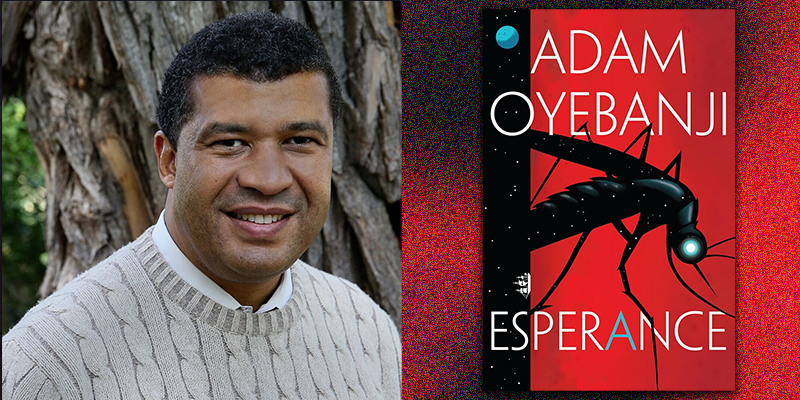

Being a writer is not glamorous. We are, after all, a profession that can go to work in our pajamas. Just occasionally, though, I’m invited to a publishing shindig and get to put on clothes. I was at one such do a year or two ago when I got buttonholed by a couple of interns. They’d read the draft manuscript of my book, Esperance, and wanted to say nice things. Being of a mildly suspicious nature, I’d say they were paid to say nice things, but these are interns. I’m not at all sure they get paid for anything.

What they both said, independently of each other, was how much they enjoyed the book and how funny it was. Now, given that my publishers describe Esperance as a thriller “plumbs the depths of a seemingly impossible crime rooted in racism, intergenerational trauma, and an inhuman concept of justice,” you might think that I, the author of this super-serious effort, would be put out by this. Quite the contrary. I was delighted. Mission accomplished!

Thrillers are often fun, light and pacy. It doesn’t mean that they avoid the hard, dark subjects. In fact, done right, it’s those “unserious” qualities that make thrillers the perfect vehicle for difficult issues. Thrillers, you see, can reach people who simply aren’t responsive to heavyweight tomes, people who hate being lectured.

If you think about it, a thriller is almost always dark. People are murdered, planes crash, buildings explode, submarines get crushed like cans as they sink to the bottom of the sea. None of this is actually fun. But the intensity of the thriller, the pace of it, carries the reader along, breathlessly enthralled. And thriller writers understand that, as in real life, dark and light often go hand in hand. Shifting to movies for a moment, Pulp Fiction is famously dark and violent, but it is also very, very funny. Likewise, Promising Young Woman, a product of the MeToo era, has scenes that are simply out and out comedic — but its message stays with you long after you have left the theater. And therein lies its power.

For a message to stay with a reader, the reader must let it in, which is not as straightforward as it sounds. The reader may pick up a book, peruse the cover and decide it’s not for them. Or read a few pages and decide it’s not for them. Or read the book while refusing to engage with the underlying message because they’ve decided it’s not for them. The challenge, therefore, is to deliver said message without turning the reader off.

Now, a great way not to accomplish this is by telling the reader they are about to be lectured on a serious and important subject. If someone is outside a theater shouting, “I want to talk at you about racism and injustice and inter-generational trauma, come on in!” there wouldn’t be many takers. Not zero, takers, mind you, just not many. And the not-many are almost certainly people who are familiar with the subject and expect to have their pre-existing views confirmed. It’s like being told to eat your greens. Some people will, for sure. But most of us? I don’t think so.

However, as cunning parents are well aware, there are other ways to get vital nutrients into the mouths of resistant offspring: like gummy vitamins. A spoonful of sugar and all that, as Mary Poppins would say. The substance of the content is masked by the sweetness of the taste. That’s how thrillers (and other so-called unserious genres like comedy and crime) get past the reader’s understandable aversion to lectures. Just spin a rattlingly good yarn (easy, right?) and the serious stuff you want to talk about can slip in unnoticed.

There is a lot of science behind this, particularly when it comes to the use of humor. There is a reason why we remember things that make us laugh, and it has a lot to do with dopamine. According to Edutopia, where a lot of this research has been summarized, humor systematically activates the brain’s dopamine reward system, which has been shown to improve learning outcomes from kindergarten all the way through to college. The more serious you are about a serious subject, therefore, the less likely you are to be effective in getting your message across. If you really care about something, make a joke about it. Better yet, put it in a thriller rather than a textbook.

We have all been on the receiving end of PowerPoint presentations that sap the will to live. Even if the subject matter seemed interesting at the beginning, the monotone delivery, the wooden repetition of words you’ve already read on the screen, the sheer earnestness of it all, end up boring the pants off you. And once you’re bored, it’s very hard to learn or remember anything.

But we’ve also turned up to the talk everyone thought would be hellishly dull and which turned out to be the exact opposite. The presenter was engaging, looked at the subject from an interesting angle and was able to crack a joke. That’s the talk you remember, the one where you learned something, almost without trying. The one that gave you the dopamine hit.

Esperance is my attempt at being the engaging presenter. Yes, it touches on race, and trauma and justice. But it’s also a fun and occasionally funny read: hence my delight that the interns had managed to get a laugh out of it.

I’m a novelist. I sit at home in my pajamas and put words onto a computer screen. I’d love for readers to come away from my books with something to think about, but mostly I just want to tell them a story, to entice them into turning the page. To make sure, when all is said and done, that they have some fun. The messaging is secondary.

I don’t think that makes me a bad person.

I know these aren’t your words but I worry that referencing praise might come across as conceited, despite you very much not being!

***