If you read comics, you know Ed Brubaker. You’ve probably read part or all of his notable writing stints on characters like Captain America, Daredevil, Batman, The Authority or his own properties, like the noir anthology Criminal, the horror-crime mash-up Fatale, or the vigilante send-up Kill or Be Killed, the latter three in partnership with longtime artistic collaborator, Sean Phillips. When you think crime comics, Brubaker is usually one of the first names that come to mine, which is a testament to the level of quality the writer’s maintained over two decades of producing comics for established characters and his own, equally popular creations.

That said, Brubaker might not be as recognizable to crime fiction readers who aren’t well versed in graphic novels, or familiar with comics in general. But if you’ve seen and enjoyed media based on Brubaker’s comics, like the Captain America: The Winter Soldier film, for example, then you’ve at least gotten a taste for what Brubaker brings to the table. But why stop there? It’s time to dive into the seedy, dangerous worlds of Ed Brubaker.

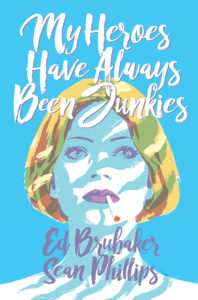

Brubaker’s work—even his more mainstream super-hero efforts, like Uncanny X-Men or Captain America— are steeped in the timeless elements of classic mystery and noir fiction, with conflicted and desperate characters exploring the dark, gritty underbelly of society with settings pulsing with personality. Whether it’s teenage junkie runaway Ellie conning her way through the pages of Brubaker and Phillips’ latest, My Heroes Have Always Been Junkies, or the twisted and bloodthirsty vigilante, Dylan, from their acclaimed Kill or be Killed series, Brubaker presents raw, relatable and intense portraits of the modern struggle, with a knack for shocking twists and double-crosses, and a punk rock ethos that gives his work a jolt of originality and verve.

I had the chance to chat with Brubaker about Junkies, just released as a graphic novel by Image Comics, his previous comic book work, his upcoming TV projects and the pros and cons of writing established, company-owned characters.

SEGURA: My Heroes Have Always Been Junkies was released as an original graphic novel, which for the comic book layman, means it’s an entire, original story, as opposed to something that comes out as single-issues first. I believe this is a first for you and your frequent collaborator, Sean Phillips. What made this a story you wanted to tell in this format?

BRUBAKER: I think primarily it came out of us just loving the format and wanting to do something that wasn’t serialized. I love doing bigger stories chapter-by-chapter, like with Kill or be Killed or The Fade Out, but some ideas just don’t break down that way and have the same impact.

Junkies sort of appeared to me all at once, and I knew it wouldn’t work if I had to add two other endings in the middle of the story, you know? And it was really freeing in some ways to know people would read it from start to finish in one sitting, most likely. I felt like it gave us more control, creatively.

Writer Ed Brubaker

Writer Ed Brubaker

What can you tell us about the book’s protagonist, Ellie?

She’s an 18 year old in a rehab clinic, but she’s not there by choice or because she thinks she needs to be, so she’s the asshole in the group. She’s the one who fucks with the counselors and glamorizes drugs and drug addicts. And of course, she’s got her own agenda. And she’s lying about some things, obviously.

The whole novella is really a character study of her wrapped around a crime story that she’s part of, but all the moments where she talks about her history and her mother—who was a junkie that died when she was a little kid—those scenes reveal a lot about her, about her truth. And for me, she’s a very tragic character, because she’s haunted in a few ways by a love she only vaguely remembers.

I’d describe the book as haunting—largely due to those flashbacks, which are just gutting. The story as a whole feels very tight—compact and, thematically, very well thought out. It’s rare in comics to feel like a story is ever complete, if that makes sense. And while there are some connections to your earlier noir comic series, Criminal, Junkies stands alone in a really impressive way. Can you talk about that a bit, and maybe what influenced the original graphic novel?

Well, my main goal with all the Criminal books has always been to make sure you could pick up any of them and read them out of order, and not feel like there was anything missing. It’s more of a shared world, like Elmore Leonard’s books were. Like, I think if you read them all they add up to something bigger, but each one is its own thing.

So with this book, it was all about finding the voice of the main character, and making the pieces all fit together. I obsessed about making sure the structure, the two story strands weaving around each other, came together at the end, so that it (hopefully) felt satisfying.

