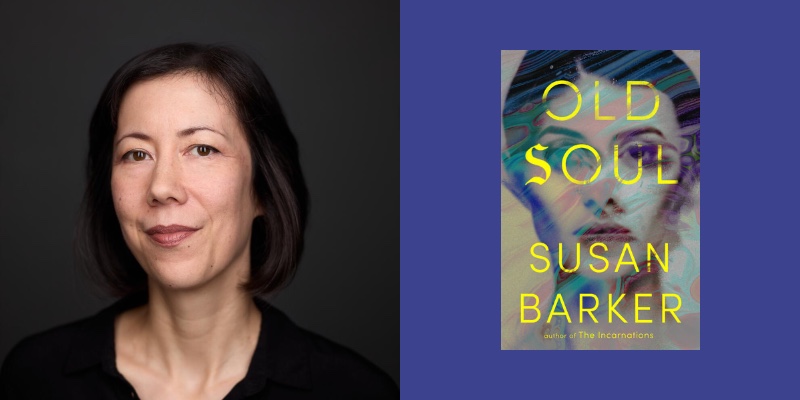

Susan Barker’s new horror novel Old Soul, a spine-chilling epic that sprawls centuries, continents, and dimensions, unfolds as a series of vignettes told to Jake, a middle-aged Englishman who still feels guilt over the long-ago death of his best friend. In attempting to track down the mysterious woman whose interaction with his friend seemed to precipitate her demise, he travels from Japan to Scotland to post-Soviet Europe to speak to survivors of the same woman.

Although the woman goes by different names and never seems to age, she leaves a trail of death behind her, and her victims all share the same eerie symptom: after meeting and being photographed by her, their bodies (from their birthmarks to their internal organs) flip from left to right. Soon after, they die. Meanwhile, the woman herself embarks on another mission to ensnare and kill a young person in the Bisti Badlands of New Mexico to keep her ancient body—and old soul—alive.

Though Barker’s previous novel, The Incarnations (2014), included speculative elements, following two reincarnated souls over centuries of Chinese history, Old Soul is her first foray into horror. This new novel blends the literary style of those previous books with hair-raising scares to thrilling effect. As she explained to me, she’s long been a fan of the genre, with Stephen King providing inspiration since childhood.

In our conversation, Barker and I discussed the nature of evil, female villains, the drive to make art, and the meticulous research she conducted to make each setting feel real. “I had no idea it would end up taking eight years,” she told me drily. Fortunately, Old Soul is more than worth the wait.

Morgan Leigh Davies

In the press notes for this book, you talk about wanting to scare the reader, which was certainly my experience of reading the book. What appeals to you about writing horror?

Susan Barker

I really enjoy being scared myself. I love that feeling of dread and adrenalized tension you feel when you’re watching something or reading something, and you don’t know what’s going to happen next, but you know it’s going to be something bad. Because I enjoy that so much, I’m trying to make the reader feel it, though I know it’s not everyone’s cup of tea.

MLD

The plot in this book jumps from person to person who’s encountered the woman, across time and place. What did you feel you could get out of that episodic structure?

SB

I’ve always been really drawn to multiple-narrative novels, and all of my novels have different narrators and points of view. My last two books move through history the way Old Soul does. I’m really led in what I write by what I’m curious about. My third book, The Incarnations, is set in contemporary Beijing, but is interspersed with historical narratives that span millennia of Chinese history. It ends in Communist China. I realized I didn’t know much about the former Eastern Bloc, so I thought, Okay, I’ll set something there. I just started researching and stories grew out of the research.

The settings are geographically quite diverse – and, in terms of different periods in history, too – which is what I’m interested in writing and also how I understand the world. My mom’s from Malaysia. She emigrated to England. I moved to Japan. After I graduated, I lived in the States and in China. I have relatives that moved from the UK to Australia, from Malaysia to America. So it’s how I understand the way people are now.

But in the case of Old Soul, Jake is also on a hero’s journey. He goes around, he meets people, he gathers their testimony. He gains more insight into who the woman is, what her modus operandi is, and the pieces come together in a puzzle that fits together by the end. I find that sort of structure quite satisfying.

MLD

You use the word testimony to describe those chapters. It really struck me that, by necessity, these stories are coming from the survivors left behind afterward, though we do also have these chapters that that are from her point of view. But so much of the information that we’re getting is from people telling the story after the fact. How did putting that together work?

SB

I’m really fascinated by the psychology of evil. What makes people act with such self-interest that they override the rights of other people? The woman sacrifices people’s lives. I wanted to explore who she is from her interiority, so the reader sees her vulnerability. We see her physically suffering in the Badlands. But I also try to get across the ways that she’s deluding herself in the way that she lives: her belief that she’s complete, she doesn’t need any kind of human connection, that she’s different from other people. She has a kind of disdain for humanity. She sees herself as having transcended it in some way. But I think the reader sees through some of that, and it’s another kind of vulnerability.

