The man holds up a thin, sharp instrument. “Do you know which story this is from?” he asks. I hesitate. I’m not even sure what it is, except that its end forms a wickedly curved needle.

I browse through my mental catalog of murder weapons and other questionable objects. I’m trying not to get distracted by the phrenological bust in the corner of the room, or the initials “VR” dotted onto one section of the wall in shapes that resemble bullet holes.

Denny Dobry smiles, takes pity. “It’s a nineteenth-century cataract knife.” Of course it is. Now I know what it’s from: the Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of the Silver Blaze.”

I’m in 221B Baker Street, the residence of Sherlock Holmes. But I’m not in London. I’m in Reading, Pennsylvania. Dobry, the man gleefully displaying that Victorian surgical instrument, is giving me and my family a tour of the room he built to mirror the home of the world’s greatest consulting detective. Outside are rows of houses with lawns so green they seem to glow, and actual white picket fences. Dobry’s own home matches this placid American dream—until you open the door to the basement.

I realize I’m making Dobry sound a bit fishy. Certainly, Sherlockians often strike others as odd. But while some Sherlockians are awkward, some are gregarious, and some are old fashioned, all Sherlockians are warm. When we first arrive, Denny and Joann Dobry greet us with two stuffed animal characters in Holmesian deerstalkers, Scooby Doo and Wishbone, one for each of my kids. Denny and Joann have been married over forty years. Retired now, they especially love talking about their grandchildren. But soon, a look of mischief crosses Dobry’s face. It’s time to see the flat.

Credit Denny Dobry

Credit Denny Dobry

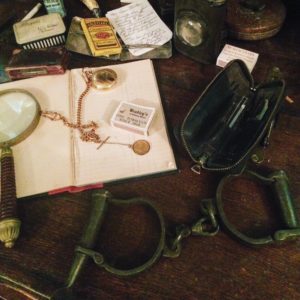

Dobry has recreated the 221B flat down to the last detail. (In correspondence I once called it an “apartment” and was told I had committed a faux pas: it was only ever a flat. The gentle admonition was accompanied, of course, with a quote from Doctor Watson.) There is the expected cozy armchair next to the fireplace, and garishly floral wallpaper. But there’s also a gasogene, a tantalus, and a dusty set of beakers for chemical experiments. Dobry proudly shows me late 19th-century tins of the four types of tobacco mentioned in the stories. And he is bursting with news of his latest find: an 1880s service revolver used by the British Infantry, which is the firearm Watson would have kept at his side during his time in the military.

Besides the actual artifacts from the era, the room is filled with objects that reference specific stories. A gold sovereign on a chain, like the one Holmes received from Irene Adler in “Scandal in Bohemia.” A plaster bust of Napoleon, reminiscent of the kind that gets repeatedly smashed to pieces in “The Six Napoleons.” As we walk through the flat, Dobry gleefully quizzes me: “Do you know which story this one’s from?” “Do you know what this is?” “How many types of tobacco ash does Holmes identify in his treatise?” (The answer: 140. Cf. “The Boscombe Valley Mystery.”)

This recreation may seem like an incredible feat. And yes, the hours of work, attention, and love that went into the flat are impressive. Dobry’s project is so well respected that his Baker Street Irregulars name, or investiture, is “A Single Large Airy Sitting-Room.” Yet in the Sherlockian community, there are at least three or four of these recreations in existence at any one time. A quick Google search will bring up painstaking diagrams of the flat, executed through multiple readings of the entire sixty works in the Holmes Canon. Objects referencing individual stories, like those in Dobry’s flat, are regularly created and auctioned off for charity at Sherlockian events. (One Sherlockian, a professional prop designer based in LA, makes items that are especially coveted.) Nor is it unusual for a Sherlockian to bring an 1895 Baedecker to a gathering as a conversation piece.

To outsiders, Sherlockians can seem at risk of veering dangerously close to a society of pedantic bores. But Sherlockians avoid that fate through an earnest and unabashed love for the subject. Your average Sherlockian manages to pull off sweet and swaggering simultaneously. In my experience, it’s hard to dislike a Sherlockian.

Once initiated in the ways of Sherlockians, I began to see their touch everywhere. Suddenly I noticed Wodehouse’s protagonist quoting Holmes, and scholars referencing the dog in the nighttime. My dentist talked about Jeremy Brett, one of the most beloved actors to play Holmes. My OB-GYN recommended (no kidding) a book called The Sherlockian. I heard of Sherlock everywhere.

This is how it goes for those of us who suffuse our lives in literature. The world is framed in a new way. It’s as if you’ve been given the ability to see another color you hadn’t known existed. Incorporated into your vision, you start to see it everywhere. And now you’re the one remarking on the deceptive nature of obvious facts, the cultivation of bees in retirement, or the virtues of Martin Freeman’s interpretation of Watson. This shared literary vocabulary provides a framework in which we can relate to others. The time-honored tradition of Sherlockians quizzing each other isn’t about condescension or pedantry. It’s a way to connect with people who share our same joys, no matter how strange.

At the end of the tour, my daughter grips her new, deerstalker-clad Scooby Doo and grins up at me. But Dobry isn’t quite finished yet. He takes us to one last room: his library. It’s cozy. And it’s curious: the shelves are filled only with books that have some connection to Arthur Conan Doyle or the Sherlock Holmes stories. Opposite us, in front of a wall lined with bookcases, is a slim side table with a single book on it, Arthur Conan Doyle’s Through the Magic Door. With some gentle prodding, Dobry gets my daughter to push on the bookcase next to this book. The bookcase swings open. We peer into the secret room behind it, the room whose entrance is marked by Arthur Conan Doyle’s book. I am enchanted. And so is my daughter.