There’s no stopping the true crime phenomenon sweeping over the culture these last few years, and why would you want to? Journalists, authors, and amateur sleuths are training a sharpened eye on pockets of society that have been too long ignored, helping to solve cold cases, and launching investigations into historical wrongs. The breadth of non-fiction books coming under the crime umbrella is truly astounding, as authors push past the boundaries of the old formats to find new ways of telling powerful and often intimate stories from life on the margins, where corruption, violence, and struggle are everyday affairs. As we’ve seen in the popular world of crime podcasts (and going back to the roots of literary crime), more and more writers are willing to inject themselves into the story and to fill in the holes where police and government authorities are unable or unwilling to act. We’re also seeing more interrogation of classic texts, from the literary world as well as the vast modern landscape of television, as writers reckon with the crime wave that’s taking over the culture. What these books all have in common is the investigative impulse—a need to go beyond the accepted wisdom and to leave no stone unturned in pursuit of answers and obsessions. We’re living in quite an era for true crime, and there’s no end in sight. Here are our picks for the best non-fiction crime books of 2018.

Michelle McNamara, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark (Harper)

The scope and intensity of McNamara’s investigation into the man she dubbed the “Golden State Killer” would be reason enough to read this book. The fact that she also ruminates on her own lifelong interest in crime and the personal stories that set her on a life’s path makes this an even richer read. It’s heartbreaking to know she didn’t live long enough to bring her subject to justice, but gratifying to know that her efforts helped keep the search alive and that now, with a suspect finally in custody, survivors may find some sense of peace.

Sarah Weinman, The Real Lolita (Ecco)

The Real Lolita is marked by the same quality research and gorgeous prose that distinguishes all of Weinman’s writing and is sure to be a new classic of true crime. Weinman delves into the story of Sally Horner, an eleven year-old girl who was kidnapped in 1948, and whose story helped inspire Vladimir Nabokov to write his classic, Lolita. Horner, long pushed aside in the historical conversation, is front-and-center in this story, which is also about the distortion and manipulations of cultural memory and artistic achievement. This is that rare blend of historical re-appraisal, rigorous archival work, insightful analysis, and endlessly engaging writing.

Gilbert King, Beneath a Ruthless Sun (Riverhead)

Gilbert King’s latest investigation looks at the many layers of corruption and mystery swirling around a late 1950s case stemming from the rape of a Florida citrus baron’s wife. A backwards local sheriff railroads a series of suspects, while a crusading journalist pushes ahead in the face of tremendous resistance and secrecy. King’s book unfolds a conspiracy implicating institutional racism, mental healthcare, treatment of the mentally impaired, and the fabric of Southern town life in the buildup to a truly tumultuous era.

Paul French, City of Devils (Picador)

Few epochs stir up quite so much intrigue, mystery, and glamor as Shanghai in the 1930s: a divided city, a bustling port, a crossroads for the world, and a kind of frontier outpost where the citizens largely made up their own laws. In Paul French’s City of Devils, that epoch is brought to life in brilliant fashion as French conjures up the world of “Lucky” Jack Riley and “Dapper” Joe Farren, two expats who lorded over the Shanghai nightclub circuit and soon got involved with all manner of illegal activity. French, the author of Midnight in Peking and a regular contributor here at CrimeReads, has a rich sense of place and an assured, engaging style that adds impressive layers of complexity and humanity to historical figures all but forgotten to time. City of Devils represents the very best of historical true crime: learned, gritty, and raucous.

Jonathan Abrams, All the Pieces Matter: The Inside Story of The Wire (Crown Archetype)

The oral history is tricky business but Jonathan Abrams is one of the finest practitioners at work today, and in his latest book he takes on a subject more than worthy of this multi-perspective, complex, and highly nuanced approach, The Wire, the groundbreaking crime show that premiered on HBO almost seventeen years ago and continues to captivate. Abrams managed to get access to all the show’s creators and actors and through their memories presents a portrait of an important cultural artifact, one that still shapes how we view the modern urban experience, the drug war, community policing, surveillance, and a host of other social policies.

Fox Butterfield, In My Father’s House (Knopf)

In My Father’s House is a family portrait and a study in big ideas that begins with a provocative point: that a large percentage of America’s crime can be traced back to a relatively small number of families. Butterfield, a Pulitzer Prize-winner and a New York Times stalwart, dives into this insight with a close study of one Oregon family that has sent generations of its members to prison. This is the book that’s going to be posing difficult questions about mass incarceration, cultural marginality, and persistent communities of lawlessness.

Sarah Krasnostein, The Trauma Cleaner (St. Martin’s)

The elevator pitch for the trauma cleaner would go something like this: Australian journalist follows woman who owns a cleaning service that specializes in scouring crime scenes, the homes of suicides, and other difficult jobs (quite a few of her clients are hoarders or suffer from mental illness and have to be handled very sensitively). But there’s more: Sandra Pankhurst, the extremely hands-on owner of the service, is a transsexual who left her former wife and sons when she decided to live as a woman. Pankhurst is an engaging, sympathetic, and fascinating figure, and Krasnostein does an excellent job of balancing Pankhurst’s personal story with those of her clients. This is one of the most insightful, surprising crime books you’ll read this year.

