I had never met the two stern-looking young women sitting across from me in the train car, but I knew who they were. Both were wearing in vintage dresses, pressed and perfect, their hair waved and smooth in the style of the 30’s. The train, too, seemed to be old; the seats were wooden, and the car jostled terribly, causing a constant swaying and jerking motion that was relentless.

“You,” one of the women said, pointing her finger harshly at me, “did not do us justice.”

In agreement, her companion slowly shook her head.

“It’s not that simple,” I tried to say, but the woman with the pointed finger narrowed her eyes in anger.

“You could have helped us,” she said sharply. “And you did nothing.”

“That’s not true,” I started to argue. “I do want to help you.”

“You let her off the hook,” the other woman, who had been silent up until now, said. “And she killed us.”

“She got away with it all over again,” the first woman said. “And we still can’t do anything about it. We thought you would fix that.”

I was humiliated. I felt an icy sheet of shame frost over me, as if I had been caught doing something horrible. These two women, Anne LeRoi, the bolder one, and her quieter companion, Sammy Samuelson, were murdered on the night of October 16, 1931. They were killed by their best friend, Winnie Ruth Judd, known as Ruth, each with a precise gunshot to the head. Both women were stuffed into trunks, Anne whole, Sammy dismembered, and loaded into the baggage compartment of a train travelling across the dry, brittle desert between Phoenix and Los Angeles.

Their bodies were discovered as blood leaked onto the platform of the Los Angeles Union Station, alerting porters that something awful was inside each trunk.

I didn’t wake up as much as I shot into in the darkness of my bedroom, feeling that Anne and Sammy had been right there. That dream followed me for days. It still bothers me.

In 2015, I went into the Arizona State Archives to research the case convinced that Ruth acted in self-defense, which was the lore that had followed the case around since 1931. She mourned for her dead friends for the rest of her life, referring to the crime as “my tragedy.” In Arizona, Ruth was held up as the patron saint of injustice, convicted of a crime and sentenced to hang for a misunderstood accident.

Ruth was breathtaking, and not just in the beholder’s eyes. She was a great beauty with kind eyes, a lovely smile and was always perfectly coiffed. On the day she surrendered—after five days on the run with barely any food, water and a bullet lodged in her hand that was turning gangrenous—she emerged in a fur coat, flawless finger-waved hair and a veil of sadness, a police officer flanking each arm. The coat was stolen, but everything else about her was perfect. Not a hair out of place or a tint of lipstick. She looked miraculous and ethereal, like a saint. The photo looked like a movie still.

Killers don’t look like that, I remember thinking as I studied the photos. They are messy and cold, with twisted mouths and steel eyes. Aileen Wuornos. Griselda Blancos. Lizzie Borden. Genene Jones. They look hard, pinched, swollen, unperfect. Ruth didn’t fit the model, the manner, the background. She was a minister’s daughter, a doctor’s wife. I knew it had to be self-defense.

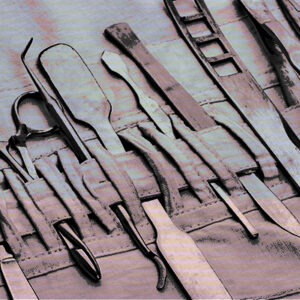

Within fifteen minutes of the files being delivered to my table in the Arizona State Archives, I knew that everything I had hoped about her innocence was wrong. Not only was I off the mark, I wasn’t even on the right map. The autopsy report of the victims revealed stippling on both of the victims’ temples, which indicates a muzzle-on-skin shot. It’s a powder burn. The entrance and exit wounds were almost parallel. Not the signs of a struggle, but the signs of an intentional shot, held with a steady and deliberate hand. Planned. Premediated. First-degree.

Over the next decade, I dug up everything I could about Ruth; letters, newspaper clippings, interviews, oral histories. I talked to other reporters who had studied the case, and one of them gave me the archival research of Sunny Worrel, a research librarian who spent her life devoted to uncovering every aspect; she was also the great-niece of Sammy Samuleson, the victim who had been dismembered. It was a treasure trove of cited, sourced information, some of which I had never seen.