And the scenes where Ellie is talking about her history were really important to me because they’re loosely based on my own childhood, going to my mother’s meetings all the time. Seeing junkies and alcoholics tell stories and cry and laugh about tragedy when you’re an eight year old kid has a big impact on you, and it’s something I’d been trying to find a way to write about for a long time.

Giving Ellie some of that history, but making it a crime story, allowed me to find a way to get that stuff on the page. It gave it some structure and a bit more tragedy.

Definitely, and it shows. What I loved about the book—hell, all your books—most recently The Fade Out and Kill or be Killed—is that they occupy a bigger world, not just in terms of character and story, but in literature. I think people often have this misconception that comics are just…comics, you know? But you don’t hesitate to talk about things outside of the format that influence you—from movies, novels, TV, etc. What were some of the big things bouncing around your head when you wrote Junkies?

I guess I make some references that aren’t so much pop culture as they are just culture sometimes, like paraphrasing a 1001 Nights story in Kill or be Killed, or talking about Fitzgerald’s time in Hollywood a bit in The Fade Out. And to some degree, Kill or be Killed was a narrative voice that was examining what it could do, and breaking the rules as it talked about them. For me, this is just about trying to make every story as rich and full as it can be. I want them to be layered with details and character like any good novel, because that’s what I want from the comics I read, too. You know?

For Junkies, mostly what I was thinking about as I was writing was just trying to channel a specific kind of sadness I feel into Ellie’s voice. I was also trying to write a sort of “unreliable” narrator story where the narrator is actually telling you the truth the entire time if you go back and reread it.

What can you tell us about Sean’s approach that was different? I know Jacob came onboard to color, for one.

Sean started out back in the 80s as a teenager drawing girls romance magazines in the UK, so he really wanted to do something that connected back to that part of his career. So he kept the art very open, with less black on the page, leaving a lot for the color to do, and knowing it was going to be a kind of limited palette, but in a very different style. He was initially going to color the book with Jake, but then Jake did such a good job and the deadline was so tight, that Jake just took over after the first few pages.

You’re a longtime fan of crime fiction and mystery novels. I think we’ve talked about Ross Macdonald a few times, who’s one of my biggest influences, and I believe yours as well. Can you talk a little bit about the novels that defined you, and when you read them? I know you moved around a lot as a kid. How important were books and comics to you early on, and how do you see those influences still playing a part in your work today?

Oh yeah, I was a Navy brat, so my books and comics were my lifeline. I spent most of my childhood alone in my room reading or drawing, or watching old movies on TV. Ross Macdonald was a big revelation to me, because of how much he put his own family history and his own trauma into his mysteries. I mean, his structure was so perfect that I feel like it just became the structure of almost all mystery novels for a while. Before reading the Archer books, most of the crime books I read were more the noirs—Jim Thompson, David Goodis, Frederic Browne, like the Black Lizard press stuff from the mid-to-late 80s. I just devoured a lot of that stuff when I was growing up, and a bunch of true crime books. My first two crime comics were both loosely inspired by actual crimes that happened near where I lived at different times, girls that got murdered—one by a cop and the other by her boyfriend, who then came back and had sex with her corpse, according to his confession.

Influences are weird, though, because once you’ve been writing for a while they just become forgotten. They fade into the background. Like when I first wrote a mystery I wanted it to feel like a modern day Archer type of book, but nowadays I would never think about that. I just think about the characters and their journeys, you know? And I think about trying to top whatever I did last, or at least take a left turn or something.

I love how you describe influences, yeah. Because no matter what you’re riffing off, it still has to go through the filter of, well, you. And that means it’ll be inherently different, no matter what.

To zoom out a bit: you’ve built up a really nice, recognizable corner or the market for yourself with creator-owned comics. To the point where, if someone discovers you today, they might not immediately realize you also had a long, storied career writing company characters—like Batman, Sleeper, X-Men and, probably most noticeably, Captain America. I’m particularly fond of your Daredevil run, which, I think, doesn’t get the praise it really deserves. From my perspective, it seems like you’re done with that chapter of your career. Aside from sheer creative control, can you talk a bit about the differences that come with writing your own characters and those that are owned by Marvel or DC, and the pros and cons of either approach?

