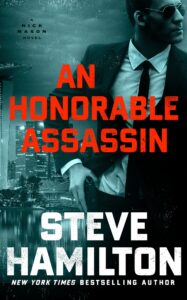

In the new Nick Mason book (An Honorable Assassin), Mason finds himself on the other side of the world, ruthlessly hunting down a target so that he can assassinate him. One of Mason’s teammates, a hardened French assassin named Luna, has this exchange with him as they wait to be rescued after escaping to a remote island:

She took a long time to answer. “You’re letting yourself feel it,” she finally said. “It’s going to destroy you.”

“How can I not feel it? I’m still human. And so are you.”

“Yes, we are human, the most savage animal on earth. We will never be anything more than that.”

Mason didn’t know how to answer that.

“You kill people,” she went on. “Just like me. That’s what we do. It’s what we are now. You can’t keep holding on to this impossible idea you have, that you’re some kind of honorable assassin. There is no such thing. It gets in your way and it’s probably going to get you killed. Maybe both of us killed.”

She’s right that Mason is trying, perhaps futilely, to hold on to at least one small piece of his own essential humanity, something that Luna seemingly gave up long ago. It’s true that Mason essentially has no choice but to pursue this mission because if he fails, his ex-wife and daughter – who think they’re safe back in America – will surely find out otherwise. And yes, the man he’s hunting happens to be Hashim Baya, a man who invests in international terrorism like it’s just another commodity.

But is this enough for you as a reader to feel true empathy for him?

Before I try to answer that, let me back up to the very beginning, when I was just starting out in crime fiction. My first main character was Alex McKnight, an ex-Detroit cop with a bullet still lodged next to his heart, currently retired to a remote cabin in Michigan Upper Peninsula. He’s a man who simply wants to be left alone but who’s nevertheless a sucker for a lost cause. If somebody comes into the Glasgow Inn looking for help, Alex is never going to refuse. Even if that means going out and getting his ass kicked again. (It’s not lost on me that the word “knight” is right there in his name!)

After a few books with Alex, I went on to write a standalone novel (Night Work) about a probation officer – whose job is literally to be the last hope for keeping someone out of prison. (Not to be confused with a parole officer, who works as an extension of the prison system, watching you like a hawk in case you screw up and need to be put back in a cell.) Joe Trumble also likes to sit in his window above a boxing gym and play his saxophone very badly, so again, how could you not root for him?

In The Lock Artist, I was finally using a criminal as the protagonist – but Michael is just an orphaned kid when he finds out that he has an unforgivable talent for opening safes. This makes him far too useful to all the wrong people, and so for him a life in crime is not even an option. Far from turning readers off, he ended up being the most “rootable” character of all.

In The Second Life of Nick Mason, I finally felt like I was ready to test the reader’s limits in empathizing with a main character. Mason is, after all, a professional criminal. He started out stealing cars as a teenager on the South Side of Chicago. Working with his partner Eddie, he later moved on to taking down drug dealers. Along the way, he developed a strict set of rules for himself. (“Rule Number One: Never work with strangers. Strangers put you in prison or they put you in the ground.”)

But as that first book opens, Mason has broken his own rules and now he’s five years into a 25-year federal prison sentence. All he wants is the chance to rebuild a life with his daughter and ex-wife, so he cuts a deal with Darius Cole, a criminal mastermind serving a double-life term who still runs an empire from his prison cell. Not only does Mason walk out through the gates of that prison, he walks right into a life of luxury – with a high-end condo on the North Side, a 1968 390 FT Fastback Mustang, and $10,000 in cash in a safe deposit box on the first of every month.

The catch? Whenever his cell phone rings, day or night, Mason must answer it and follow whatever order he is given.

I’ll admit that, even though Nick Mason is compelled to commit increasingly brutal and dangerous crimes, the fact that he is so good at it made me honestly worried that he would not win over readers – that he would ultimately be the one characters who was “unrootable.”

Turns out I had nothing to worry about. To this day, I have not heard from one single reader who has expressed anything but empathy for Nick Mason. Which makes me wonder: What is it about fiction that puts us inside a character like no other kind of writing, even the most vividly presented nonfiction?

I’m not the only one wondering about this. In a study [On Being Moved by Art: How Reading Fiction Transforms the Self: Creativity Research Journal: Vol 21, No 1 (tandfonline.com)] conducted by Keith Oatley, a professor of human development and applied psychology at the University of Toronto (and also a novelist himself), his team divided 166 participants into two groups. One group was given the Chekhov short story, “The Lady with the Little Dog,” about a man and a woman who meet on holiday and begin an adulterous relationship. The other group received an account covering the same ground as the story, with the same details and the same length, but presented in documentary form. The subjects’ personality traits and emotions were assessed before and after reading. For those who were given the story in its original, fictional form, they demonstrated greater changes in personality – clearly showing greater empathy and personal identification with the characters, and even becoming a little more like them. “I think the reason fiction but not non-fiction has the effect of improving empathy is because fiction is primarily about selves interacting with other selves in the social world,” Oatley said in an interview with The Guardian [Reading fiction ‘improves empathy’, study finds | Fiction | The Guardian]. “The subject matter of fiction is constantly about why she did this, or if that’s the case what should he do now, and so on. With fiction we enter into a world in which this way of thinking predominates.”

I don’t know if this fully explains it, because to me, fiction’s power to create empathy in a reader’s mind still feels truly miraculous – and beyond the ability of any academic study to measure. But that’s okay. I just love that it works and I’m content to remain in awe of the process, and to keep trying to create characters that you can root for, even if you probably wouldn’t want to run into them in real life.

***

Meet Steve Hamilton on the AN HONORABLE ASSASSIN book tour! – https://authorstevehamilton.com/tour/