Alex Perry, The Good Mothers (William Morrow)

Alex Perry takes us in to the patriarchal, ultra-violent world of the ‘Ndràngheta, Calabria’s powerful, drug-dealing mafia, and the stories of the women who have defied its iron grip on the region, risking (and often losing) their own lives after turning state’s witness, despite being placed in witness protection programs. Perry also profiles the tough-as-nails prosecutor who’s worked to bring the Calabrian Mafia to heel ever since the assassination of her predecessors. With elegant forays into the harsh landscape of Calabria, and digressions on Godfather-inspired tourism, The Good Mothers is more than a mafia story, critiquing the allure of exploitative tales of power and destruction, and using empathy as a defense against any temptation towards the lurid.

Ron Stallworth, The Black Klansman (Flatiron)

Ron Stallworth had recently joined the Colorado Police Department as the department’s first African-American policeman when he embarked on a daring mission: infiltrate the KKK. His new memoir, The Black Klansman, details how Stallworth spent years running circles around the Klan and getting away with increasingly risky undercover moves, escalating from phone calls with the Klan, to a series of meetings organized between the Klan and Stallworth’s white undercover body double. Spike Lee’s film adaptation of this darkly comedic narrative was greeted with critical acclaim, and makes an excellent companion to its source material.

Javier Cercas, The Impostor: A True Story (Knopf)

Javier Cercas, wildly creative author of many works of fiction and non-fiction, investigates the life and lies of Enric Marco, who spent decades claiming to have been one of the few thousands of Spanish Republicans imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps before being revealed as an imposter by several historians working on the history of Spain in WWII. Cercas worries about giving so much attention to a man who clearly craved it, but ultimately this meditation on truth and lies, fiction and non-fiction, Spanish history, and Spanish revisionism, is about far more than one man’s falsehoods.

Margalit Fox, Conan Doyle for the Defense (Random House)

Arthur Conan Doyle has long be renowned for his creation of the iconic Sherlock Holmes, and Conan Doyle’s own life is well-trodden territory in the land of biographies—there are even microbiographies such as Through a Glass Darkly, a heartbreaking history of Conan Doyle’s obsession with seances after his son’s death in WWI (and not the only work to explore Conan Doyle’s connection with Houdini and seance culture). Yet until now, Conan Doyle’s part in defending a Jewish immigrant wrongfully accused of murder in 1908 Glasgow had not been told. Margalit Fox’s Conan Doyle for the Defense is both a rare tale of logic in the face of prejudice and indifference, and the perfect narrative for our time.

Jonathan Green, Sex Money Murder (Norton)

Green’s account of a notorious Bronx gang headquartered in the Soundview housing projects is not for the squeamish. The gang takes over the crack trade in the projects and branches out to deal in other East Coast cities, places like Buffalo, New York and Springfield, Massachusetts, where the drug is much more valuable due to its scarcity. They also kill with impunity: to be an enemy of the gang is to basically write your death warrant. Expertly reported and written in a crisp, no nonsense style, Sex Money Murder is a glimpse into a violent criminal lifestyle rarely documented.

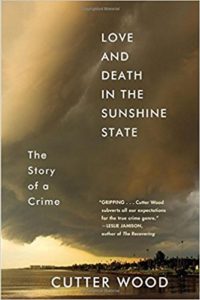

Cutter Wood, Love and Death in the Sunshine State (Algonquin)

When a MFA student staying in a sleazy Florida motel starts researching an arson and a disappearance, true crime poetry is born. Cutter Wood, a writing student at Iowa, explores the disappearance and murder of a local woman in a small Florida town, and in doing so, finds “the symptoms of a universal decay, among which the disappearance of a woman was only the most striking example.”

Piper Weiss, You All Grow Up and Leave Me (William Morrow)

Weiss’s hybrid book blends a memoir of a privileged childhood on Manhattan’s upper east side with a true crime story about her tennis teacher, Gary Wilensky, who became fixated on one of his students and killed himself after a failed attempt to kidnap the object of his desire. In researching the book and telling both her own story and Wilensky’s, Weiss tries to make sense of Wilensky’s behavior—the title refers to something he once told her about his charges, that teenage girls inevitably become grown women and put aside their teenage fantasies and desires. As the teenaged Weiss exults in being one of “Gary’s Girls,” looking forward to her lessons and hanging out with Wilensky, who treated his students like adults, the grown woman Weiss obsesses about Wilensky’s habits and his eventual crime, when he tried to bring a girl to an upstate cabin dubbed a “Cabin of Horrors” by the media. You All Grow Up and Leave Me is thoughtful and strikes the right balance between recollections of childhood and the digging the adult Weiss has done in order to make sense of Wilensky’s actions.

Stephen L. Carter, Invisible (Henry Holt)

Stephen L. Carter, a Yale Law professor and one of the country’s first rate legal minds, is well known to high-brow mystery and thriller fans as the author of The Emperor of Ocean Park and Back Channel. He’s also, as it turns out, the grandson of a trailblazing lawyer named Eunice Hunton Carter, who was part of an elite prosecutorial team (the team’s only non white male member) taking on the mob in 1940’s New York City, and was the mind behind the plan that ultimately took down Lucky Luciano. In Invisible, Carter tells his grandmother’s powerful story: a story about crime, justice, race in America, the Red Scare, gender inequality, and family strife.