Riddle me this:

I am that which when completed never stops

Guards cities, and caves, confuses dimwitted cyclops.

Always exciting to turn over but hard to place right,

It can have four legs, then two legs, then three legs at night.

It turns ravens into writing desks, when neither’s like the other,

And reminds you that the old surgeon is really just his mother.

What am I?

(Yeah, it’s a riddle.) (In more ways than one.)

I’ve been thinking about the ontology of “the riddle” since seeing Matt Reeves’s new film The Batman, which offers a total retelling of the story of the Caped Crusader and his struggles to fight crime in Gotham City. This time, he faces off against the villain known as “The Riddler.” But this Riddler is not the one you might remember, not Frank Gorshin’s (or Jim Carrey’s) madly giggling, green-leotarded jester. He’s a Zodiac-killer-style psychopath in a baggy handmade suit on a murderous personal crusade to expose a massive conspiracy involving widespread corruption throughout all of Gotham. He wants attention and a playmate; he leaves behind codes and ciphers and puzzles, relaying clues in puns, jokes, mazes, little scavenger hunts, and, of course, riddles—all the sorts of flourishes you might expect from a guy whose real name is, historically, “E. Nigma.” Watching the film, I was fascinated at how deeply the story steeps in the Riddler’s methodology, genuinely reflecting on what riddles might mean for him, rather than simply taking his whole deal as a given.

More than simply existing as an embodiment of nefarious gamesmanship, the Riddler (played by Paul Dano) wants someone to understand him, and he wants that someone to be the Batman (Robert Pattinson), Gotham’s (fairly new, it seems) masked avenger. Batman is besmirched by most of the Gotham Police Department as a costume-wearing weirdo, with the exception of the morally-upright Lt. Jim Gordon (Jeffrey Wright, delightful), and he’s only starting to be taken seriously by the city’s criminal underworld, with the exception of mob kingpin Carmine Falcone (a superb John Turturro) and his right hand-man, “The Penguin” (Colin Farrell, underneath prosthetics so lavish that he looks like some random middle-aged guy). He is an outsider, a “freak,” much like the Riddler, and so with each of the Riddler’s sadistic murders, he does whatever he can to get the Batman on his trail. Solving someone’s riddle opens an understanding between you and them. The Riddler wants a partner. He wants a friend.

From the Batman’s perspective, the identity of the Riddler is simply a mystery, and for a while The Batman is a straight-up detective film—a dark buddy cop detective film, in which he and Gordon examine crime scenes, collect evidence, interrogate suspects, and convene at their rooftop bivouac to share their findings. Wright and Pattinson click like magnets, and some of the film’s best scenes feature their simple interactions: whispering plans to one another so other cops won’t hear, or finishing each other’s sentences while questioning the Penguin.

The film on the whole is a nod to the oeuvre of director David Fincher—not just for its thematic focus on murders conducted by a masked psychopath with symbols drawn on his chest, as in Zodiac, but for its emulating that film’s heavy emphasis on procedure and process, as well as that of another film with a ghastly breadcrumb trail: Se7en.

The Batman is a tactile, textured film about the human body as a material and a force; its Batman is, above all else, a man.Film noir is rainy and so is Gotham. But as in Se7en, there are sheets of rain, torrents of rain, suggesting an almost supernatural malaise; here, too, noir runs deeper, goes darker than mystery, with a killer determined to turn detectives into his own puppets rather than simply defeated pawns. The Batman, like these Fincher movies, is about doing detective work, which is fitting, since it features a villain who passionately demands work.

But the film is also about the work of being a superhero, which here isn’t easy or glamorous. When the Batman conducts surveillance (which he does often), he does so in a grimy bomber jacket and baseball cap, as if he’s an ordinary PI. Batman isn’t entirely fearless—he gasps when standing on high ledges, deploys a gadget incorrectly and injures himself, sometimes limps around. Often, when he’s fleeing an area, he must run through hallways of gangsters or cops—occasionally he’ll manage to vanish into thin air, but most of the time, he’s puffing his way down a flight of stairs at top speed. The Batman is a tactile, textured film about the human body as a material and a force; its Batman is, above all else, a man.

Batman films are no stranger to themes of distance, alienation, and solitude, but The Batman is invested in loneliness as a lens, as a key. Batman’s alter-ego Bruce Wayne is not the suave playboy, the disaffected dilettante of previous incarnations. Pattinson’s Bruce Wayne is a young man and an emotional teenager. And he’s very depressed. He wears baggy, unstylish t-shirts and petulantly dismisses the doting caretaking of his butler Alfred (Andy Serkis). The film’s frequent use of Nirvana’s “Something in the Way,” and its interweaving that melody through the instrumental score, ties these themes of angsty teen spirit to its grunge aesthetic.

