It was the second week of September, but a cool, fitful rain spattered those who’d turned out for the opening of the annual San Gennaro Festival in New York, a stretch of days beloved of sausage-and-peppers food vendors and cannoli-eating contestants. It was the 93rd annual celebration of the feast, and there was no question that, despite the weather, the stately parade would make its way down Mulberry. A quartet of men pushed down the street the tablecloth-covered wheeled bureau which supported the statue of the martyred patron saint of Naples, followed by a marching band wearing green, white, and red, the colors of the Italian flag.

Over time, Little Italy has shrunk from 50 densely populated Lower Manhattan blocks to a three-block tourist-saturated radius around Mulberry Street. In a roughly parallel decline, the New York mafia, whose most feared members once plotted elaborate crimes in the neighborhood while meeting for dinner, has lost its grip. The heads of the famed five families died—some of them while in prison—and haven’t been replaced with vigor.

The San Gennaro Festival has figured in some of the most iconic films telling dramatic stories of the mob. Robert De Niro, playing a young Vito Corleone, shoots Don Fanucci, a “black hand” extortionist, during the festival in Godfather II, directed by Francis Ford Coppola in 1974. The festival features in Godfather III too, with another young Corleone, played by Andy Garcia, impersonating a NYPD copy on horseback and dispatching Joey Zaza, played by Joe Montegna. The festival serves as a setting for scenes in Mean Streets, directed by Martin Scorsese. As for television, the Italian American festival appears in everything from CSI: NY to a recent episode of the Showtime series Billions.

The same drizzly September evening as the festival’s opening, the New York mafia was actually the topic of a deeply informed discussion nearby. The talk was held at McNally Jackson on Prince Street, though the neighborhood that the independent bookstore lays claim to on its website is Nolita, not Little Italy. The occasion? A talk with two writers known for their mastery of nonfiction that chronicles the most infamous mobsters of our time: Anthony M. DeStefano, author of the newly published Gotti’s Boys: The Mafia Crew That Killed for John Gotti, and Nicholas Pileggi, author of the acclaimed books Wiseguy (1985) and Casino: Love and Honor in Las Vegas (1995).

DeStefano and Pileggi are good friends, both newspaper crime reporters who became mafia scribes. Yes, Gotti is dead, and Henry Hill and “Lefty” Rosenthal. And as mentioned before, the mafia is far from the criminal force it once was. But with Scorsese’s highly anticipated The Irishman being released in theaters and on Netflix next month, the mafia movie, television series, documentary and book are going strong. It’s become a genre of its own, a state of literary affairs that DeStefano and Pileggi discussed at McNally Jackson with insight, humor, and equanimity.

Their proximity to the onetime stomping ground of Cosa Nostra gangs was not lost on either author. “We sit in this locale a very short distance from the Ravenite at 247 Mulberry,” DeStefano told the packed audience. The infamous Ravenite Social Club housed the Anastasia and then the Gambino crime family meetings for more than 60 years, and it was the successful FBI bugging of the Ravenite that provided crucial evidence against Gotti. “Now I think at that address they sell shoes and leather goods,” DeStefano said with a smile.

“The Mafia has become almost like the Old West genre. It’s passed into American folklore, and people like these stories, whether they are true or fiction.”—Anthony DeStefanoIn an earlier interview, DeStefano, who writes for Newsday, said, “What’s happened is people still glamorize the Mafia, for reasons I’m not sure of. I was talking to my editor about it and he said the Mafia has become almost like the Old West genre. It’s passed into American folklore, and people like these stories, whether they are true or fiction. It doesn’t matter. These are now folkloric characters: John Gotti, Lucky Luciano, Frank Costello, Joe Bonanno. Just the lifestyle, the aura.”

For DeStefano, a longtime resident of New Jersey, it all began with his investigative story on mob involvement in the garment industry that ran in Women’s Wear Daily (WWD) in 1977. Working as part of a team, DeStefano said, “We spent six months reporting it. We looked through old newspaper files in the library, hit old court and business records, talked with detectives and prosecutors and garment industry people. It was tedious because not only were we cub reporters with few ties to police, but we didn’t have the advantage of computer data bases, Google, and the universe of federal court cases that all came later.”

Even based on such “primitive” reporting, the hard hitting WWD story made a splash. That’s when DeStefano met Pileggi, then an editor for New York magazine who was keen to commission a story about corruption in the garment industry. “There really wasn’t enough at that point to sustain a piece,” DeStefano explained. “Still, Nick and I stayed in touch, and over the years we swapped information and he encouraged my writing a book at some point, which I did. He also suggested my writing a book on the Lufthansa Heist.”

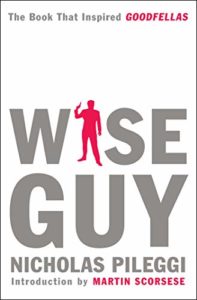

It was Pileggi’s bestseller Wiseguy that revealed to the reading public the planning and deadly aftermath of the Lufthansa Heist, the 1978 robbery of $5.9 million at John F. Kennedy Airport. But more than that, it told the story of gangster Henry Hill, who memorably said, “As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster.” Pileggi co-wrote the screenplay for the film adaptation of his book, Goodfellas, starring Ray Liotta, Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and Lorraine Bracco.

