While I’ve enjoyed every single one of the interviews I’ve done for this series, I do have a bucket list of the writers I hope I get to talk to at some point, and one of them is Attica Locke. Her Highway 59 series featuring Texas Ranger Darren Mathews is one of my favorite mystery series of all time, and her standalone novels are just as good. Like all the best crime writers, Locke manages to put together crackling, page-turning stories that are about more than just solving a puzzle. Now that she’s concluded Mathews’s story with Guide Me Home, I can’t wait to see what she does next.

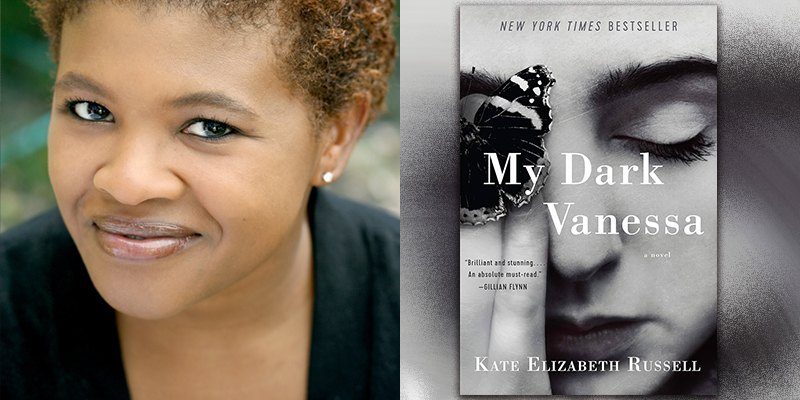

Excited as I was to speak with her, I was surprised when she told me that she wanted to talk about Kate Elizabeth Russell’s 2020 debut, My Dark Vanessa. I’d read the novel when it came out and loved it, but I’d never thought of it as a crime novel. The book tells Vanessa’s story in two timelines, going back and forth between her adult life and her teenage years, when she’s sexually abused by Jacob Strane, a teacher at her Maine boarding school. Part of what makes the novel both brilliant and difficult to read is that for much of the story, Vanessa doesn’t see the relationship as abusive. Even in the adult timeline, she insists that she and Strane are in love despite the nearly thirty-year age difference. In this interview, Locke and I talk about unexpected revelations in fiction, rereading Lolita in middle age, and why a novel about abuse is definitely a crime novel.

I read this novel when it first came out, and at that time I thought of it as very much tied to its cultural moment and the #MeToo movement in particular. Rereading it again now, though, I realized I’d forgotten how well-written and well-structured it is, and I feel like it’s a novel that people will still be reading twenty or thirty years from now. Do you agree?

Absolutely. I think about this book quite a bit. A sign of how much a book means to me is when I won’t lend it to anybody. I only lend books when I don’t care if I get them back or not. I loaned this one to my sister at one point, and when she didn’t read it right away, I was like, “Give it back.” I brought it with me for the interview today, because I wanted the physical object with me while we were talking about it. So yes, I definitely think it will stand the test of time.

The novel is in conversation with two earlier works by Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita (which is referenced frequently) and Pale Fire (which gives the novel its title). How do these earlier works speak to what Russell is doing here?

I will admit to you that I could not finish Lolita. I didn’t read it in high school or college, like a lot of people do. I read it as the mother of a teenage daughter, and I just I couldn’t get through it. I decided then that Nabokov wasn’t for me, and I haven’t read his other work. I did read Sarah Weinman’s book The Real Lolita, and I certainly know the discourse around the novel. I think of My Dark Vanessa as a reclamation of that narrative, because she puts the focus on the child rather than on the perpetrator. In a way, it makes me think of James, Percival Everett’s reframing of Huck Finn. This novel is a reframing and a reclaiming of the narrative of a teenage seductress. This is what the story of Lolita really the fuck is.

I read Lolita as a teenager, and I think back then I thought it was a love story. I’m sure if I reread it now that I have children, it would be a totally different experience.

Someone should write a book about a group of women who read Lolita in high school reading it again in their forties and fifties. That would be interesting.

I looked up some reviews and think pieces for research before this interview, and I was surprised by how many of them described My Dark Vanessa as “controversial.” Is that a word you’d use to describe this book?

