On a hot day in the summer of 2013, I sat in my Los Angeles hotel room, waiting for a phone call from my contact, a retired memorabilia expert who had, back in the day, been known throughout the Hollywood collecting community as the guy to call if you wanted to sell an Academy Award. His name is Malcolm Willits, and I had contacted him not to try to sell one of these prizes, but to find one—one that had reportedly been missing since 1938, when it was brazenly stolen onstage during an Oscars ceremony. I had hoped that in his facilitations of various sales, he had come across this famous object. But over the phone he admitted he had not. My lead wasn’t dead, though; he enthusiastically told me he had information about the thorny legal practice of selling Oscars that might be relevant to my search. Preferring to chat in person, I took down his address. “Anything else I need to know?” I had asked him. He paused for a moment, before uttering the most cinematic thing I have ever heard in real life: “Come alone.”

There is indeed something inherently cinematic about a hunt for film artifacts. Certainly, when I first pitched this research trip to the various university departments that generously funded it, the responses I received from my advisors indicated as much. One professor advised me to write up my research findings with the diction of Sam Spade, while another jokingly referred to my project as “The Maltese Oscars.” One advisor told me I should nix the essay and instead film my whole trip (and, for effect, do so in black-and-white). Personally, I felt their stylistic suggestions had validated my project: detective movies are the ultimate how-to-guides for outlandish investigations, and I was investigating an outlandish crime.

At the time of my trip, I had counted seventy-six stolen or mysteriously vanished Oscars since the Academy’s first ceremony in 1929. (Note: today, in 2020, the total is eighty.) Sixty-seven of these prizes had been found. The stolen Oscar I was searching for was especially significant, among the nine still lost: it was the first Oscar to have been stolen. And the story of its theft, which I first learned from an Oscars trivia coffee table book when I was twelve, would make a gripping film.

But it was too late: there was no trace of the impostor who had accepted the trophy in front of so many people. In fact, his identity was never discovered, and the Oscar was never found.The legend is somewhat common knowledge among film buffs, and, for the last two decades or so, has been retold in books about odd moments in film history and in listicles during Oscars season. It concerns the actress Alice Brady, who was nominated for Best Supporting Actress during the 1937 awards (which were held in March of 1938) after her role in the film In Old Chicago. She was unable to attend the ceremony (bedridden with a broken ankle), and when she was named the winner, a man walked onstage to accept the award on her behalf. Only after Ms. Brady contacted the Academy, a few days later, asking how she should go about obtaining the Oscar she had learned she won, did the Academy appear to realize a con had taken place. But it was too late: there was no trace of the impostor who had accepted the trophy in front of so many people. In fact, his identity was never discovered, and the Oscar was never found.

I figured there were two things that could have happened to it: the man could have sold it secretly, many years ago, or he could have kept it. If it had been sold at all recently, I had surmised, Mr. Willits, who opened his Hollywood memorabilia shop, Collectors Bookstore, in 1965, would have learned about it. He hadn’t. He told me again during our meeting, at a restaurant near his home, that while he knew the legend well, he had never learned what became of the award.

No one seemed to have learned. None of my associates with connections to Oscar sales, in Los Angeles and beyond, had ever heard anything about the resurfacing of Ms. Brady’s forsaken award. This might very well have been because the award was sold discreetly, long ago, or had never been sold at all. But neither was the case. That summer, I learned the reason why my associates knew what had happened to her vanished award. It had never actually vanished at all.