Pileggi was riveted by the lives of New York gangsters ever since he had an inkling who the men were. The son of first-generation Calabrese, Pileggi grew up in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. His father, who owned a shoe store, pointed the wiseguys out to him.

By the time he was 23 Pileggi worked as a reporter for the Associated Press. This was before Mario Puzo wrote The Godfather and before J. Edgar Hoover reluctantly told his G-men to trail the leaders of organized crime. Up until 1957, Hoover insisted the mafia was a myth and was obsessed with hunting down Communists. Meanwhile, carefully organized mafia families were taking control of not just gambling and prostitution but the construction, sanitation, and meat-packing businesses in New York and other major cities.

As his career continued, Pileggi covered the police beat, operating out of “the shack” for crime reporters in police headquarters. The old NYPD building was located at 240 Centre Street, between Broom and Grande streets, perhaps a five-minute walk from the Ravenite Club. Yet the mob carried on with impunity. Police seemed as unaware as the FBI of the extent of mob rule. “Crazy” Joe Gallo was shot to death by a rival at Umberto’s Clam House on Mulberry in 1977. Pileggi laughed over a practice of another mafia-friendly restaurant, Paolucci’s, at 149 Mulberry. In the 1960s it would close its doors for lunch every weekday to prevent any clueless cops from wandering in for a meal. “Mob guys” needed to relax over their pasta.

One memory that particularly lingered with Pileggi was catching glimpses of Neil Delacroce, underboss in the Gambino crime family and mentor to Gotti, on the street. “He had the coldest blue eyes I’d ever seen,” said the author. “So scary he didn’t need a gun.” A downpour soaked Mulberry Street one night, and Pileggi spotted Delacroce emerge from a tenement building with another man walking close behind him, anxiously holding an umbrella over the head of the gangster.

“I was just trying to figure them out,” said Pileggi of his fascination. “Maybe it was because I was trying to figure myself out.”

This eye for defining detail, as exhibited in Wiseguy, was part of what enthralled Martin Scorsese. “It was everything I’d hoped for and then some,” the director wrote in the Introduction to the 25th anniversary edition of the book.

As Pileggi entered the fray of film adaptations, DeStefano was covering major criminal trials for Newsday, including that of Bernard Goetz in 1987, the Happy Land Social Club in 1991, and former Bonanno crime boss Joseph Massino in 2004.

As a result of his coverage of Massino, DeStefano made the jump to books with King of the Godfathers: Joseph Massino and the Fall of the Bonanno Crime Family in 2008. He then wrote books on Charlie Carneglia, Frank Costello, and, yes, his own book on the infamous JFK robbery that figured in Wiseguy with The Big Heist: The Real Story of the Lufthansa Heist, the Mafia, and Murder. Pileggi praised it on the back cover as “terrific.”

In DeStefano’s latest engrossing book, Gotti’s Boys, the details of the mob leader’s leadership style are relayed as well as the significant roles played by those in his crew, such as Sammy “the Bull” Gravano, who was believed responsible for 18 murders yet ended up turning state’s evidence and testifying against Gotti at his trial.

During the Q&A portion of their appearance, the authors were asked if they ever felt themselves in physical danger while reporting their articles or books. The answer was no. Pileggi considers himself something of an anthropologist. “I covered them in the same way Margaret Mead wrote about the Samoa.”

While such writing may strike some readers as edged with both danger and glamour, mob books require plenty of old-fashioned diligence, sitting through long trials, working their sources, and shoe-leather reporting.

In a later interview, DeStefano said, “In covering the mob, about half the coverage is based on trials and court cases. There were more cases after 1977 and that helped flesh out the stories. As you do stories, you gain relationships with police and federal agents, who see that you are taking the work seriously. The books also help build contacts.”

McNally Jackson audience members, some of them highly knowledgeable on the mafia, wanted to pick the authors’ brains on the true story of certain mobsters or members of mob families around today. But the truth seemed to be that this was the end of an era. The grandchildren of John Gotti “belong on the show Jersey Shore,” Pileggi said. “They’re not a threat to society.”

DeStefano reminisced about the effect Gotti would have on the public when the “Teflon Don” appeared in public in his designer suits and the crowds that once gathered for Gotti’s annual Fourth of July party outside the Bergin Hunt and Fish Club in Ozone Park. Both men’s eyes lit up when they talked about the elaborate rituals and pageantry of a funeral of a major New York mobster.

“It’s an interesting world, and it was a wild time,” said DeStefano. “And I don’t think you’re ever going to see anything like that kind of mob funeral again.”

But what about Sammy “the Bull” Gravano? an audience member persisted. He was out of prison after being convicted on drug dealing. Wasn’t it possible he’d reappear in some way?

“He’s trying to get his life together,” DeStefano responded. “He wrote a book. Maybe he’ll do a podcast.”