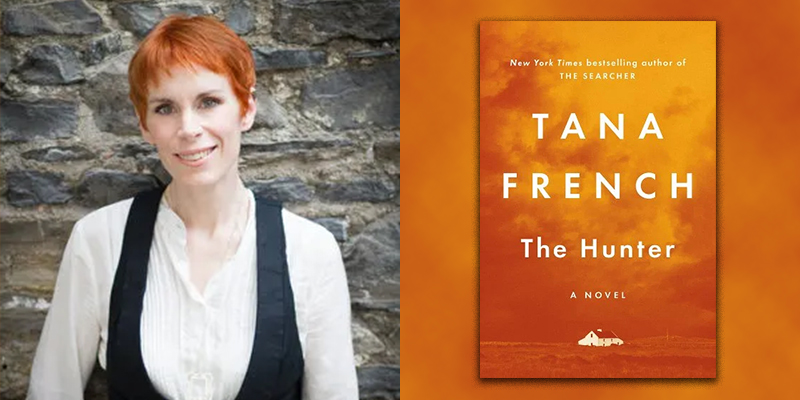

In The Hunter, her ninth novel, Irish-American author Tana French takes us back to the small West Ireland village that she introduced in The Searcher. Retired detective Cal Hooper has made a home in Ardnakelty at the foot of the mountain, away from police cases and the city bustle. It’s a blazing hot summer, and while farmers worry about their crops, Cal’s life seems to have settled in a peaceful groove. His relationship with local Lena is going strong; meanwhile Cal keeps a watchful eye over teenage neighbor Trey, his now trusted carpentry assistant. But Cal’s makeshift family comes under threat when Trey’s father, Johnny, marches back into town with a scheme to find gold on local land and a sleek London millionaire in tow.

Readers jonesing for the tightly plotted procedurals of French’s Dublin Murder Squad series should adjust their expectations. The Hunter, like The Searcher before it, is a slow burn. But it may be French’s best novel yet. The myriad narrative skills the author has honed in her eight previous novels are on full display here, immersing the reader into a deeply atmospheric, character-driven tale. At times poignant and others hilarious, The Hunter delivers a taut, intelligent examination of loyalty, instinct, and community. French masterfully excavates the secrets we keep for love or revenge and explores the lengths we go to to protect our family, be it blood or chosen.

I had the thrill of speaking with Tana French over Zoom. We discussed her characters, her creative process, the ethics of writing the detective as hero, the joys of Irish banter, and much more.

Jenny Bartoy: Where did you get the idea for The Hunter’s premise, about finding gold in Ireland?

Tana French: My last book, The Searcher, was basically mystery software running on western hardware. I’d been reading westerns and thought many of the western tropes would map really well onto the west of Ireland. There’s a lot in common in setting, that sort of wild beauty that demands a lot of physical and mental toughness. And there’s a sense of place that’s so removed from the centers of power, both culturally and geographically, that anyone who wants to create a functioning cohesive society [is] going to have to make their own rules. I felt, when I finished The Searcher, that there were more Western tropes to play with in that west of Ireland setting, and the first one that sprang to mind was the “gold in them thar hills” trope. It doesn’t sound like a very Irish thing, but it’s true what Johnny says in the book: there have been a ton of ancient gold artifacts found in Ireland, and there have been many gold rushes over the centuries. So it didn’t seem like a particularly implausible thing to happen.

Cal and Trey’s relationship at the end of The Searcher got left at quite an interesting point where they have built the foundation of a solid relationship but they haven’t had time for it to set firm. I thought, what would happen if something came in to disrupt this delicate balance? And the obvious thing was Trey’s absent dad, Johnny, who’s been off in London somewhere. He seemed like exactly the kind of guy who would come in with some big get-rich-quick scheme that might or might not be legit. And that just added up with the gold trope.

JB: In The Hunter, instead of a single point-of-view (POV) narrative focused on Cal Hooper’s experience, this book is told in three POVs: Cal, his lover Lena, and his protégé Trey. In the Dublin Murder Squad series, you changed the single narrator in each book. How did this expansion, rather than lateral shift, in narrative perspective change things for you as a storyteller?

TF: That was the scary part with this book because I had never done [multiple points of view] before. But I’ve discovered that as a writer, I’m really only happy when I’m a little bit outside my comfort zone. I like doing things where I feel like I have to learn on the fly and just pick it up as I go along. So this definitely satisfied that instinct! But also it felt like a very different kind of book, in that The Searcher was about one guy’s journey: Cal coming to this little village looking for peace and obviously not really finding it. But The Hunter is about a pseudo family relationship between Cal and Lena and this sort of semi-feral kid whom they’re trying to turn into a good human being. And because it is about this family and the ways in which it comes under threat, when Johnny and his British millionaire and his gold scheme arrive in the townland, the book needed to be from the perspectives of the whole family. It couldn’t just be one person’s POV; it had to be how the three fit into each other, how the dynamic reflected and rippled back between those three people.