Bruce is awkward and shy, antisocial and unsmiling. Pattinson curls his shoulders down whenever Bruce is out of the suit, a stark contrast to his ramrod posture when he wears it. But even when dressed as the Batman, the alter-ego that allows him to unleash his id, he also doesn’t know what to do around girls. When he meets and trails a young woman named Selina Kyle (Zoë Kravitz) whom he suspects might be involved in the Riddler case, he watches her through the window of her apartment from a rooftop across the way as she arrives home and changes her clothes. We see via subjective shots how he keeps his gaze on her, his face quivering and his breathing growing stilted, when she shimmies down to her underwear—he is a little immature, a little pervy.

The film uses this moment of kink to thread a larger point. Notably, this shot is nearly identical to the one that opens the film, in which someone (later revealed to be the Riddler) watches a family through the windows of their home before murdering one of them. The titillation the Batman experiences conducting surveillance in his mask is very similar to the Riddler’s—after he clubs his victim in the head with a giant metal tool, in the following scene, the Riddler mounts the body to duct-tape the man’s face and ends up gasping in what is likely a little throb of sexual pleasure.

The film is very careful to map the similarities between the Batman and the Riddler (including by featuring the article “the” in the Batman’s name), suggesting more than once that they might have become each other if their situations had been reversed. The Riddler even suggests to the Batman they are each their true selves in their suits, finally free to give into their darkest physical desires. They even have similar missions, ultimately: taking down Gotham’s most corrupt players.

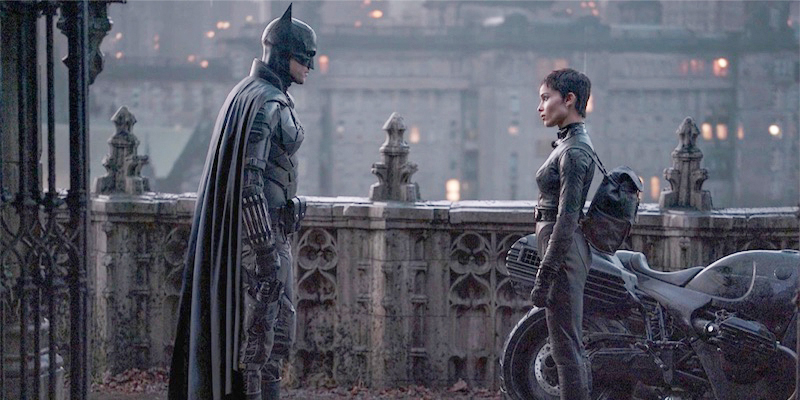

The Riddler longs to make a personal connection that will allow him to achieve his fantasies of dominance. Maybe so does the Batman, though he is still trying to figure out his desires: love or lust, defense or offense, retribution or forgiveness. Things grow complicated for him when he winds up working with Selina, as her alter-ego Catwoman, who has her own personal revenge quests, specifically on the men who have gotten away with hurting her and harming the women in her life. Pattinson and Kravitz have burning chemistry, in their romantic moments and their oppositional ones. But the characters are written to work towards understanding one another. If the Bat finds a partner, as the Riddler wants him to do, it is with the Cat, instead.

The film is very careful to map the similarities between the Batman and the Riddler… suggesting more than once that they might have become each other if their situations had been reversedBoth Bruce and Selina flirt with self-pity as they alternate selves, but the Riddler demonstrates it fully, recruiting goons in an online forum that feels just enough like the Proud Boys, just enough like incel culture: a carnival of white male loner entitlement and rage. The film is smart about how the white, wealthy, straight Bruce Wayne relates and doesn’t relate to this persona, and how the Batman guise might just be a more convenient, slightly-socially acceptable way for him to perform his own violent feelings. (Importantly, the Batman’s voiceover is revealed to actually be a log of his thoughts, a la Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle.) This thoughtfulness is what makes the film a productive, modern film; it settles in amid conversations about #MeToo, right-wing reactionary terrorism, and patriarchal accountability with its own inquiries, rather than simply rote performativity.

The Batman is three hours long, but it slinks along gracefully—in large part due to the mellifluous and multifarious score by Michael Giacchino. Its three leads have their own playful motifs that refer to specific genre hallmarks (such as the Riddler’s exorcism-evoking Ave-Maria-accented theme, creepily accompanied by a boychoir, or the longing strings that tail Catwoman). The music provides an extra level of genre-awareness that is helpful to a film whose ancestors have been both brooding neo-noir and ludicrous camp, and which is invested in honoring both identities.

Its length is one of its many strengths, to this end: it promises riddles and answers and a lot of procedure in between. It does not shortchange any of these components. It takes its time, works its way to illumination, allows characters to grow and adapt slowly—carefully braiding together the fiendishness with the fun of Gotham City. But most of all, it features the Batman working through the troubles that plague him personally as he fights crime—trying to alter his public and private approaches away from merely punching into the darkness.

It is a gritty, grave, glorious exploration of newly drawn characters, but also of the tropes that these characters are tied to. The Batman submerges you in shadow, letting you find your way through its labyrinthine construction—and like any good noir, or any good riddle, it is a pleasure to lose yourself in it.