When my husband and I decided to get married and have kids, we imagined we’d have boys—probably two. There were very few girls on my husband’s side so there was some logic to this. At the ultrasound, we were both shocked. Twice. A girl, and two years later, a girl. My husband’s reaction to this news looked like grief. He had imagined little men in his image. For me, the phrase “it’s a girl!” initiated a panic inducing list of personally experienced horrors: self-hatred, depression, anxiety, body shame, predatory men, mean girls, predatory men.

I let my list of horrors run riot long after my husband had tamed his. I thought, Girls aren’t born to suffocate, but eventually, they absolutely fucking do. They’ll drown trying to hide their strengths and their weaknesses! Girls are poked and prodded and ogled and used to build bonds between less secure women—“God she’s weird”, “Did you see her ass?”, “I don’t mean to be awful, but what is she thinking?”; (let me tell you a secret: we know when we are being awful)–and fuck me, but one in five women experience sexual assault; women are more likely than men to attempt suicide; 8.6 women will have an eating disorder in their lifetime; and lets not even talk about body dysmorphia; and did raising girls mean I had to live through it all again? Twice?! The rush of things I would have to navigate alongside my girls was worse than any slasher movie I’d ever sat through and to top it all off I was filled with shame. I had no idea my own misogyny ran so deep.

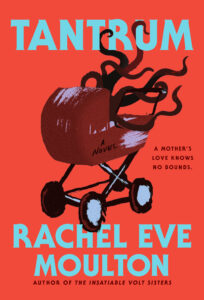

Thea, my protagonist in TANTRUM, is the mother of three kids under ten—two boys and a girl. Lucia, her easiest pregnancy by far, is proving to be the most difficult to raise. Her literal hunger terrifies Thea. And this is what I wanted to explore—the way women are taught to swallow and silence their trauma. We are fooled into thinking that staying quiet about the wrongs done to us will keep them from touching our children. The very idea that female hunger is dangerous—even Thea, Lucia’s mother, fears her daughter more than she loves her. Thea, the reader finds out, has a mother who has taught her that burying her ugly truths will make them go away. It’s a lie of course. Trauma lives in the body, thrives in the quiet dark. It takes the birth of Thea’s truly monstrous daughter to push Thea into confronting her past.

For those of us who are parents or play the role of a parent, we know that watching a child grow gives you a new perspective on who you were at every age. I, for one, felt every bit an adult when my second-grade teacher told me I was “stupid” for reading my favorite book more than once. I adored this teacher and was ashamed to have disappointed her. I told no one what she said. When my daughter’s elementary school teacher suggested she was stupid, I realized how absurd it was for little me to have taken that moment and handled it all on my own. Now, the realities of Thea’s childhood are far harsher than mine, but shame kept secret is powerful in every form. I want my daughters, my readers, to dive headfirst into the question: How do we process the violence of womanhood?

And this is the beauty of horror in 2025. I think all women should watch The Babadook and Strange Darling and The Substance, to name just a few, because women (cis or trans) are not just beautiful victims. We are terrified mothers and self-loathing actors. We are the perpetrators—the ones to fear. Modern-day horror gives women dimension in a way that we’ve been denied.

And it isn’t just men denying us this experience. We deny it for ourselves, for each other. As an example, there are three basic responses you will get from women when you say you write horror. The first: “Oh my gosh! I love horror.” The second: “Horror? That’s too bad. I can’t read that stuff.” The latter is said without shame, as if the wide sweep of a phrase like “that stuff” would ever be applied to another group or activity without offense. A slight variation on this second one is, “I used to love horror, but now that I’ve had kids, I just can’t stomach that stuff anymore.” I take particular umbrage with this last one. It seems an indication that women are happy to lack agency when it comes to tapping into their darker histories, their current realities.

I should admit that I was the middle school girl who hated “that stuff.” I left the slumber party early just so I wouldn’t have to watch whatever terror was going up on the television at midnight. And in my defense, back then, horror didn’t feel like it was made for me. I couldn’t quite understand where I, a competent Midwestern girl, fit into the narrative. Wasn’t it all just about women actively being punished for their social misconduct or being so surprised by a totally predictable plot twists that all they could contribute was a blistering scream? Most women already know how dangerous the male gaze is. We don’t need to be told it via a horror movie. In Psycho and Carrie—two movies I’ve also come to love–it is clear from the first beats of the film that the camera is male. After all, female trauma is well worth monetizing if it turns on a male audience, right? Who knew tampons and knives could be weaponized in such sexy ways!

I’d read “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson and The Haunting of Hill House in high school. In college I found Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Cat’s Eye, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, and Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love, all of which were the kind of horror that rang true for me. Still, there was a serious lack of female writers in horror sections—the above were rarely found on that shelf. I wasn’t aiming to be a horror writer by any means, so when I saw Ginger Snaps the Canadian werewolf movie, directed by a man but written by a woman, on the floor of a friend of a friend’s apartment. I was smitten. The movie, about Brigitte and Ginger, was the first time I’d seen menstruation depicted in a movie. It was also the first time that I’d realized how intrinsically female werewolves are—creatures that change form and become more aggressively powerful once a month. Good god. Why wasn’t every werewolf in every movie ever female?

My eldest loves movies. And since her birth in 2009, there has been a magnificent rise in female directed and female led horror. We watch horror movies together now, and I love how a conversation about one leads to the next. Ginger Snaps to Jennifer’s Body to Midsommar to The Babadook to The Substance. And on to novels like Night Bitch by Rachel Yoder and Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth.

Writing Tantrum was a way for me to confront my own misogyny. To voice all the rage and look at what it made. My girls have made me a stronger woman—raising them and watching them grow has empowered me.

I like to tell my daughters that if something brings you shame, you need to find someone to tell that story to straight away. Shame is most dangerous when it remains untreated, unvoiced. Like black mold it needs a dark, dank, humid environment where no one sees it. As soon as you speak it, write it down, film it, the story of that shame disperses into screams and even laughter. The blood bath of it all is your weapon, girls. Use it. Beat back the hate by finding other trusted people to share it with. Never shy away from the female experience. Look right at it. Give birth to it if you want to. The gore is a means to a beautiful end.

***