Science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke said that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” I’m not sure I fully buy that—my cell phone is pretty advanced, and yet, when I access the internet on it to double-check this quotation, I don’t feel like I am doing a spell. It might look impressive, but I’m pretty sure no one working at Apple is an actual wizard, and I don’t imagine any of my contemporaries would mistake what I was doing for magic.

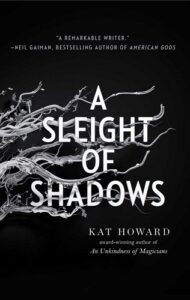

Still, it’s pretty clear that we are living in a technologically advanced world, so much so that things that might have once looked magical, or even miraculous, are now quotidian. One might even wonder why a fictional fantasy world still needs magic, when technology can do so much. But my latest book, A Sleight of Shadows, takes place in the modern world and is a book about magic, about people who are actual magicians.

In fact, living in the modern world causes some of these magicians to consider what kind of magic continues to be important, when so much can be done by technology. In the Unseen World, the traditional first spell taught is the one that will light a candle. But what is the point of that, in a world where you can light an entire room by flicking a switch, or programming a smart appliance? Even if you prefer candlelight, there are easier ways than dealing with magic and the consequences that the use of magic has: I light my candles with a device that charges via USB port, and turns on by pressing a button. (Though I do keep old school matches in case of power outage.) If it’s that easy, why not start with a different spell, teach the new magicians something that can only be done by magic, something actually useful for them?

Here’s the thing. I am deeply grateful for the ways in which technology makes my life easier. I am extremely glad that I can do laundry with the press of a button, that I don’t have to grind the beans for my coffee by hand, and that my phone is a mini-computer. But I love magic. So when I think of a world where the fantastic (defined loosely, so as to include things that are currently impossible being done by either science fictional or magical means) happens, I’m pretty much going to pick magic over technology every time.

That choice can often be simply the matter of author preference—do you want to poison someone by a potion mixed in a cauldron or by genetically engineered bacteria? Either way, the character is dead after drinking whatever you put in their glass. If the fact of the death of the character is what’s most important, then just choose your weapon.

But for what I wanted to do in my Unseen World books—An Unkindness of Magicians and A Sleight of Shadows—I needed the fantastical element to be magical in nature. I wanted to talk about the consequences of using magic, and I wanted to make those consequences visceral. I needed the magic to be literally embodied in the magicians. The piece of the story I was interested in wasn’t what the fantastic element did, so much as it was how the fantastic was done.

There is a magician in the first book (spoiler alert if you haven’t read An Unkindness of Magicians) who is losing his magic. For various reasons, he’s afraid to let anyone else know that this is happening, and so he uses technology to cover up his loss. For a while, it even works—these are magicians who can encode spells into text messages, so there’s no inherent fear or distrust of technology. For them, it’s just another tool, one that it’s not strange to see him using.

But even sufficiently advanced technology cannot fully replace magic in the Unseen World, and this character’s deception is revealed. And that was a deliberate choice on my part as well—I wanted to show that living in a high-tech world didn’t erase the need for magic. Or, more importantly, the desire for it. The magicians of the Unseen World are almost universally wealthy and powerful. But the thing that matters most—the thing they kill each other over—is the power that magic gives them.

Technology is the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes. An important thing to remember is that even the matches that I light my candles with when the power goes out are also an example of technology. They’ve been around long enough now that they no longer seem cutting edge (the first successful friction match was invented in 1826 by the English chemist, John Walker, but there are historical records from China describing the use of sulfur matches as early as 577), but they are still, according to the above definition, technology. They might even, at one time, have appeared magical.

But there is a reason why, in the Unseen World, that even though the technology exists, and lighting a candle with a match is easier, learning how to do magic begins with learning the spell that lights a candle. Magic’s existence, and its hows, still matter, and they’re still worth telling a story about.

***