Coming of age in the Sugar Hill section of Harlem in 1960s and 1970s, street gangs had ceased to exist in my section of the hood. Though there was talk of a crew called the Ball Busters known for beating-up graffiti artists with pool ball stuffed socks and robbing them of their paints, I never saw them; for me they were more urban myths than actual men. However in other sections of the city, street gangs were still boldly struttin’ the streets and claiming turf. In Brooklyn, the Jolly Stompers and the Tomahawks were warring over territory while in the Bronx, the Black Spades and the Ghetto Brothers induced fear in regular citizens.

In June, 1977 Esquire writer John Bradshaw wrote the in-depth feature Savage Skulls, titled after the moniker of a notorious South Bronx gang. In 1979 the article was adapted into the disturbing documentary 80 Blocks from Tiffany’s, a powerful film that takes the viewer deep into the realness of their surreal world.

Former Bronx resident and writer Paul Price, who came of age in the Boogie Down in the late-‘60s/early-‘70s, says, “I can remember when every housing project had its own gangs. There were the Savage Skulls, who were the most fearsome, The Savage Nomads, The Black Spades and The Casanovas. For a lot of young men and women, they served as surrogate families.” Thankfully, many of the young men who managed to survive past 1973 began putting their energies into the budding hip-hop culture that included graffiti, break dancing, DJing and rapping.

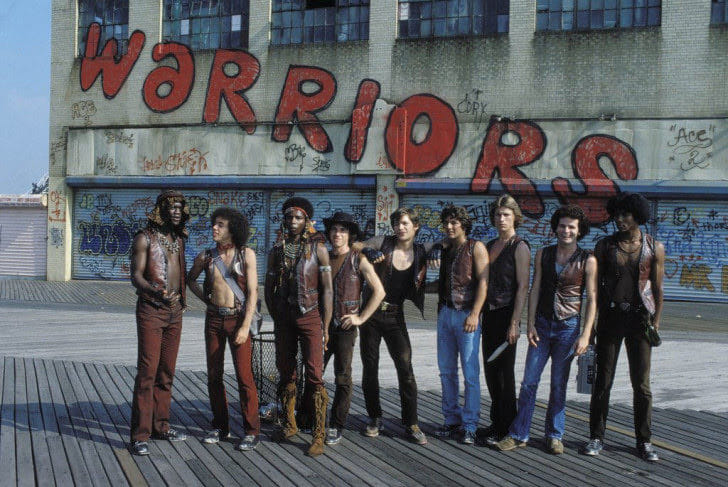

In 1979 the gang flick The Warriors was released. Depicting a city where dirty jacket wearing tough guys ruled as they ran the streets after dark, ready to rumble in a heartbeat. Directed by Walter Hill, who later claimed he thought of The Warriors as urban science fiction, the film was based on a 1965 novel by New York writer Sol Yurick.

A former social worker from the Bronx who witnessed firsthand the late-1950s rise of street gangs in the city’s poorer communities, Yurick combined his scholarly passion for the Greek classic story Anabasis with a social studies examination of gang culture, to create the simple, but suspenseful story.

“There were two films that captured the energy I was seeing (from Black youths) in the street in the ‘70s, says writer/producer Mark Skillz, co-creator behind “The Hip–Hop Shangri–La” series on YouTube. “The first film was Cooley High. The hangout crews around my way were a lot like those brothers: drinking, getting high and getting in trouble. The second film was The Warriors. Everyone was talking about The Warriors. But I never saw any gangs wearing clown makeup. I never heard of any tough guys on roller skates. Still, it was fun to watch.”

The Warriors was written during the era when juvenile delinquent (JD) fiction was still a viable paperback market, with authors Hal Ellson (Reefer Boy), Irving Shulman (Amboy Dukes) and Harlan Ellison (Web of the City) contributing to a genre of kids “flying colors,” flicking switchblades and making zip guns in shop class. Writer/editor Andrew Nette says, “The Warriors has a distinctly dystopian flavor that most other juvenile delinquent books didn’t have. You also get a very clear sense of Yurick’s radical politics in the gang leader, Ismael Rivera [named Cyrus in the film], who realizes that if he can unite the various New York gangs, there is enough power to overthrow the authorities.”

When that scene is shown in the movie, the camera pans to show the serious-faced “armies of the night,” as well as the quiet cops pulling-up outside the perimeter. However, when Cyrus, played with Malcolm X/Huey Newton-like bravado by Roger Hill, is assassinated while giving a passionate speech about street unity, all hell breaks out. Close to 50 years since its release, The Warriors has achieved legendary cult classic status and remains a powerful achievement.