I mean, the con is they can take something you co-create, like the Winter Soldier, and make hundreds of millions of dollars on toys and hoodies and cartoons and movies, and basically give you nothing—or nothing’s next door neighbor, if you’re lucky.

The pro is that you can have fun and make a good living as a writer while you’re doing it.

I worked really hard on stuff like DD and Cap, and I’m really proud of what me and my collaborators accomplished on those books. Stuff like Gotham Central and Catwoman was where I built some of my readership, by doing crime comics with superhero stuff in them, but ultimately, I always wanted to just write my own stories, I think, regardless of the fucked-up contracts in the superhero field.

But I think, in general, my process was mostly the same, as far as plotting out the books and writing them. With superhero comics, a bit of the work is done for you in advance, by the readers knowledge of who everyone is and what their world is like. People picking up Captain America have a good idea of what they’re going to get, you know? And you can play with that expectation, which is fun sometimes.

In the end, the reason I burned out on superhero comics is they have the same last act, for the most part. People put on costumes and fight and the bad guys win, and that was never that interesting to me. That’s why my early superhero comics are all about the loser’s perspective. The cops who can’t solve the crime without Batman, or Catwoman’s friend who is traumatized by killing someone, or something like Daredevil where you can have Matt Murdock lose all the time and go to jail.

I like flawed characters who make mistakes and don’t win and them not winning, well sometimes that’s the beginning of their story.But with my own comics, stuff like Junkies or Criminal or The Fade Out, it’s just like writing a novel in comics form, you know? There might be genre conventions in the books but ultimately they’re stories that begin and end and the main characters are protagonists more than heroes. That’s just more interesting to me, as a reader and a writer. I like flawed characters who make mistakes and don’t win and them not winning, well sometimes that’s the beginning of their story.

It’s interesting that you say you plot all your comics the same way – can you talk a bit more about your process? I may be wrong, but I feel like I read somewhere that you’re not a big plotter before entering the script stage. Is that true? Can you talk about how you and Sean work together?

I’m one of those “I have to know where I’m headed” kind of writers, but not in the—what is that thing, how either a writer is an architect or a gardener? Like a gardener knows what kind of plant they’re growing but isn’t 100 percent sure what it’s going to look like in the end. I think I’m more that, now. I used to have the most insanely detailed outlines, and for The Fade Out I went back to that to some degree, but usually I prefer to keep my outlining a bit loose. I know where I want the story to go, but not how it’s going to get there. I like that freedom, to keep my own interest on the page as I write. But it can be frustrating too, knowing I have a goalpost I want to get to and struggling to make it all fit together.

I notebook a lot, but a lot of it is character stuff that doesn’t even end up on the page. Just stuff I know about the characters and their histories, so I know what they want and what they’ve done and what they’ve lost.

But my outlines are fairly spare now, and I plot out the longer stories chapter by chapter. Again, knowing where they need to go and hoping they end up there, of course, but I will often end a chapter with just a handful of ideas about what happens next. Sometimes that works better than other times. I’ve written enough books now that I have a bit of a gut instinct for the structure, so that makes it a bit like having a net. And if I get stuck I can always pull out a notebook and do a tight outline to make sure it works. I’ve done that before.

I love the “architect vs. gardener” idea, because I’ve always thought that writers rarely fall into either the “pantser” or “planner” category—most are somewhere in the middle.

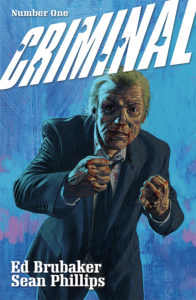

One thing I wanted to touch on, because it relates to planning a bit, is the return of Criminal, which comes back next month from Image Comics, by you, Sean and Jacob Phillips. Did you know you’d make your way back to the world at some point?

We always assume we’ll do more Criminal, because it’s like this world we keep adding to over the years, and it’s always like coming home to do more stories in that world, but honestly until I was halfway through the Junkies book, I was planning something else as our next monthly comic.

But getting Junkies finished and ready to print, I had this sudden rush of ideas for Criminal stories, and just decided to bring it back as a monthly and try to do some different things with it.

What can you tell us about the process of bringing it back?

Well, one of the things my editor/publisher Eric Stephenson and I have talked about for a while now is that a lot of comics, really almost all of them, even from Marvel and DC, are now serials written for the trade. The single issue itself has started to become an afterthought. At the big two, you have tons of ads in them, and they’re on cheap paper now. It’s like this amazing little package that gave us all decades and decades of joy as comic fans is being neglected by the market that was built on them.