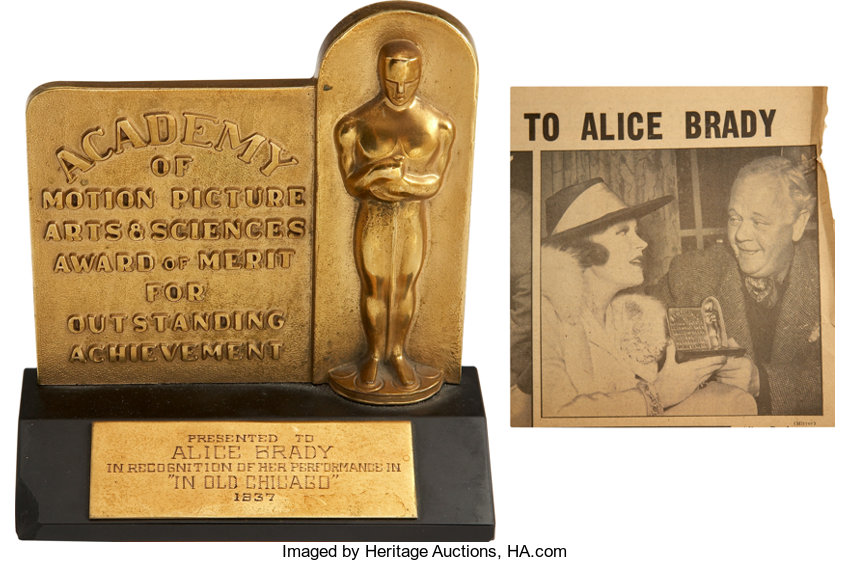

An important part of the legend of the Brady Oscar concerns the events that took place after the award was allegedly discovered to have been purloined. Apparently, Ms. Brady was issued a replacement award by the Academy, and, according to some versions of the story, she, who passed away the following year, in 1939, died before ever seeing the substitute. In 2008, Heritage Auctions sold at its Dallas location a Best Supporting Actress Award, from the 1937 ceremony, with Alice Brady’s name inscribed on the plaque (until 1943, the awards in this category were not the familiar golden statues, but plaques). According to the description on the website, this was the very replacement issued by the Academy to Ms. Brady after her award was stolen. The lot, which had been had been donated by the Alice Brady Estate Archive and went for $59,750.00, also included a newspaper clipping of Ms. Brady receiving the replacement. The clipping debunked the erroneous but persistent rumor that she died before ever receiving the substitute.

I had learned of this sale, and had seen an image of this lot—both the Award, and the photograph of Ms. Brady receiving the replacement—shortly before I contacted the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences’ Margaret Herrick Library in Beverly Hills to ask if I would be able to use the archives there to research the case. I was quickly put in touch with the Academy librarian Libby Wertin, who maintains the Academy Files. When I wrote her with my request, she told me that she knew what had happened to the Brady Oscar.

Less than ten years ago, Ms. Wertin and a colleague had been asked to research the origins of the Brady Oscar theft legend. Using various resources at the Academy Library, she had found several newspaper clippings featuring information that allowed them to trace the events of that fateful night, and beyond. Ms. Brady was indeed bedridden with a broken ankle, hence unable to make it to the ceremony, as the myth alleges. And a man did accept the award on her behalf. However, according to a Los Angeles Times article from the day after the ceremony, this man was none other than Henry King, the director of the film for which she had won the award.

An article from the June edition of the magazine Movie Mirror, entitled “Alice Brady’s Road to Glory,” notes that a troop of celebrating friends then brought the award to her at 1 am, shortly after some post-Oscars partying. She was also informed, via a ripped slip of paper attached to the statue’s base, that she should return it to the Academy as soon as possible so it could be engraved. Until 2010, Academy Award winners received blank statuettes onstage, returning their Oscars to the Academy afterwards for engraving. (After 2010, the Academy pre-engraved plates for all possible outcomes, so the winners might be able to have their statuettes personalized immediately after the ceremony).

A third article, which ran in The Los Angeles Times on March 23rd of that year, mentions that the engraved Oscar was presented back to Ms. Brady by Charles Winninger, her co-star in Goodbye Broadway, the movie she had been filming at the time of the ceremony. The Oscar was back in Ms. Brady’s possession twelve days after she won it. Its absence had her permission. It had never been stolen. There was no replacement. The award that Ms. Brady holds in the photo included in the Heritage Auctions lot was the original award (and the photo of Ms. Brady with Mr. Winninger captures his presentation of her own award, not a substitute). The Oscar that had been auctioned had therefore, unbeknownst to everyone, been the original.

A third article, which ran in The Los Angeles Times on March 23rd of that year, mentions that the engraved Oscar was presented back to Ms. Brady by Charles Winninger, her co-star in Goodbye Broadway, the movie she had been filming at the time of the ceremony. The Oscar was back in Ms. Brady’s possession twelve days after she won it. Its absence had her permission. It had never been stolen. There was no replacement. The award that Ms. Brady holds in the photo included in the Heritage Auctions lot was the original award (and the photo of Ms. Brady with Mr. Winninger captures his presentation of her own award, not a substitute). The Oscar that had been auctioned had therefore, unbeknownst to everyone, been the original.