Then you have the perspective of the characters that meet her, and maybe sense that something is off about her. She enters their lives, she exits their lives, and then the supernatural consequences of that slowly build up and start to escalate. That’s a really fun thing for me to write. That brings in the fear, aspect of the of the story: inhabiting the character’s mind as they’re trying to figure out what’s going on, did they just imagine that, or does do they look a bit different? Is it me?

I recently read Danse Macabre by Stephen King, and he differentiates between the different emotions that horror can evoke, and puts them in a hierarchy as well. There’s terror, horror, and disgust. Terror is the part before the monster appears, the dread and suspense of the appearance, the signs that the monster is there. Horror is the appearance of the monster. And then disgust is the visceral blood and guts. I like writing in the area of terror.

MLD

How did you think about how much to deploy the more concrete or physical signs of what happened to these characters, or, if we use King’s parlance, the horror within the book?

SB

I knew I would have to show the monster. Spending eight years writing the book, I can’t remember any eureka moments when I decided that the characters’ internal organs would be reversed, that they would be psychologically manipulated, or that the creature would invade them. It all built up slowly, but I always knew that these are the manifestations of the monster before the appearance. I always knew it would be an extra-dimensional thing. I’ve always really liked HP Lovecraft, and the fourth dimension of space has always been an interest of mine. In my first book, Sayonara Bar, which is set in Japan, there’s a character that believes he can transcend to the fourth dimension. But it’s a theoretical dimension. The third dimension is obviously a lot more complex and sophisticated than the second dimension, so a fourth-dimensional creature looking down on the third dimension can see everything at once, can see inside people, outside people. It’s quite hard to describe, but basically, we’re on the sheet of paper, and it can move us about and manipulate us like chess pieces and reach inside us.

Obviously, I’m not a scientist; it’s just a creative source of inspiration. I always had a sense the monster would be like that, but the characters couldn’t truly perceive him, because he’s in another dimension. They only have like senses to see in three dimensions, but the flipping of the organs is to do with moving between dimensions.

MLD

I’m also curious about the patterns between the dynamics of the stories of victims in the novel. There are a lot of dysfunctional families, but it’s not as though every story follows the same beats. Was there a certain kind of kind of relationship that you were trying to explore in those in those stories?

SB

I always write about really complicated relationships. I think it’s like a recurring theme in my books, power struggles between people and the state or politically, but also between people as individuals and difficult relationships and family situations. The woman is a predator. I think she’s really good at seeing the things people are insecure and vulnerable about, bolstering their ego, making them feel validated. That’s a really addictive feeling, when you feel as though someone really sees you and gets you. I get why the characters feel really infatuated by her, because she makes them feel good. But you have empaths, and I think there’s a variety called dark empaths, where they see you, they get you, and they will use that for their own ends.

MLD

Part of what interested me about her is that she’s just really evil. The fact that she’s a female character makes her unusual, because normally, the sociopathic killers that we encounter in fiction or in true crime are men. What’s appealing about writing a character like that? Is there anything tricky, or fun, about writing someone who’s so totally self-motivated?

SB

I’d read The Picture of Dorian Gray at the start of writing Old Soul and it was a big influence. Initially, she was a man who painted people’s portraits. I wrote pretty much a whole draft with him as the primary antagonist. Something wasn’t working. The prose was a bit flat, and I don’t know why, but I flipped the gender, and then I got her, and I understood it more. It made the dynamic between her and her victims much more interesting, because a woman, even one aided by supernatural powers, is more vulnerable.

I think it’s interesting that she’s a woman as well, because, as you’re saying, it’s less common. It’s seen more as an aberration of nature. I think, when a woman is sociopathic—and I’m not even sure that she is sociopathic; she does have empathy, but she’s able to justify to herself what she does—she’s a subversion of a lot of values that we think women should have, like being compassionate and nurturing and caring and maternal. She’s none of that, unless she’s performing those things to manipulate people.

When I was writing her, I think I was channeling my own feelings of being an aberration – or a deviation from the norm in some way – into her creation. I think all women feel a lot of pressure to be a certain way or to perform certain values. I definitely channeled a lot of feelings of deviancy into her — far lesser transgressions, I’m not sacrificing people [laughs], but, you know, I don’t have kids, I’m getting older — that’s another deviation from the feminine ideal. The list goes on.

MLD

In those sections from her point of view, you write about her body and appearance breaking down and describe it really vividly.