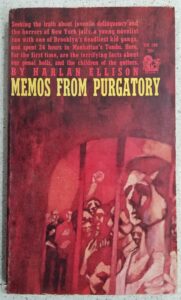

Though Harlan Ellison would later become famous (and infamous) as a speculative fiction (and mystery) short story writer, early in his career he wrote a few gritty gang narratives including Web of the City (reprinted by Hard Case Crimes in 2013) based on his experiences as an undercover member of a Red Hook, Brooklyn street gang. Three years later he published the memoir Memos from Purgatory based on the same research.

Always a masterful fiction writer, his talent for memoir, including the often long essays he wrote as story introductions, was also excellent. In 1964 Ellison adapted the autobiographical tale into a powerful segment of Alfred Hitchcock Presents titled Memo from Purgatory starring James Cann and Tony Musante. Cann played the Ellison part while the always crazed Musante plays a gang member with a short temper

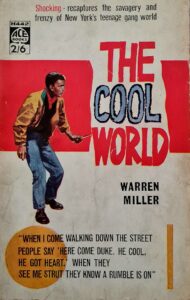

Though juvie fiction has dried-up as a market, the excellent Iain McIntyre and Andrew Nette edited the book Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980 (2017, PM Press) included essays about many of the writers, yet somehow overlooked the 1959 novel The Cool World by Warren Miller. Much like a few other JD novels including Taffy (1950), Rock (1955) and The Long Night (1958), Miller’s book took place on the streets of Harlem.

In James Baldwin’s review “War Lord of the Crocodiles,” published in the New York Times Book World on January 21, 1959, he wrote: “I consider it a tribute to Warren Miller, whose name was unfamiliar to me, that I could not be certain, when I had read his book, whether he was white or black. I was certain, however, that I had just read one of the finest novels about Harlem that had ever come my way. The author had obviously looked at something very hard. He had felt it very deeply and was trying to tell the truth about it.

“Mr. Miller manages to convey, with a masterful economy, the atmosphere of this dreadful apartment, and the peculiarly desperate apathy which has overtaken this family—if, indeed, it can any longer be called a family. The grandmother can no longer reach her daughter, and neither of them can reach the boy. He has struck out to find his own identity according to the only standards he has ever seen honored: he is the War Lord of the Royal Crocadiles (his spelling), a street gang in mortal competition with the Wolves.

“Miller tells his story in the argot of the Harlem streets. He appears to be one of the very few people who have ever really listened to it and tried to understand what was being said. In his handling, it is not strange because it is exotic; it is strange, and it is frightening, because it conveys the children’s state of mind with such force.”

In 1974 two films about Brooklyn street gangs were released. The more commercial being The Lords of Flatbush which starred Sylvester Stallone and Henry Winkler (Happy Days premiered that same year). Made in response to the 1950s revival that kicked off with American Graffiti in 1973, I missed out on viewing The Lords of Flatbush, though the TV commercial featured a catchy doo-wop song that both me and Quentin Tarantino can still recite.

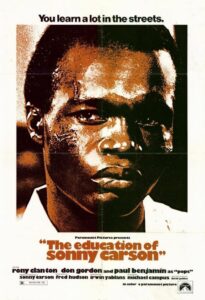

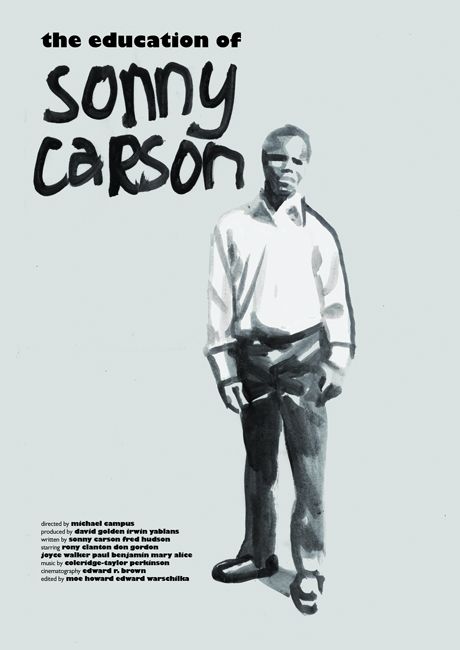

Although I was only 11-years-old in 1974, I was already watching R-rated movies at local grindhouse The Tapia. Located on Broadway between 147th and 149th, it was there that I viewed kung-fu/karate films, “Southern fried crime” features and, of course, Blaxploitation. It was there that I first saw The Education of Sonny Carson, the other NYC gang-related movie released that year.

In the history of Blaxploitation, many Black films made during that period have gotten swept up into the category, though they shouldn’t be. A few of those films include Claudine, Sparkle, Sounder and Five on the Black Hand Side. In addition The Education of Sonny Carson, directed by Michael Campus, who the year before blessed the world with The Mack, is another movie that colors outside of the lines of pure ‘ploitation, attempting to convey a deeper message.

