I love fiction set in California. Even apart from the bizarre-world cultures of Hollywood and Silicon Valley, things are just different there. From the light that still feels straight out of Chinatown to the weirdly monotonous weather, nothing about the place seems to follow the expected rules. I especially love mysteries with a California setting, and though I’d never read Ross Macdonald before, The Zebra-Striped Hearse fit perfectly into my expectations of the genre. First published in 1962, it sends Macdonald’s detective Lew Archer on to a collision course with a charismatic artist/con man named Burke Damis. Damis is engaged to a young heiress named Harriet Blackwell, and Harriet’s father, a retired colonel, is far from happy about the match. The plot is terrific and impossible to protect, but that’s not all this novel has to offer.

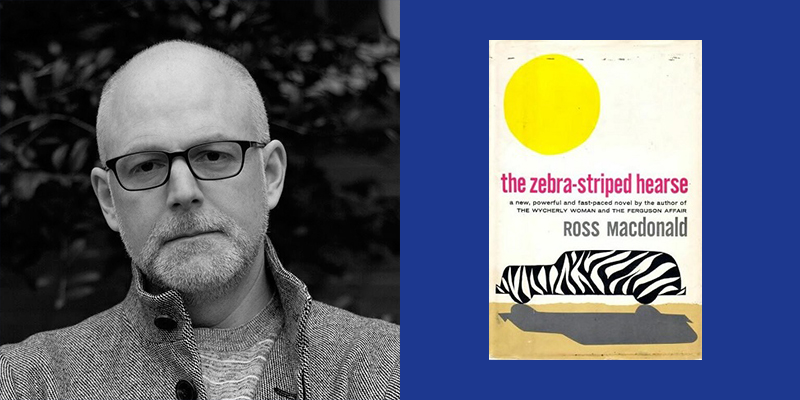

My guide to Macdonald’s work is John Copenhaver, author of Dodging and Burning, The Savage Kind, and Hall of Mirrors. He’s the winner of the Macavity Award for Best First Novel and a Lambda Literary Award, and his work has been nominated for the Anthony Award, the Strand Critics Award, and the Barry Award. Hall of Mirrors was also a New York Times Crime Novel of the Year. He lives in Richmond, Virginia.

Why did you choose The Zebra-Striped Hearse by Ross Macdonald?

I was on a Ross Macdonald kick a few years ago, and I think this one surprised me the most out of all the novels of his I read, because I found it really moving. Hardboiled fiction doesn’t usually move me. I can find those novels interesting, intriguing, and even riveting at times, but I’m not usually emotionally affected. Macdonald is really interested in human psychology, and his work stands apart from some other classic detective fiction in that way.

I also love the time period he’s writing about here, the early 1960’s. As a Gen Xer, I sometimes feel that

I’m a little bit between these warring generations, between the boomers and the millennials slash Gen Z. It’s like you’re on the tennis court watching the ball volley back and forth, and I think Macdonald’s protagonist, Lew Archer, feels stuck between generations in a similar sort of way. On the one hand, he’s got the parents’ generation represented by the Blackwells, and then he’s got the young people, like Harriet and Burke Damis, and he’s kind of shaking his head at both.

Were you familiar with Macdonald’s work before you started this reading kick, or were these novels new to you?

I wasn’t that familiar with him. I’d read Beast in View by his wife, Margaret Millar, and I don’t think I realized they’d been married at that time. Then I read Macdonald’s The Chill, and I thought it was fantastic, with a great twist. The books I enjoy the most are always more interested in the why than the who. You want to know who done it, but there’s a deeper level too. One of the things that attracts me to Macdonald is that he’s very interested in generational trauma and messed up families and how those factors might eventually lead to a crime, as opposed to a writer who is mostly interested in the unraveling of a plot. Everyone reads for different reasons, and I’m disappointed when there’s no attempt to explain the psychology, or when it’s something as simple as, “They did it for the money.” In real life, motives are more complex than that.

The one that bothers me is when it turns out that the perpetrator is a psychopath. It’s not satisfying to me to be told that someone just enjoys killing people.

Exactly. There are psychopaths in the world, but that doesn’t mean they’re always compelling on the page.

How would you compare Millar’s work to Macdonald’s?

I probably haven’t read enough of Millar to do a fair comparison, but I’d call Beast in View more of psychological suspense rather than a detective story, while Lew Archer is a private investigator. Not only is he literally a detective, but he functions that way in the story. The way he goes about investigating the crime is very methodical and professional, because that’s his job.

Have you ever thought about writing from the point of view of a professional detective?

It’s funny, but no, I have no interest in writing a detective character whatsoever. I think about this a lot because it makes me feel strangely deficient, but I’m just not interested in writing about professional detectives or cops. The reason that I’ve come to is that I’m interested in writing from the perspective of people on the margins. I tend to write about queer characters, and they’re usually operating on the fringe or in an amateur capacity. Not to say that there can’t be gay cops or private eyes, and there’s wonderful work out there from that perspective, but I write historical fiction, which makes it a bit trickier. There’s also the fact that when you’re writing about a private investigator or a cop, there’s a certain way that the story tends to move, and I don’t really want to tell that kind of story. I want to come to the puzzle through character, not through the circumstances of a case.