With such a clear outline of events, it is a wonder how the legend about the mystery man came about in the first place, but it has been around for quite some time. The earliest article I have found detailing the myth is from the Edmonton Journal and is dated March 10, 1998. According to Libby Wertin, the myth can be dated to at least 1986. There is a reference to the theft in the anthology Inside Oscar by Damien Bona and Mason Wiley from that year, which the Academy library has in its collection. There are also many articles about the theft published after the mid-90s. This suggests to me that, while the myth might have been around for a while before 1986, it might not have been as commonly known or shared then as it has been within the last two decades.

* * *

Oscar thefts seem to have resonated deeply with the (late 80s and 90s zeitgeist. Whoopi Goldberg’s Oscar was stolen in 1990, one of Katharine Hepburn’s four was allegedly stolen in 1992, special effects engineer Eustace Lycett’s Oscar—won for making possible the dance between Dick Van Dyke and the cartoon penguins in Mary Poppins—disappeared in 1995, and Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni’s Oscar was stolen in 1996. Olympia Dukakis’s Oscar had been stolen in 1989, and in 2000, a truckload of 55 unmarked Oscars was hijacked. At around this time, many missing Oscars also resurfaced. Art director Lyle Wheeler’s five missing Oscars were found in 1986 (and sold in 1989), the director Lewis Milestone’s two historic Oscars (which had been missing since 1978) were located in 1990, while Margaret O’Brien’s special Oscar, won for an outstanding child performance when she was seven years old in 1945, and taken in 1955, was finally found in 1995. And in 1999, an unmarked, unassigned Oscar that had been missing since 1982 was found in the home of a California man. It makes some sense that, in this decade, with so many stolen Academy Awards in the news, a rumor about a flamboyant theft would catch on.

During the latter half of the twentieth century, interest in Oscars as purchasable or acquirable objects increased dramatically.But the decade’s abundance of stolen-Oscar-related trivia also owes its obsession with the awards to a much larger tradition of statue worship. During the latter half of the twentieth century, interest in Oscars as purchasable or acquirable objects increased dramatically. In 1950, when the Honorary Academy Award given in 1949 to Hollywood showman Sid Grauman (who had famously taken handprints of movie stars in concrete outside his famous Chinese Theatre, contributing to the cultural fascination with objects that bear traces of the movie stars who touched them) was sold at auction, the Academy, fearful of a trend involving the commercialization of their prizes, instituted a new policy regarding Oscar victories. A clause in the contract all winners sign backstage at the Academy Awards ceremony mandates that, if the winners choose to sell or bequeath their Oscars, they must first offer back their statuettes to the Academy in exchange for one dollar. All Oscars issued after that date are subject to this policy if they are being sold by their contractually-evidenced owners.

At my lunch meeting with Malcolm Willits in 2013, he explained to me many of the rules outlined by the Academy regarding the sale of these objects and shared firsthand experiences in the wilds of the Oscar marketplace, a precarious forum in which middlemen navigate the vending of Oscars that have wound up just outside of the Academy’s legal purview, while the Academy researches possible angles by which they might make legal claims to the Oscars on sale. Before I learned the truth about Alice Brady’s Oscar, while imagining it had been sold by the mystery man who took it, I had wondered if, eighty or so years ago, an Oscar’s sale, and especially a stolen Oscar’s resurfacing in a furtive black-market deal, might have gone unnoticed more easily than it would today, when Oscars are hot commodities, and consumer culture seems poised to gobble up whatever of them it can. Ms. Brady’s award was one of the early ones—issued during the Academy’s first decade as an institution, before the advent of free market Oscar transactions, or rules limiting Oscar sales, or even movie memorabilia auctions.

This is not to say that, before the popularization of these practices, or before the 1950 benchmark, any kind of stolen property would have been easier or somehow more possible to sell. It’s not even to say that Academy Awards are the subjects of greater cultural fascination nowadays. (After sifting through dozens of articles about the Oscars in 30s and 40s movie magazines, that is a claim I cannot make.) It’s only to point out that in recent times, just as Oscar circulation is more highly regulated, the Oscars also seem to be in greater and more widespread demand.