Like any great story, the layers began to peel away to reveal a naïve woman who held a streak of wildness in her that she didn’t know how to harness. She wanted to love deeply, experience beauty, become a mother—all of which were beyond her grasp as she tried to reach for them over and over again, taking care and fixing the messes of her drug-addicted older husband. She was kind, I was relieved to discover. She did help people. She was a good friend. And then, in 1931, separated from her husband and stuck in Phoenix, she saw a last chance to touch everything that had escaped her in life. A furious romance that became her sole focus. A time of happiness, even solace, a slice of what she finally dreamed of—stability, a home, calm.

But then a threat emerged in the form of her dear friend, an interference that could destroy everything. The more I discovered about Ruth, the more I understood her, and how that awful night in October came to unfurl. And then I realized the most terrifying thing of all; I identified with her, a murderess who had taken the life of two people she loved most in the world. The acts on the October night were savage, evil and psychotic.

But I came to understand her, and I wrestle with that, because she took the lives of two vibrant young women unnecessarily. As I veered deeper and deeper in Ruth’s head, I sympathized with her, and to be honest, it was not hard, despite the fact that she was unequivocally a murderer. She took that step, made that decision. Alcohol, luminol and cocaine use did not help the situation, and Ruth found herself getting sucked in a whirlpool that was taking her down deeper every day.

In researching and writing The Murderess, I’ve learned the truth is not a two-sided coin. It’s multi-faceted, and the truth depends on who you talk to. Who you like the most. Who you find yourself trusting. There are so many theories about the murders even today that people discussing them get into arguments.

I knew that if I was going to write a solid book, I really had to ground myself in Ruth’s head and I had to stay there while writing the section that comes from her perspective. She lost focus on rationale as deep-rooted anxiety swept away common sense and reality.

It was a terrible, anxious place and I hated it. It was the greatest challenge of my writing career. It brought be back to times in my own life when I was in a bad place, and emotions and reactions I thought had long ago healed burst open again. Found myself in a frantic, uneasy, frenetic state relaying Ruth’s perspective. I didn’t sleep much, and when I did, had stress-induced nightmares that culminated into sitting with Sammy and Anne on a train.

I had to understand not only how Ruth committed murder, but also how I could do it, too.

I used to think that I could never commit such an act, but we are all fooling ourselves if we believe we have such a strong hold on circumstance and what constitutes a strong state of mind. People sometimes crack. Nice people. Kind people. The truth—no matter how many sided a coin it is—is that none of us can guarantee that given wrong place, wrong time, wrong set of circumstances—that we aren’t capable of horrible things. Truly horrible things well beyond the possibility of what we understand in ourselves.

There is still so much that I don’t know about the Ruth Judd case because everyone involved with it has now passed, and the truth has evaporated with them. Ruth’s death sentence was commuted to life in the state hospital, then known as the insane asylum. But the remainder of her life was fruitful; she cared for the children that were incarcerated with their mothers who were not able to care for them. She escaped the state hospital numerous times, the last for five years as she was a companion and caregiver to two separate elderly women before her recapture in 1969. In the early seventies, she was pardoned and lived a peaceful and uneventful life until her death at the age of 98, surrounded by people who loved her and respected her. I’ve talked to them. They adored her, calling her the most kind and generous woman they’d ever known.

But there are still two young women on a train in the 1930’s who look at me sternly and with awful disappointment. Sympathizing with their murderer does not sit well with them, and I understand that. Explaining to two victims that their killer had “some shit going on” can’t make anything better or change what happened. Their lives were over. They could have lived until 98, too, surrounded by friends and family who cared deeply for them.

Ruth took that from them, but I don’t think she really got away with it. She lived, but she was haunted for seventy more years about what had happened, disguising it as self-defense because she couldn’t believe she was capable of such horror, that events brought her right up to the edge that none of us think is possible or believable. It’s the stuff of nightmares, whether you’re a ghost sitting on a train, or a woman who cannot believe her own capacity.

I finished the book a year ago, and I was relieved to go back to my own life. The truth can be terrible, and it doesn’t always absolve or resolve. It just is, even if decades bury it and parts of it become unearthed, revealing lines that were crossed and mistakes made. I live day by day knowing now that good people sometimes do bad things, and although I’m not happy about that revelation, it is a hoovering reminder that horror and devastation is only as far away as circumstance allows.

And that goes for all of us.

***