The term antidetective generally refers to a category of stories that utilize, and then subvert, the conventions of a detective novel. These are stories that induce the desire to detect but often frustrate that impulse in various ways, casting doubt—not on the capability of the central detective figure—but on the methodology of detection itself. Antidetectives, a cousin of the metaphysical detective (books that use detective conventions to approach questions of knowing and being) exist on a spectrum of uncertainty; sometimes the investigations don’t solve; sometimes they do, but something else—like the narrative—breaks apart. Sometimes all investigation into the initiating crime peters out, or it becomes increasingly unclear if there ever was a crime in the first place. I have always been drawn to these kinds of books, but the internet likely increased this general leaning. It used to be that one could find things on the internet: new bands, who your ex was now dating, the history of the silk trade. Knowledge—complete and total—felt accessible, possible if you were willing to look long enough. And yet even before Google became mostly useless, there was always a snake-eating-its-own-tail aspect about it. After a certain amount of clicking, it was hard to feel as the place I was headed had much to do with truth or understanding.

The advent (and the heyday) of the antidetective mostly came before internet as we know it now, but the relationship between the two is something I thought about often writing my own novel, Swallow the Ghost, which sets us down into the life of Jane Murphy, a social media marketer who has created a viral internet mystery using different social media accounts. Jane’s occupation—a person actively working to harness the attention of internet users—immediately troubles the idea that investigation, at least on the internet, will ever be a purely truth-seeking experience. But as the violence skips over and out of the virtual realm and into her physical world, questions about detection and investigation persist, casting a shadow over the relationship between knowledge and understanding.

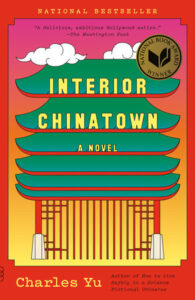

Below, in no particular order, is a sampling of the antidetective genre as I broadly define it. If you are looking to dip your toes in the water before picking up a novel, might I suggest these short stories: Ryūnosuke Akutagawa’s story, In a Bamboo Grove, The Enigma, by John Fowles, Death and the Compass, by Jorge Luis Borges, and Opa-Locka, by Laura van den Berg. Included below is also Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown, something that I think of as more recent subgenre of the original antidetective and that I first saw in Carmen Maria Machado’s novella, Especially Heinous: 272 Views of Law & Order SVU. These kinds of stories don’t induce the desire to detect necessarily—but they keep the procedural (or the crime novel) as the putative dominant structure on which the story hangs. In other words, procedure is everywhere. For the characters, it’s the climate. There is nothing else.

The Investigation, by Stanislaw Lem (translated by Adele Milch)

In London, corpses have begun moving slightly and then disappearing altogether. The book begins typically: the Chief Inspector gathers together a cadre of officers and consultants to analyze the case. Then, under the direction of Lieutenant Gregory of Scotland Yard—who lives in one of the strangest houses I’ve ever seen described in literature—the case proceeds in a more atypical direction. Later conversations amongst the investigators include statements like “[t]he kind of criminal you’re talking about doesn’t exist and couldn’t possibly exist.” The Investigation is the famous science fiction writer’s take on the procedural, and a book of which he has said he received many angry letters after writing.

The New York Trilogy, by Paul Auster

Quinn, a former poet and current writer of mystery novels, is the recipient of a late-at-night wrong number: a woman, looking for the detective Paul Auster (yes, that Paul Auster). For reasons he does not care to analyze, Quinn takes the case. Though he approaches the work with a robust understanding of all things detective, his investigation quickly goes sidewise: “The question is the story itself, and whether or not it means anything is not for the story to tell.” A classic of the genre, and a book that changed my young life. I had read the Trilogy—for the umpteenth time—very shortly before Auster’s death this year and so I felt as if I had just spent time with him before he passed. A lucky feeling indeed.

