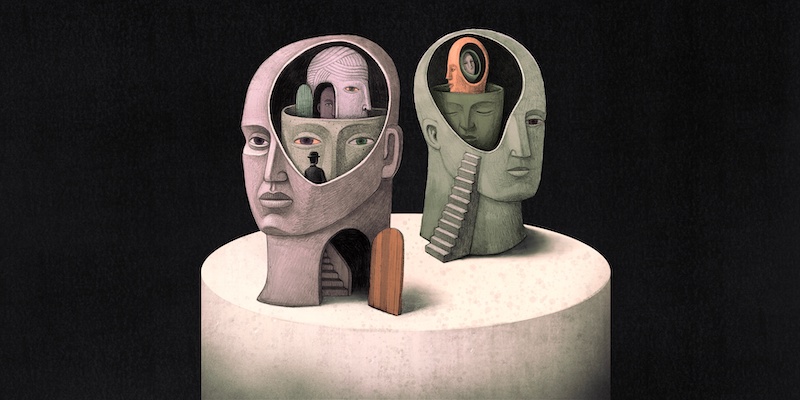

Yet, something in me balked at the label. Firstly, because isn’t all fiction not-quite-real? And secondly, what I was doing, in the novel, felt realer than real. It felt like an underground investigation into the workings of my body and mind, like a stretching of the ‘reality’ that we can see and feel in order to try and see a deeper reality beneath. But as I grew accustomed to the label, as I understood that this is the way one makes comprehensible, I started to see precisely this as the power of the so-called speculative: the fact that we can do this—that we can delve into things that, in the ‘real world’ are unlikely or impossible, contains vast potential. For one thing, it can allow us to speak in a language closer to that of the unconscious, in symbols and imagery, and to manifest, in physical form, our fears and longings, our shame and pride. It is amazing that we human beings have the uncanny ability, from when we are children, to conjure up imaginary friends and monsters under the bed. Then, if we are lucky, we continue telling such stories to ourselves and each other as we grow.

I also feel that the speculative can also have a strong relationship with the marginalized: the queer and the racialized, the neurodiverse and differently abled. It can be an avenue, for instance, to imagining a world into which that which is not meant to fit can exist. The banished parts of us, the dehumanized, the ignored and rejected, call out for space. And we have the capacity to build that space. We don’t have to contort ourselves into pre-shaped moulds. And so often, this process must begin with imagining that space.

My attempt to take a fuller, deeper breath involves my stepping into the not-yet-real. Similarly, this not-quite-real can help us understand, more clearly, the contours of our boundaries and blockages. Sometimes, in order to see the chains, you have to squint a little bit, to look askance. The strange white rabbit with his ticking clock may seem out of place, but that was precisely the point. His very absurdity was necessary in order to lead Alice into the other place. And what better way to understand the lure and horror of the spectacle than through Jordan Peele’s giant floating eyeball in his film Nope? Where are we meant to put that which within us and around us is incoherent? That which is called monstrous? Well, where better than in an actual monster? It is there in Mary Shelley’s lonely and neglected creation in Frankenstein, and it is there in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s wonderfully uncanny woman in the wallpaper in her story ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’.

In the Centre, I draw upon this long tradition of feminist body horror. Because the truth is, in order to understand the nature of the situation, it becomes necessary, sometimes, to evoke the blood and gore involved in the seemingly mundane. The woman in Gilman’s story is confined to bed rest, in a peaceful mansion by a seemingly kind-hearted husband and well-meaning doctors. And yet, it is never so simple. There is a long and twisted history behind the situation that Gilman taps into, and she shows it to us in a much more profound way than she would have by simply saying it. She takes us into the horror of it.

Some years ago, I recommended ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ to my sister. She read it before going to bed and told me the next day that that night, she had dreamt that all her baby daughter’s teeth had fallen out. I felt that this pointed towards the story’s interaction with my sister’s unconscious, to the secret, inner transmission that can occur between the unconscious of the writer and that of the reader, when we tell stories from the place beneath.

In the Centre, I tell the story of a woman captivated by the glamour and hype of an exclusive institution, and of her, then, pulling back the curtain, meeting the people that run the place, and learning of how the whole thing works. Already, even without the reality-stretching of the tale, it is a metaphor for something many can relate to—the wish for success; the desire to be somebody else; our push-and-pull attitude towards power. But then, as we learn how the language learning involves processes that are potentially grotesque and exploitative, we can open out, without being didactic or theoretical, into themes around racial capitalism and appropriation, around the hierarchy of language and culture, and more. At the same time, the book is also, on the surface, a straightforward thriller. In no form other than the speculative would I have been able to tell this story.

When the child asks to check for the monsters under the bed, the issue can be, so often, the imagined monsters within and without; we hold fears so mysterious and terrors so inexplicable that the unconscious imagines them in physical form. With story-telling, we can bring these monsters to life, have conversations with them, and learn enough about them to be able to sleep at night with a little more security and to tackle our fears more prudently in the day time. And perhaps in this way we are doing the work the psyche does in our dream life right here, while awake. This is the power of the speculative.

And then—something harder for many to swallow—there may also be the case of actual monsters. Personally, I have grown up with stories of jinns and angels, and am comfortable with the idea of invisible forces that co-exist alongside the more material, visible ones. And the dismissal of such things as ‘superstition’ or ‘magical thinking’ can sometimes feel like a euro-centric ideal that divides the world into ‘rational’ and ‘barbaric’, and that conceives of progress as a movement from a religious to a secular mentality. And so, sometimes I feel resistance towards divisions between the real and non-real, as this can evoke separations that were and still are so often used to justify all kinds of imperialist projects. But what seems to be becoming increasingly clear is that the West has no claim to higher moral, intellectual or spiritual ground than the rest of the world, and increasingly, we are questioning the idea that there is one, correct way of perceiving the world.

Of course, sometimes, this very reversal can feel annoying. Magic is, in fact, trending now. Same with yoga. Same with Eastern holistic medicine and South American shamanic brews. As if, now, popularised and then validated through western science, these ideas gain legitimacy. Marginalised cultures, translated, transformed through the Western gaze, become acceptable. It is this kind of appropriation that The Centre also explores. What does it mean to instantaneously and with barely any effort, learn another’s tongue? What are you actually acquiring, and are you taking it away, in the process, from somebody else? In the fuelling of colonialist, imperialistic agendas, we have undergone lifetimes of the dismissal, erasure and suppression of older knowledge-systems. And so, to delve back into that which is unknown, that which may appear not-quite-real, can also be a part of the power of the speculative. The seen and the unseen lie side by side, and the speculative is special because it allows for the possibility of knowing this.

***