Art by Tony Stella, https://www.tony-stella.com/

Art by Tony Stella, https://www.tony-stella.com/

The Education of Sonny Carson, based on a memoir of the same name, was a neo-realist saga told with the grit and sensitivity of Roberto Rossellini’s brutally compelling Rome Open City. Told from the point of view of Brother Sonny striving and surviving in the wild world of Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, that community serves as another character.

“If the Blaxploitation films of the time played a major role in defining modern black communities in urban spaces (no matter how exaggerated they were), then The Education of Sonny Carson provided audiences with a graphic look at coming of age in such an environment,” author Celeste A. Fisher wrote in Black on Black Urban Youth Films and the Multicultural Audience Book (2006).

From Carson’s early days when he was “a credit to his race” while accepting an academic achievement award for an essay he wrote in school, to a few scenes later when he’s been locked down in a dank teen prison, talking to his fellow prisoners through the bars, I felt his pain and the struggle to escape, but believing there no other option except gang life.

In Battle for Bed-Stuy: The Long War on Poverty in New York by Michael Woodsworth (2016) he wrote, “More commonly, gang members could be found playing cards, hanging around candy stores, drinking wine, and crashing dances.’ Sonny Carson, who would gain fame in the 1960s as a prominent Black Nationalist and protest leader, in the late 1940s ranked among the leaders of the Bishops, a notorious Bedford-Stuyvesant gang made up of black teenagers. In his telling, gang life was all about routine—to wit, his daily activities while he was nominally attending George Westinghouse High School in downtown Brooklyn.”

Carson’s memoir was published in 1972 and two years later Campus had the film in theaters. “Irwin Yablans, who went on to make the Halloween movies, had met Sonny Carson in New York,” Michael Campus told ShockCinema in 2000. “Irwin came to me after The Mack and said, ‘You’ve got to meet this guy.’ When I met Sonny I was intrigued, but after I read his book, I had to make the movie. I used the same technique as I did with The Mack. I went to Bedford-Stuyvesant and met the people, met the gangs. And it helped enormously that these people knew about The Mack. There’s no way I could have made Sonny Carson without their approval, because I worked with the real gangs. Those are not movie extras.”

For authenticity, Carson served as technical director for the film using real gang members, prisoners and community residents. In addition the film has been an inspiration for other creatives such as filmmakers Spike Lee and John Singleton, rappers Biggie Smalls and Snoop Dogg, and my own Brooklyn crime story “NY State of Mind.”

On screen there were two actors playing Sonny Carson, with Tommy Hicks playing him as a boy; he also delivers the iconic lines (“I got a message for Smokey…”) when he first meets up with the Lords, which was later sampled by Ghostface Killah on the classic track “Iron Maiden.” Two scenes later when Carson became a teen, Hicks was replaced by Rony Clanton, who was actually in his late-20s when he got the role.” Clanton was the only one in the gang with previous acting experience.

“The Education of Sonny Carson may have been the most accurate depiction of gang life in cinema until Boys in the Hood and Menace II Society came out,” Mark Skillz says. “I knew there was no way in hell that the crooked-toothed gangsta in the black jacket with the white fur could be an actor. Everything about him said he was a certified hard rock. The Education was spot on accurate in capturing the street energy I was seeing in Jamaica, Queens and Flatbush, Brooklyn.

Eleven years earlier Clanton (under the name Hampton Clanton) had starred in another groundbreaking gang drama called The Cool World (1963), based on the aforementioned novel by Warren Miller and shot in a cinema verité style. Directed by Shirley Clarke, a cutting edge filmmaker whose work should be as respected as John Cassavetes (Shadows), but isn’t, she began life behind the camera making experimental shorts in the 1950s.

Clarke made two narrative films–The Connection (1961), about a crew of Lower East Side junkies “waiting for the man” to deliver their heroin, and The Cool World, which chronicles the long days and nights of Harlem gang member Duke Curtis as he tries to raise enough money to buy a gun, or “a piece,” as he constantly refers to it.

The Cool World had already been a failure as a play, but Clarke’s friend Lewis Allen, who produced The Connection as well as Broadway shows, thought it would make a better film. “After The Connection finally opened he took me to see Warren Miller who had worked with Robert Rossen turning his novel of The Cool World into a Broadway play,” Clarke told interviewer Melinda Ward for the 1982 book The American New Wave, 1958–1967.

“The play failed after two performances and Warren and Bob Rossen were so distressed and turned off by the experience that they wanted nothing more to do with it. The rights reverted to Warren and he said to Fred (the producer) and me, “Okay, I know you and I know your work and whatever you want to do it’s okay with me. Just leave me out.