SB

It was a lot of fun researching how the body decomposes. She does become like The Walking Dead. I read a lot of books about what happens to the body after death. I read a book by a forensic pathologist, who does an autopsy on a corpse to find out how it died. It was fascinating. I was able to put in loads of gnarly descriptions about how the immune system stops and bacteria start to break through the intestine, then they start to attack the organs, and organs start to putrefy.

MLD

The woman also has this relationship with Theo, the sculptor, which is the emotional climax, in some ways, of the book. At what point in the process did that part of the story emerged? Why did you want to include this vulnerable side of her?

SB

She’s lived for 300 years. I think she’s been made into what she is, which is someone concerned with survival. I think she thinks that just being alive and in the world is enough for her. I knew there had to be someone that she does have a connection with, and that connection causes her to question her entire way of life.

I also love that idea of a solitary artist just going into the wilderness to focus on their art. I think DH Lawrence lived in Taos County, and Georgia O’Keeffe and Agnes Martin; they just had these studios in the middle of nowhere. I thought it would be cool to have a sculptor that has the same sort of setup, but she’s struggling, she’s lonely. I originally wrote Theo in third person, but when I flipped to first person, her character really came to life from me—I knew her, and her voice. When I started to write the diary entries, her voice as a personality and point of view really came to life.

I think they have similarities. They’re both sort of in exile. They both cut themselves off from other people because of something they believe in: for Theo, making great art is the purpose and meaning of her life, and for the woman, it’s life itself. I think they admire each other and they connect in that way. They’re a good match, but the woman obviously can’t settle down. It would sabotage her way of life.

MLD

I liked this sense them having this idyll, in a very temporary way. But then Theo has the slow revelation that something’s very wrong.

SB

I think everyone’s been in a relationship like that. I mean, not with someone who’s serving an otherworldly entity, but with someone who is evasive. It’s not quite right. I think Theo has made herself not ask too many questions, because she’d rather be in a relationship like that than lose her completely.

MLD

I also wanted to ask about the role of art-making in the book, which you just touched on. How did you thinking about how the characters using art in different ways? The woman is a photographer, Theo is a sculptor, there are other examples.

SB

I really like this book A Denial of Death, by Ernest Becker. It’s about death, about how a lot of human activity is a sublimated fear of death and our desire to leave a legacy after we die: having children, or doing political work, or art-making. It’s also a way to acquire status, because we’re aware of the impermanence of life, and we want our life to be important, to stand out, to mean something. I think some of the art-making in the book is geared that way.

There are a lot of visual artists in the book, because I love visual art. I’m also quite envious of visual artists. I’ve done a lot of artists’ residencies over the years, and writing is such an introverted occupation. You’re at your laptop, you’re hunched over; you can do readings, but writing’s not as immediately graspable as a lot of visual art. Artists do studio tours, and it’s big and extroverted, and their art is everywhere. I was always quite envious of the difference in the process. I think writing about artists is a vicarious way of experiencing it.

MLD

In both Old Soul and your previous novel, The Incarnations, you use a massive time span, beyond a single human life. Where does your interest in big, metaphysical questions, like fate and destiny, happening over this impossibly long period, come from?

SB

I’ve always been interested in the context of history. When I was writing The Incarnations, it was partly about the effect of really rapid socio-economic change on ordinary citizens in Beijing, but it also looked back on Chinese history. With Old Soul, I was interested in how the woman has been shaped by history. We go all the way back to St. Petersburg, and see her lower nobility origins and her oppressive circumstances. She changes and adapts to every time; she learns the language; she learns the social mores and mostly conforms to them.

One thing I wanted to convey was just how fleeting an individual human existence is in terms of its span of years, and also how fleeting the human species is as well. There are a few chapters set in the Bisti Badlands in New Mexico. The woman and the girl are walking through a landscape, and the rocks beneath their feet are, like, 70 million years old. They date back from a time when the there was a lush rainforest there. There was an inland sea splitting America in two, there were dinosaurs about for 200 million years, which puts the span of humanity, which is 200,000 years—it’s just nothing. Even though the woman has existed for a really huge chunk of history, she’s really aware of the fleetingness of it. But in fact, I’m pretty sure that this desire to be in the world and her acute awareness of her mortality, this really powerful survival instinct, is something that’s been put in her, because she’s in service of this higher power.

MLD

Before we go, I would love to know if you have any recommendations of anything you’ve read recently that you loved.

SB

I read You Like It Darker, Stephen King’s collection of short stories, over Christmas. When I was growing up, I read Skeleton Crew and Night Shift, and I think I learned a lot about storytelling and craft from reading those books and it I really enjoyed You Like It Darker. Reading Stephen King is really nostalgic for me; it’s comforting. I recognize his voice on the page, even though the stories have horrific moments. They’re quite unnerving and suspenseful. I’d recommend that for Stephen King fans, or just horror fans, or fans of literature.