TF: That was the scary part with this book because I had never done [multiple points of view] before. But I’ve discovered that as a writer, I’m really only happy when I’m a little bit outside my comfort zone. I like doing things where I feel like I have to learn on the fly and just pick it up as I go along. So this definitely satisfied that instinct! But also it felt like a very different kind of book, in that The Searcher was about one guy’s journey: Cal coming to this little village looking for peace and obviously not really finding it. But The Hunter is about a pseudo family relationship between Cal and Lena and this sort of semi-feral kid whom they’re trying to turn into a good human being. And because it is about this family and the ways in which it comes under threat, when Johnny and his British millionaire and his gold scheme arrive in the townland, the book needed to be from the perspectives of the whole family. It couldn’t just be one person’s POV; it had to be how the three fit into each other, how the dynamic reflected and rippled back between those three people.

JB: Did you enjoy splitting up the narrative perspectives in the end?

TF: It was hugely enjoyable. I had a lot of fun especially writing Trey, because she’s definitely an odd kid. She’s grown up in this village who has no time for her or any of her family. Her father is even less use when he’s there than when he isn’t. Her mother does her best, but she’s basically used up by just keeping everybody alive and functioning. And so Trey has been figuring it out for herself up until Cal and Lena came on the scene. And this has led her to have quite an odd approach to the rest of the village, to morality, to the way she goes about things she wants. And that’s a lot of fun to write. I find that characters are the most fun to write when they’re somehow in transition, when they’re moving from one stage of life to another, from one viewpoint to another. Trey at 15—that’s a hugely transitional point. You’re starting to move away from a child’s perspective where everything is quite black and white, quite single-minded, you’re consumed by one thing at a time, but you can’t really hold multiple poles and nuances and layers in your head at once, towards a more complex, more mature viewpoint. And she does go through that transition basically in the course of the book. And that was one of the most fun things to write.

JB: Cal, Lena, and Trey are somewhat external to the village community. In the first book, this draws them together. But in this one, they’re each drawn out of their comfort zone and toward the village. Doing what must be done forces them out of the boundaries they’ve labored to set for themselves. Did that lead to any surprises for you as their creator?

TF: Yes, along the way, very much so. The Searcher had been about an outsider, but The Hunter is exactly as you say, it’s about people who are on the periphery. They’re not exactly outsiders. They’re not exactly insiders. Lena by her own choice has cut herself off from the village to some extent, as much as she can; Trey because she’s from this family that nobody even wants to acknowledge; and Cal because he just moved there a few years ago. But they’re not really outsiders, in that they are a part of this network of relationships that’s within the village. And that’s kind of a powerful place to be, because you’re not bound by the place’s rules in the way that a full insider would be. You’re not under an obligation to it, you don’t feel the pressure in the same way. But you do have a certain amount of influence, a certain amount of power, and at different points in the book, they all choose to use that power in very different ways.

But for Lena in particular, it came with surprises. My editor is a genius and started asking questions about Lena’s perspective. And I suddenly went, oh my God, Lena is going to be blown away and delighted and proud and conflicted about the fact that Trey is basically giving the finger to everything about this place in a way that Lena herself never found an opportunity to do. So that’s going to be huge for her. I went back and reshaped it all with this in mind for her.

JB: You get to flex your comedy chops in this book. There’s always humor in your books but this one had some hilarious one-liners and laugh-out-loud exchanges in the pub. Is humor a natural kind of writing for you, or more technical? And what kind of research did you do to write these scenes so convincingly?

TF: Oh, I had to make a huge sacrifice for this kind of prep, of going to the pub! The Irish wit and humor and quick banter—I know this is a cliché; I know that Ireland has a reputation for this, but it is true. It’s one of the major currencies. Here the ability to go quickfire back and forth with your friends shows everything from hierarchy to affection to conflict. Everything is filtered through this lens of humor. That’s how they say, “I love you, man.” The operational mode for everyone in these settings is just to slag each other and throw these lines back and forth in this fast game of squash. So it was huge fun to write, because if you’ve been down the pub a bunch of times and if you have these rhythms and this humor in your head, you can just hit “play” mentally on those characters and let them keep going.

JB: It was great fun to have these humorous breaks amid heavier themes. Your novels feature complex, psychologically astute plots. They tend to rely on characters’ impulses, instincts, and empathy and involve so many twists and turns. What is your process for plotting? How do you organize your writing?