“Fred Wiseman also trusted me. Everyone’s faith in me was fabulous and it still means a lot to me. Then I wrote the script from the novel. I had decided to do a script on my own without reading the play. A friend of mine, the black actor, Carl Lee (he’d been in The Connection), helped me. Carl and I and a Polaroid camera drove around Harlem a lot and got to know streets that were to make up the life and texture of the film. I was able to write scenes for the locations that I knew we’d actually be able to use.”

Carl Lee, who a decade later became a ghetto superstar playing Eddie in Superfly, was also a featured performer in The Cool World playing Priest, the shady gun selling petty hood. Along with Lee the cast included intense, but beautiful Gloria Foster as Duke’s looking for love mother, Antonio Fargas and Yolanda Rodriguez as the young LuAnne who becomes Duke’s girlfriend. The character is naïve and mysterious, and much to the pain of Duke and the audience, disappears midway through the film.

In addition, Duke is trying to balance his shaky home life, uncertain street hustles, a junkie gang leader (played perfectly by Clarence Williams III), a new girlfriend and not getting killed during a rumble with his rivals. “I saw The Cool World with friends in Times Square and it was all kinds of exciting,” recalls Wayne Moreland, an English Department Lecturer at Queens College. “The movie was totally unlike anything I’d ever seen before. It was exciting on all kinds of levels. Though I didn’t live in Harlem, that ‘cool world,’ from my limited worldview, seemed thoroughly authentic. However, as a ramification of the movie and Miller’s book, I started reading Chester Himes and John Oliver Killens. I loved the plunge into literary blackness, even at that tender age.”

In The Cool World Clarence Williams’ young smack junkie Blood was his first big role. Having grown-up in Harlem where he saw the damage of heroin habits close up, he was realistic (and fantastic) down to the last nod. Thirty-one years later he would be equally as brilliant as the junkie daddy A.R. Skuggs in Sugar Hill (1994). The last of screenwriter Barry Michael Cooper’s virtuoso Harlem trilogy that includes New Jack City and Above the Rim, Williams brought much power to the part.

“Watching The Cool World in 1992, along with my discovery of John Cassavetes’s Faces and A Woman Under The Influence, had an impact on me as a screenwriter in general and scripting Sugar Hill in particular,” Harlem born and raised writer Barry Michael Cooper told me last year. “The first time I watched The Cool World, I think was either on PBS’s Channel 13 in New York or The Million Dollar Movie on Channel 9. I was 10 years old and in 5th Grade at P.S. 90 on 148th Street between 7th and 8th Avenues. I remember looking at the stark black and white cinematography captured by the late Baird Bryant and thinking, ‘This looks and feels like my neighborhood.’”

While I’m a fan of whatever Cooper writes, having followed him from the hip-hop/soul music writing days at The Village Voice – his 1988 story “Teddy Riley’s New Jack Swing: Harlem Gangsters Raise a Genius” was great – to his silver screen successes, Sugar Hill is my favorite of the Harlem trilogy.

“What I learned from Shirley Clarke’s directorial work in The Cool World was how it was applicable to my work in the Sugar Hill screenplay which was to find the character’s interior life and build it outward. This is what helped me consider Clarence Williams, III’s “A.R. Skuggs” and his crushing tonnage of grief and regret. Shirley Clarke’s potent films never shied away from the gorgeousness of the grotesque, because there are lessons to learn in that imperfect existence.”

Clarke, a jazz enthusiast who later made a doc about Ornette Coleman (Made In America, 1985), hired Mal Waldron and Dizzy Gillespie to do the score. “A brilliant little soundtrack from Dizzy Gillespie,” a Dusty Groove writer observed. “Composed by Mal Waldron and played by Diz with a sound and sensitivity that few of his other ‘60s albums can match.

“The feel here is quite bold and righteous, a perfect accompaniment for the documentary-like black and white images of Shirley Clarke’s film. Dizzy’s tone is wonderful – bracing one minute, blue-toned the next – and the rest of the group is wonderful too – with James Moody on tenor and flute, Kenny Barron on piano, Chris White on bass and Rudy Collins on drums. There’s a richly expressive feel to the music that makes the set hold up fantastically both as a soundtrack and as a jazz album.”

After the film’s release producer Fredrick Wiseman became a respected documentary filmmaker and has made a slew of movies (Hospital, Welfare, Racetrack) for PBS. However, for some reason he’s been unwilling to license The Cool World to home video, streaming outlets or film festivals. With the exception of an occasional pop-up on YouTube, it has been out of circulation for years.

In the 2000s, while there is no shortage of crime novels and films about gangsters, drug cartels and heist teams, the days of the street gang narratives in books and movies are long gone. The real life street gangs that exist in NYC housing projects or on the palm tree lined streets of Compton are more about dealing drugs than protecting their turf, and that change is reflected in pop culture. However, those yesteryear novels and films of wild in streets youth, gangs with cool names and ragged jackets, still hold-up decades later.