Your having the Oscar—or autograph, lock of hair, or, say, tonsils—of someone you revere forges a connection from you to them.The ceremony is broadcast live on television every year with its gargantuan Red Carpet preamble—not to mention Tweeted, blogged, Instagram-ed, and so on. Consider all this, and more: the mass of trivia books, magazine articles, and faux-statues etched with things like “World’s Best Coach” sold in souvenir shops. Consider that, during a special ceremony for which we were encouraged to dress to the nines, every third grader at my elementary school got an academic award in the shape of Oscar, cut out from yellow construction paper and covered in gold glitter. I got the reading award. Its computer-paper plaque reads “Best Director” in Comic Sans, and it is still tacked, inexplicably headless, to my bedroom bulletin board in the house where I grew up. These examples don’t even include real, tangible Oscars (indeed, the words “Academy Awards” or “Oscars” equally refer to the physical object, to the celebration, to the historical institution), a golden army of which has been issued since the first ceremony, on May 16th, 1929. My point: the Oscars are everywhere.

I had also considered that the thief might have decided to keep the Oscar for himself, or pass it on to someone. Inexpensive, materially speaking, Oscars are worth much more symbolically than they are compositionally. Stealing and buying an Oscar are two entirely different things, but both actions may follow from an understanding of the Oscar statue as embodying something great, just as much as they both might arise from idol worship or fan culture. Your having the Oscar—or autograph, lock of hair, or, say, tonsils—of someone you revere forges a connection from you to them. Maybe you deal with your love of movies by wanting to have as much of them as you can.

Oscars are trickier objects to own than artifacts which are produced by, or were once part of, someone else. They are not made by or out of that person so much as for that person. So who owns an Oscar? The Academy officially has first right of refusal, so it seems as though the statuettes really belong to the organization, even if the honor belongs to the winners. The honor is irrevocable. So why do the material objects matter—and why do they matter enough to garner thousands of dollars at auction, or to be worth the trouble of stealing? The best reason I can think of to try to possess an Oscar is the desire to have the honor that goes with it, to be made special by having it. Don’t Oscars have the power to distinguish, to celebrate? Then again, maybe the purchasing of an Oscar is less a status-enhancer and more of a faith-driven move—you hope that, by your rubbing something special, that something special may rub off on you. It is also possible that an Oscar burglar may not commit thievery in an attempt to augment his or her own status so much as to subtract such status from someone else, as if removing the signifier removes what has been signified.

Of course, Oscars signify different things to different people. The ways in which we venerate objects depend on our belief, or non-belief, in the stories, the legends, and the meanings that exist behind them. I doubt there is a more perfect tribute to awards that honor the structure and tradition of cinema than the invention of a really good story about one such award. The Brady Oscar turned out to be something of a red herring. But this is not a bad ending, although it is a familiar one. In the finale of The Maltese Falcon, the detective movie that loomed over my trip, a police officer holds the eponymous bird statuette and asks what it is that has caused so much trouble. Much like Brady’s Oscar, the physical object had been at the center of a complicated mystery, but turned out to be much less important than the hullabaloo around it. In his response to the policeman’s incredulous question, Sam Spade says simply that the statue matters because it stands for something that matters to someone. Ditching his gritty, laconic diction for a phraseology that’s both more sentimental and more Shakespearean, he remarks that the statue is “the stuff dreams are made of.”

A few weeks ago, after considering how this famous movie line might as well have referred to Oscars, I found myself on the Academy website, reading about the history of the statuette. Scrolling downwards, I saw that the section of the webpage that elucidates the composition of an Oscar was wittily headlined with this very quote. This reminded me once again that the Academy is totally aware of the symbolic power embodied by these little objects. At the risk of over-explaining, which detective movies ought never to do: stealing an Oscar is a resonant, relevant act that responds to the Oscars’ existence in the tradition of film history’s most enigmatic, exclusive, and illusive materials. In other words, while the real-life association with an Oscar can apparently validate the existence of a whole lot of things, an Oscar association has the remarkable power to turn real life into the stuff movies are made of.

In case you were wondering, Oscars are made from basically nothing of any material value. Maybe that’s the point.

*