TF: Organization is, anyone who knows me will tell you, my weak point. I’m not good at this stuff. But I am good, I think, at characters. I come from an acting background. So for me, the natural thing is to see characters as three-dimensional as possible and to try to bring the reader to the point where they’re seeing this world through the characters’ fears and needs and biases and objectives. So that’s where I start from. I know there are writers who don’t work like this—I have friends who have every chapter plotted out and every beat mark before they start writing. But for me all the action springs from character, so it means that I can’t really structure in advance. I need to get to know the characters a bit before I understand their interactions and their dynamics. So I start with a basic premise, a main character, and a setting. And I kind of dive in and write for a while and things sort of develop like a Polaroid as I go. And this makes for a lot of rewriting, but it is the only way that works for me. And I kind of hope that because stuff has taken me by surprise all the time—like, I’ll be two thirds of the way to a book and go, oh my God, that’s who did the murder!—I hope some of that [spontaneity] comes across to the reader, the sense of things coming out organically.

JB: Yes, it definitely does! Many books, TV shows, and films that historically have glorified police work are now turning more critical or at least nuanced. Has that trend affected your approach in writing crime novels?

I think the mystery genre needed to start questioning that whole viewpoint that the detective is intrinsically heroic.

TF: I definitely think that it’s a good movement within the mystery genre, to acknowledge that the detective’s point of view is not the only one, and is not necessarily the crucial one, and is not necessarily the heroic one. Because that’s, of course, where the genre started to a large extent—the detective as a hero who will reimpose order on society after the chaos caused by murder, and that detective is on the side of truth and justice. And many of those books are great, they’re wonderful. But I think the mystery genre needed to start questioning that whole viewpoint that the detective is intrinsically heroic. There have always been flawed detectives, with the bottle of whiskey in the drawer and the ex-wife who hates him and the tortured past, but that’s a different thing. That’s a detective being flawed, but the role’s still being heroic. And I think it’s only recently that there’s more of a drive towards the idea that the role itself is flawed and is dangerous, and is not intrinsically heroic, and comes with dangers built in.

In The Witch Elm, that was one of the things I really wanted to do, because I realized that my first six books were all from the detective’s point of view. It was all about seeing the investigation from the perspective of somebody for whom it was a source of power, and a source of triumph, and a source of reimposing order. And that is not the only or the most important viewpoint in any investigation. There are also people for whom this is not a source of power, or of reordering the world, it is the opposite. It’s having your power taken away from you, having your life overturned, having everything smashed around you in ways that you may never be able to reconstruct. In The Witch Elm, the narrator tries at one point kind of pathetically to be the detective, but he’s also the victim, the suspect, the witness, all of those other viewpoints I thought were just as important and needed a voice.

In The Searcher and The Hunter, Carl is a retired detective. He’s taking early retirement from Chicago PD, for that reason. In The Searcher, he says something about having realized that one of them, either he or the job, or both, cannot be trusted. And he doesn’t know which it is. He’s left the job behind and is trying to reject the whole notion of himself as detective when that is suddenly demanded of him again, and then it becomes a kind of crisis of conscience. And it’s the same here in The Hunter where people want to position him as a detective, as not a detective, as a tool for detectives, or as a tool against detectives. Being on that side of the law has become a much more complex thing, within the mystery genre. I think this was not just good, but really necessary to examine the moral complexity not of the individual character, but of the entire concept of detecting.

JB: I do feel like we’re getting more variety in literary crime fiction, which is exciting. On a related note, you’ve previously written about cops on the job, but in these latest novels, as noted, Cal is retired. What kind of challenges do you encounter in writing mysteries when the sleuth doesn’t have access to institutional resources?

TF: That was actually one of the most fun things about writing both The Searcher and The Hunter. Because I was trying to reexamine, what is it morally, mentally, emotionally to be a detective? What does it mean to people? And Cal is in this position where all those trappings have been stripped away. At several points in both books he’s going, if I were still on the job, I could have somebody dump this person’s phone, I could track this, I could pull info on every single suspected witness I’ve got, I could look at the forensics, and now I have nothing. So is he still a cop? Does he even want to still be a cop without any of the accoutrements, without any of the artillery, that are in a cop’s armory? He has none of that. But he still does have whatever instincts and skills he’s built up on the job. And that isn’t actually something he wants to have, he was trying to leave all that behind.

That was the most interesting part of writing it, because on a technical level, it means he just goes and talks to people, and he can do it in slightly more subtle ways, he has a little bit more experience questioning people. But what’s the relationship between the individual and his sense of himself as detective? That becomes core to it. And that was one of the reasons I wrote a retired cop, rather than one that was still on the job and having doubts, which would also have been interesting. Because, with all the physical trappings stripped away, you get to see the direct relationship between him as an individual and what’s left of the detective in him—what are the tensions between those things?

JB: I noticed that you avoid digital technology in this novel. Your characters mention Netflix and TikTok in passing, and they use phones sporadically, but they’re not googling for evidence or going down Facebook rabbit holes. Tell me about this narrative choice.

