In 2004, following allegations of widespread inter-governmental spying at the United Nations headquarters in New York, then Spanish ambassador to the U.N., Inocencio F. Arias, told the Washington Post: “In my opinion everybody spies on everybody, and when there’s a crisis, big countries spy a lot.”

Despite the delicious irony of Señor Arias’ first name, he was right to point out that no government is innocent of espionage; they’re all doing it, and they’re all denying it. To us regular citizens, there’s an inherent absurdity here: why go through the rigmarole of denying you’re doing something that everyone knows everyone’s doing?

As I write, NORAD has spotted the third—scratch that—fourth unidentified object in a week flying over U.S. and/or Canadian airspace. When the first one was shot down by the U.S. military and declared a Chinese surveillance device, Beijing made the bizarre claim that it was a “civilian airship” used for “mainly meteorological” purposes. The entire company of people who believe this claptrap could hold their annual convention in a weather balloon.

In late 2016, U.S diplomats posted to Cuba reported the first known cases of so-called Havana Syndrome, including loud noises, headaches, nosebleeds and dizziness. The Cuban government denied any involvement but, after examining some of the early victims, the University of Pennsylvania concluded the symptoms were real (not hysteria) and amounted to a brain injury similar to concussion.

In 2018, Sergei Skripal—a former Russian intelligence officer who acted as a double agent for the UK and subsequently settled there—was almost killed in a novichok poisoning, along with his daughter, near his home in Salisbury. British police used CCTV to identify the suspects: two officers from GRU (Russian military intelligence). Russia Today broadcast a ludicrous interview in which the perpetrators announced with straight faces that they had visited the “wonderful” city of Salisbury to see its world-famous cathedral, noting that the spire is 123 meters high. Top marks for research.

The British government’s response to this hogwash was that the denial was “risible”. As a former British official working on national security, let me translate that for you: Her Majesty’s government was apoplectic with rage.

Incredibly, these stories are a long way short of the heights of spy-related absurdity. For that, one needs to investigate the ways in which real-life espionage has been influenced by spy fiction. My nomination for the king of that particular castle is James Grady’s terrific 1974 debut, Six Days of the Condor.

In the early 1970s, Grady was a twenty-something congressional staffer from Montana with zero national security experience. His debut novel follows Ronald Malcolm, a lowly and bored C.I.A. analyst working at a small office in Washington, D.C., with the cover name the American Literary Historical Society. In fact, the office is part of the C.I.A.’s information division tasked with scouring literary works to find useful ideas or leaked secrets. When all Malcolm’s colleagues are suddenly murdered, he goes on the run. He kidnaps a paralegal named Wendy Ross and hides out in her apartment while trying to work out who wants him dead and why.

In 1975, the movie Three Days of the Condor shortened the timeline and moved the action to New York, apparently at the request of star Robert Redford. We D.C.-based writers are perhaps entitled to be peeved that one of the most iconic espionage stories set in the capital was filmed in New York, but nevertheless the movie was a hit, seen widely in the U.S. and around the world.

Hold that thought and jump forward five years to 1980. David Belfield was a security guard from Long Island who converted to Islam, changed his name to Daoud Salahuddin and was working at the Iranian interests section of the Algerian embassy in Washington, D.C. On a July morning, dressed as a mailman, he drove a postal service jeep to the Bethesda, Maryland, home of Ali Akbar Tabatabai, an Iranian dissident.

According to the Washington Post, Salahuddin was carrying two envelopes. The top envelope contained a special delivery form for Tabatabai to sign; the lower envelope contained Salahuddin’s hand, wrapped around a 9mm pistol. He rang the doorbell and shot Tabatabai three times, causing mortal wounds. He then fled via Canada and Geneva to Tehran, where he has lived ever since.

One of the remarkable things about this murder is that it closely mirrors a scene from Grady’s novel. The rogue C.I.A. unit hunting Malcolm sends an assassin to Wendy Ross’s apartment dressed as a mailman. He gains access to the apartment by insisting that Malcolm needs to sign for special delivery. He attempts to shoot Malcolm who, unlike the unfortunate Tabatabai, survives the ordeal.

Newsweek reported that Grady, shocked about the similarity between his mailman scene and the murder of Tabatabai, later had the chance to talk to Salahuddin on the telephone from Tehran. The murderer said he might have seen Three Days of the Condor, but couldn’t remember. He thought it more likely that the idea to pose as a mailman had come from a friend who had seen the movie.

This is not the only time Grady’s debut has influenced real-life espionage; the other example is even more shocking.

In 2007, D.C. writer Pete Earley published a fascinating nonfiction book titled Comrade J: The Untold Secrets of Russia’s Master Spy in America After the Cold War. Earley tells the previously unheard story of Sergei Tretyakov, the former deputy head in the New York office of the SVR, the successor to the overseas branch of the KGB. In 2000, after serving in this role for about five years, Tretyakov suddenly disappeared and was subsequently granted asylum in the U.S.

Comrade J is full of fascinating secrets that Tretyakov told Earley about his time as one of Russia’s most senior spies. It includes the story of his first job in espionage, working at a Moscow office with the gibberish name All-Union Scientific Research Institute of Systems Analysis. In fact, Tretyakov had joined the NIIRP, i.e. the Scientific Research Institute of Intelligence Problems of the First Chief Directorate of the KGB.

Tretyakov tells Earley that he joined the KGB because he wanted action; he longed to be like James Bond and expected the KGB to provide that sort of excitement. So he found his first assignment at the NIIRP boring and disappointing. Why? Because the principal role of the NIIRP was to sift through newspapers and magazines from all over the world looking for useful information to share with higher ups.

Sound familiar? Tretyakov explains that several KGB generals had seen Three Days of the Condor and had concluded—based on the entirely fictional American Literary Historical Society invented by James Grady—that the U.S. was spending much more effort and money on analysis than was the KGB. Hence, the NIIRP was born.

An incredible story, but apparently true.

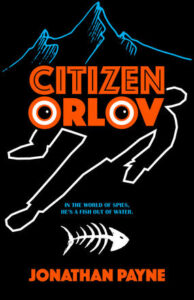

My debut novel, Citizen Orlov, is set in the unnamed capital city of an unnamed country in central Europe, at the end of the Great War. It tells the story of an unassuming, working-class fishmonger who innocently answers a telephone call meant for a government agent and finds himself embroiled in a covert plot to assassinate the head of state.

When Orlov realizes that his life and the lives of his mother and friends are in danger, he sets out to learn some basic spycraft in order to take on the plotters at their own game. Much to his own surprise, he becomes a significant player in his country’s fledgling national security apparatus.

Some early readers and reviewers have called Citizen Orlov a spoof, but I wonder whether that’s the right word. When you consider the utter absurdity of real-world espionage, does this plot really sound so unbelievable?

***