I thought that Macdonald’s prose was terrific, but some of the descriptions of the women in the novel are a little cringe. I think as readers, we all have different ways of reconciling our love for a writer with their frustrating blind spots when it comes to characterization–whether it’s of women, or queer characters, or people of color. How do you think about these moments in Macdonald’s work?

I think all these guys are products of their time, which in Macdonald’s case is the mid-twentieth century. I don’t find Macdonald nearly as offensive as I do Chandler, who is just baldly misogynistic. With Macdonald, his skill in characterization sometimes triumphs over that ingrained cultural lens, particularly, in this novel, in the case of Isobel Blackwell. There’s a conversation between Archer and Isobel near the end where he’s confronting her about her complicity, and he’ll say some pretty sexist things, but then there are also moments of real sympathy and understanding. Sometimes the hardboiled stuff falls away and you can see his compassion for the people he’s dealing with. I do think that anybody who is reading Macdonald should also be reading the women from this period—Dorothy B. Hughes, Margaret Millar, Vera Casper.

I’m glad that you made that point about Isobel. When she first goes to see Archer, it’s that classic trope of, “A broad walks in with legs up to here,” but she turns out not to be a femme fatale at all.

Yes, it’s interesting. He’s attracted to her, but he’s also suspicious of her, and he admires her, and it makes for complex interactions. There’s this great description toward the end of the book: “Isobel Blackwell looked at her hands. They were slender and well-kept, but the knuckles suggested a history of work. She massaged the knuckles as if she might be trying to erase the history.” That’s a great description, and it’s not sexualized. It almost seems like he identifies with her. We get more moments like that in Macdonald than we usually do with the portrayal of marginalized people in classic detective fiction.

There’s another moment where he’s talking about Harriet and he says, “I wasn’t looking at her as a woman. I was looking at her as a person in pain.”

That phrasing is interesting, isn’t it? It’s like Archer is aware of his knee-jerk misogyny, but he’s moving a step beyond it. He’s not fully successful, but he’s trying.

The title of this novel really intrigued me, partly because the plot has almost nothing to do with a zebra-striped hearse. Do you like it, and if so, why?

The title is great. For one thing, it’s such an interesting image. A zebra-striped hearse, what in the world? On a literal level, it’s a hearse that has been taken over by a bunch of teenage surfers who paint it to look like a zebra. They’re from that younger generation that Archer isn’t quite a part of—carefree, careless, silly, a little annoying. They keep appearing in the novel, and ultimately they do provide the clue that tells him who the killer. In that conversation, a kind of weight comes down on these young people as they realize that youth isn’t forever. They’ve been making fun of death, and now it’s here, right in front of them. They’re in much closer proximity to it than they think. It’s much more about thematic resonance than it is about plot.

And it’s not just the kids who are implicated in this carelessness. Archer is very critical of the parents’ generation too. They’re the ones who started all the problems in the first place.

The grownups aren’t really grownups after all.

That’s exactly right. Harriet makes some terrible decisions, but she’s put in a bad situation from the very beginning. Her father is very possessive and controlling, her mother dumped her to run off to Mexico, and her stepmother tells Archer that she didn’t love Harriet either. It’s brutal.

How would you define hardboiled fiction?

Again, I think it comes down to character and that character’s way of looking at the world. The classic hardboiled character is very emotionally cool, even armored. They look at the world with something between derision and skepticism, and it’s all in the service of protecting themselves emotionally. They’re very good at parsing everything around them, but they’ve isolated themselves from other people. That quality makes for a good detective, but it also makes them emotionally unavailable to the reader. Philip Marlowe is so much fun to read about, but I never feel like I know who he is. The vulnerability isn’t there.

Some people conflate noir and hardboiled, but I don’t think that’s right. Noir fiction is about fatalism and characters who can’t get off the path they’re on. The only question is to have dignity or not to have dignity in the end.

Apparently the Coen brothers wrote a script based on this novel that hasn’t been produced. Do you think it would make a good movie?

That would be awesome. They’re some of my favorite filmmakers, and they’d do it justice. I’ve often thought that Macdonald would be great for a limited series too. I thought it was a shame that the Perry Mason series got canceled, because it was doing really interesting things with the genre, and adapting Macdonald might present similar opportunities. As we’ve been saying, I think his work is so appealing because of its psychological complexity.

The Coen brothers would definitely put their own spin on it, though. It would be a little heightened and larger than life, a little exaggerated. At their best, the Coen brothers walk right up to the edge of silliness without stepping over it. At their worst, they step over it. Maybe they want to be silly, I don’t know.

Is there anything else you learned from this novel that you might apply to your own work?

There’s so much to learn from Macdonald when it comes to prose style. His poetic sensibility is there, but it’s not heavy-handed. He’s very economical, but never at the expense of description and characterization. He manages to create this rich sense of psychology without ever slowing the story down. These novels from the early 1960s on are particularly good in my opinion. I wish I could teach them, but I’m not sure that undergraduates would really get Macdonald. They don’t understand the tradition he’s working in, honestly, so I always start with Chandler instead.