TF: Technology is really boring to write about! There are some writers who can make conversations via text message leap off the page and make them vivid and interesting, but I like characters being face to face. And so luckily, with the characters I’ve got, that was actually a fairly natural choice, because these are people in a milieu where they’re going to go see each other. They’re going to talk face to face. Trey in particular doesn’t have a phone yet at this stage because her mother hasn’t been able to afford to buy one. So that made it much easier to go, alright, the main form of communication is not going to be phones and email. They’re living in a place where people assume that if you want to talk to somebody, you’re probably going to meet them down the pub. And I thought that technology would have gotten in the way of the character interactions.

I’m worried about this, because I know that more and more interaction is, in fact, on screen and via text. What do I do? Do I go with that and try to find a way to make it interesting, or am I going to keep dodging Snapchat for the rest of my career? I’m not sure. So far I’m just dodging Snapchat, everybody’s just going to go meet up! So much of our interactions is when you look at somebody, when you see their movements, when you listen to the tone of their voice, when you catch the tiny nuances. So much nuance lies in the face to face. And I think real-life interaction is being impoverished by the fact that less and less face-to-face interaction happens. But I’m not going to do it in my books, because it would impoverish them too.

JB: Your novels make beautiful use of setting, almost as a character. In The Searcher the mountain felt alive. Here in The Hunter, it’s the weather, oppressively hot with an apocalyptic sort of overtone, but also the townland which acts and reacts as a cohesive unit. How do you approach setting and atmosphere as narrative elements?

TH: The Hunter in particular, but The Searcher as well, are very different from my earlier books, because the early ones are set in cities. And these two are rural, many of the characters are farmers. So for them, the land and the heat wave in The Hunter aren’t just atmosphere, these are crucial practical things that alter their lives on a very concrete level. The heat wave isn’t just, oh my god, it’s boiling, let’s go to the park and get ice cream—it’s a threat to their livelihoods. A heat wave like that messes with your feed for the winter; it messes with next year’s lamb crop. It has a knock-on effect in farming that lasts a long time and can threaten the farm’s very existence. This puts a lot of the characters in a position where they’re willing to listen to Johnny’s get-rich-quick scheme, which normally they wouldn’t have even given him the time of day. Normally they’d have laughed him out of the pub with that nonsense. But they’re made vulnerable by this heat wave. So the weather and the land and the terrain aren’t just setting and atmosphere; they play a solid role in the plot.

JB: In The Searcher, Trey longed for the brother who’d disappeared. Here in The Hunter Trey wishes her father, who’s reappeared, would go away—sort of an opposite desire. Trey’s preference for estrangement feels so realistic. Family estrangement is a reality—and a choice—for many, but it remains taboo culturally. Reconciliation is usually encouraged or expected, and this trope shows up a lot in books, movies, TV. How did you navigate these difficult family dynamics without making Trey petulant?

“There are situations where the only closure is via division, via literally closing that door forever.”

TF: There is this expectation that closure or a happy ending must involve reconciliation in some way with your blood family. And I think it’s ridiculous, because that’s not how the reality works. There are situations where the only closure is via division, via literally closing that door forever. And there are situations where reconciliation would do more damage than healing. I had to be very careful so it didn’t just seem like a teenager going, well, my dad went off and left us, now he can get stuffed if he thinks he’s walking back into my life — which at the beginning of the book, there is a certain element of that, to the point where Trey blames Johnny for her brother’s loss. But gradually, that sense deepens, the more she gets to know him, the more mature and in-depth and complex that need to separate herself from him becomes. And she reaches a point where she’s only willing to maintain that connection, because she needs it in order to effect another form of revenge.

She comes to the realization that her real family unit doesn’t in fact include Johnny in any way. She’s constructed her own family unit with Cal and Lena, and in other ways with her mother and siblings. And I thought that was a much more realistic and nuanced take on things than just going, well, he’s blood, you must all be happy ever after, or in some way, damaged by the loss. Because frankly, I don’t think Trey is damaged by her father being out of her life. She may be traumatized by the things he did along the way, but she’s not traumatized by him being gone because she, as an individual, has made her choices and constructed her family unit. And that is what I hope saves her from being a petulant teenager going, I hate you. This is coming from strongly thought-through choices, and from sacrifices that she’s been willing to make for this new sort of family.

JB: Before we sign off, I have to ask: what’s next for you?

TF: Well, to my deep surprise, this seems to be turning out to be a trilogy, which is just not what I thought. I thought The Searcher was a standalone! But it doesn’t feel like either the character arcs or the thematic arcs are really complete. So it seems like I’m writing the third in a trilogy about this village, and these people, and all the layers and stories and tensions and dynamics stored up there. I didn’t expect that. I’m always worried because I don’t plan in advance—what if I dive in there and there’s no book and the threads never tie up? But fingers crossed. It’s always been okay so far.