Reflex and Bone Structure, by Clarence Major

Cora Hull, a Greenwich Village actress and her lover are killed in an explosion. Was she killed due to her membership in a “revolutionary Black group,” or with a “militant white group,” or because she was “branching out into the women’s liberation movement?” Or was it a suicide? Did Canada kill her? Written in 1975, Reflex and Bone Structure merges high modernist fragmentation, surrealism, and metafiction in a book where it’s frequently possible to lose one’s footing in the middle of sentence. “I simply refuse to go into details. Fragments can be all we have. To make whole”—the narrator states, and he is not kidding, because Major is a writer who is concerned with how technique informs and forms the message. (If you like the level of surrealism and instability in Reflex and Bone Structure, you might like Rip-off Red, Girl Detective, by Kathy Acker. Some would argue that the detective genre is often rather sexless. Not in Acker’s hands, who makes text (and then some, she once described is a “pornographic mystery”) of the erotic subtext humming under most noir. Sex is complicated though, and this isn’t your Marlowe’s sex life. TW: SA/ incest.

Death in her Hands, by Ottessa Moshfegh

A seventy-two year old widow, Vesta, comes across a note in the forest: “Her name was Magda. Nobody will ever know who killed her. It wasn’t me. Here is her dead body.” Except there is no dead body, and Vesta becomes obsessed with Magda, both her life and her death. What this means for an amateur detective with zero clues and zero friends excepting her dog, I won’t lay out in detail but, suffice it to say, she does not proceed a la Sherlock Holmes. Vesta is a fascinating, prickly, mystery of a protagonist, and Death in Her Hands, is a truly moving novel about the loneliness of an elderly woman unmoored at the end of her life.

The Name of the Rose, by Umberto Eco

In a questionable translation of a missing manuscript, Adso of Melk, recalls the time he spent in a fourteenth-century monastery with Brother William, the Sherlock Holmes to his Watson. Monks are dying, and a power struggle is raging, involving the Emperor, the Pope, those Irish twins of the Catholic Church—the Franciscans and the Dominicans—as well as a handful of heresiarchs and a couple librarians. On the spectrum of antidetectives, it’s not a bad place to start as it offers a bit more closure than others. Then again, our Franciscan Sherlock has the occasion to say: “Perhaps the mission of those who love mankind is to make people laugh at the truth, to make truth laugh, because the only truth lies in learning to free ourselves from insane passion for the truth.” (If you like The Name of the Rose, you might also like A Wild Sheep’s Chase by Haruki Murakami. That Awful Mess on Via Meruluna is not very much like The Name of the Rose, but it is another classic written by another Italian author, Carlo Emilio Gadda, which is also translated by William Weaver).

The Taiga Sydrome, by Christine Rivera Garcia

A woman (an ex-detective with many failures) is hired by a man to find his lover who abandoned him, fleeing with another into the “taiga,” a hostile forest at the ends of the earth. The detective and her translator arrive in the taiga, where they meet a wolf, a feral child, a capitalist, and a group of lumberjacks. Part detective story, part fairy tale, part a thing only CRG could think up, The Taiga Syndrome is an affecting book about the end of love and contains some of my favorite sentences (as translated by Jill Levine and Aviva Kana): “Look at this: your knees. They are used for kneeling upon reality and also crawling, terrified.” (Lydia Davis’ The End of the Story is a different kind of antidetective about the end of a relationship, I would argue, and I would recommend).

Interior Chinatown, by Charles Yu

Willis Wu is playing Generic Asian Man in a procedural called Black & White. Action lines in the screenplay tell us “Dead Asian guy is dead.” Also, there’s an Older Brother who has gone missing. Does this case solve? Well, there is a trial, and it’s certainly an investigation. In Pynchon’s classic antidetective, The Crying of Lot 49, the protagonist Oedipa Maas notes: “The act of metaphor was a thrust at truth and a lie, depending where you were: inside safe, or outside lost.” But Yu’s novel reminds us of the limits of binary thinking; one is not always safe, even if they are inside the metaphor. Both inside and outside, then, the protagonist looks at his daughter as she plays; he thinks “[w]atching her is like finding old letters, of things you knew thirty years ago and haven’t thought of since. How to feel, how to be yourself. Not how to perform or act. How to be.” (Try also, also Especially Heinous by Carmen Maria Machado and Brooklyn Crime Novel, by Jonathan Lethem).

***