I think it’s only controversial in the sense that a lot people don’t understand the psychology of this kind of abuse. Reviewers may have used that word because they wanted to protect themselves from the implication that young girls are asking for it. It’s a tricky situation, because for most of the novel, the narrator believes she’s consented to this relationship without understanding how she’s been played by this older man. It’s funny to me that people might be shocked by the idea of this happening, because it happens literally all the time. The word I would use to describe it is real—absolutely, uncomfortably real.

One of the things I love most is the way the writer establishes this double consciousness, where you can see the relationship the way Vanessa sees it as a teenager, but you can also see it from an adult perspective at the same time. From a craft perspective, do you have any thoughts on how she does that?

I didn’t read it that way. When I read the beginning of the book, I really thought, “Well, maybe this is the exception and they’re actually in love.” I feel like the narrator seduced me into believing that, even as a grown person who couldn’t finish Lolita.

I see what you mean. Even reading it for the second time, there was a point where Vanessa goes home with Strane for the first time, and a part of me was thinking, “Oh, this is going to be a sex scene.” Then, when you read it, it’s so awful. It’s one of the most horrifying scenes of sexual assault I’ve ever read, but she manages to trick the reader into thinking something romantic is going on, so then we’re forced to participate in the violation and horror along with the character.

Exactly. In those first chapters, I felt so close to the character that I believed her when she said, “We are special. Our thing is different.” And then at some point it flipped, just as it did for the narrator. When the narrator realized that she’d been in an exploitive and abusive relationship, I did too. It was a revelation for me as well, and I think that’s why it hit me so hard emotionally.

After accusations of plagiarism, Russell put out a statement on her website confirming that the novel had been inspired by her own experience. What would you say to readers who feel that they have the right to know whether a writer has been through the experiences they write about?

I think it’s very dangerous to make the assumption that the character and the writer are the same. My sister and I did an adaptation of her memoir, From Scratch, for Netflix, and we used some of the facts of our lives, but we bent them a lot. Since then, I’ve had people come up to me and say, “Oh, your mom ran off and abandoned you,” and I’m like, “No, I just made that up to add some drama.” I think it’s human nature to look for those connections, but you have to be very careful about taking these things literally. You can always Google an author and try to see what they have to say about their inspiration, but if you can’t find anything, you have to assume that they’re just very talented and invented something that moved you enough to convince you it was real. If the writing is so engaging and gripping that you think, “Well, you had to have lived this,” there’s a compliment in there.

I went to boarding school in the Midwest in the nineties, and just last month, alumni received an email about an investigation into past sexual misconduct by faculty. These cases have been in the news for years, but this novel doesn’t have a cheap ripped-from-the-headlines vibe. How does she avoid that?

I think it feels timeless because these kinds of incidents have been happening for a long time and continue to happen. Growing up is always a good subject. Reflecting on your past is something that people have always done and will always do. Reading a book like this, a reader recognizes and understands the truth of those experiences. Some of us may have experienced a kind of manipulation that has nothing to do with sex but has a lot to do with coercion. It could be a workplace incident or a dynamic within a family. Some version of this has probably happened to most people.

Is there anything else you learned from this novel that you might come back to in your own work?

I’d love to be able to flip the readers’ perceptions in the middle the way Russell does here. When the relationship was suddenly reframed and I understood the harm that Strane had done to her, I was so moved that I cried. You could do that even in a book that had nothing to do with sexuality or grooming. I love the idea that you could lead the reader down a path and then get them to look back at it with a whole new perspective in the last third. That’s kind of incredible, that tricking of the reader or shifting of perspective. It’s not quite the same, but it makes me think of Jessica Knoll’s Bright Young Women, which is a reframing of our tendency to obsess about serial killers and focus on them rather than their victims. It makes you ask, “Why are we giving this person so much power?,” and something similar is going on with the student-teacher dynamic here.

This conversation further reminds me of the big tent of crime fiction. I want to invite more people into that tent, and also invite us to understand that what we’re doing in this genre has much bigger implications than a lot of people realize. With any crime story, it’s not just about the facts—it’s about transgressions against other humans, and the psychological and political aspects of those transgressions. It’s so exciting to tell stories that invite us to think more deeply about these things. I think I’ve been on a mission, probably my entire career, to wave the flag for the power of this particular genre.