So that was a big part of what motivated me. I had ideas for some shorter stories, and some ideas about how to make Criminal as a monthly comic something that would really stand apart in the market. We’re really embracing the format itself, so you never know from issue to issue exactly what you’re going to get. Some issues are just a single short story, some will be part of a larger arc. Some will actually feel like a bunch of single issues until you realize they are adding up to something bigger.

It’s been exciting so far, and challenging, but I really want to give readers a reason to be excited every month, and hopefully give them something they’re not expecting at the same time.

What can you tease about the new series?

The first issue is basically the ultimate Criminal story. It kind of shows you everything that the book does, all in one long and winding oversized story.

Here’s a few pages from it to tease it better than I can.

I think we talked about this years ago, but you were one of my first comic book interviews—well over 15 years ago for a blog I launched (The Great Curve, for those keeping score). At that point, you were just getting rolling on Sleeper for WildStorm—if I’m not mistaken, your first collaboration with Sean—and heading toward more work with DC and the Big Two.

That must have been between the first and second runs of Sleeper, I think.

Right, you’re absolutely right. Anyway, Sleeper’s a dark, twisted book with a lot of heart, and it really carves out a personal story out of the WildStorm universe at the time, which was very loud and in your face. There are a lot of elements in that book that I can see carrying over to your subsequent work, themes of isolation, anti-establishment and a great love for the tenets of noir. I don’t know if you go back and reread your older work, but what do you remember about that time of your career? Anything you’d want to relay to that younger version of yourself if you could?

Oh boy, my biggest advice would be related to health care. Like get up and stretch more. Get more cardio.

I haven’t gone back and read Sleeper or even looked at it, not in a long time, but I remember it as a really exciting time. Me and Sean were becoming more and more of a team, and I’d figured out a way to write a superhero/supervillain story that kept me interested. And like you said, it felt small and personal.

We can all identify with the people who aren’t in charge, you know?It was all about the point of view, really. When you start from a good point of view in a big espionage saga, you can bring something different to it. That book showed the sort of working man/soldier aspect of these big organizations, which to me is more interesting than writing about the people in charge. We can all identify with the people who aren’t in charge, you know?

I think that is definitely something I’ve carried over into Criminal and almost everything else we’ve done. Keeping the stories down to earth and personal makes them stand apart, to me, at least.

Aside from your prolific comic book work, you also work in Hollywood—you wrote some of the first season of Westworld and you’re producing a new show. I imagine the process of working on something as intimate as a novel or comic book is starkly different from the idea-fest that I envision in a writers’ room. Can you share some stories from that? Was it tough to adapt to what seems like a mile-a-minute situation?

In some ways, it was definitely tough. It’s a big change to go from working at home all the time to being in a room full of other people all day long. I think my career in comics prepared me pretty well for all the moving parts in television, though, actually. If you’re at all successful in comics, it’s usually because you’re juggling too many projects, like a pulp writer trying to survive in the depression, so writers in comics are taught to compartmentalize things a lot. You’re often writing three or four things at the same time, so bouncing around between episodes of a television show and taking a meeting about a movie idea, and continuing to move forward on another thing… those don’t feel so impossible to accomplish if you wrote for Marvel and DC for a decade or more, you know?

The biggest thing for me was learning when to just shut up and doodle in my notebook and listen to other people’s ideas. I learned a lot about how TV shows are created, on both Westworld and on my own show with Nicolas Refn for Amazon, where I wrote or co-wrote every episode, but one thing I’ve definitely learned is that I would go nuts if I didn’t have my comics career with Sean Phillips.

Just having this outlet to tell stories without anyone getting in the way or giving us notes—even if they’re good notes—is something I’m more and more thankful for every year. It feels very pure, and it allows me to find ideas and stories I didn’t even know I needed to get onto the page, if that makes any sense.

We’ve talked a bit over the years about our shared love for mystery novels past and present—so, I have to ask: have you ever considered writing a prose novel?

Oh sure. I’ve tried a few times, but deadlines have always gotten in the way. I have a few ideas that might work best as prose novels, but we’ll see if I can find the time or talent to pull them off. I’m pretty happy as a writer of crime comics, and that takes a lot of my time, so I won’t make any promises.