The CrimeReads editors make their selections for the best debut novels of the year.

*

Iris Mwanza, Lions’ Den

(Graydon House)

In The Lion’s Den, set in Zambia and based a famous real-life case, a queer dancer disappears while detained by police after a raid on an underground gay club. Despite facing immense social pressure to drop the case, an intrepid and heroic lawyer is determined to find, and defend, her client. The Lion’s Den makes a powerful statement: no matter what you can actually achieve while fighting injustice, sometimes trying to do the right thing in the face of adversity is itself a form of victory. Beautifully written, well plotted, and with fully fleshed out characterizations, The Lion’s Den is not to be missed. –MO

Amy Tintera, Listen for the Lie

(Celadon)

In Tintera’s debut, a Texas town finds itself the subject of a hit true crime podcast, and the woman at the center of the investigation, once implicated in the killing of her best friend, returns to her hometown to reckon with the mystery of what really happened that night. Tintera creates a perfect small town pressure cooker, where everybody has a theory, and everybody is guarding a secret. Appearances are ripped apart, and the truth, or some version of it, slowly emerges, all handled with perfect pacing by Tintera, whose first novel indicates a writer very much on the rise in the world of suspense. –DM

Joshua Perry, Seraphim

(Melville House)

In this bleak and beautiful tale, full of good intentions and systemic injustice, a public defender will do anything to free his young client. Perry is himself a defense attorney who worked with young people in the book’s setting of New Orleans, and authenticity shines through in every detail, conversation, and world-weary opinion. Here’s hoping Seraphim is the start to a long career and a revitalized legal genre.–MO

Anna Rasche, The Stone Witch of Florence

(Park Row)

The gemologist and historian Anna Rasche made a stirring debut this year with the elegant mystery, The Stone Witch of Florence. The story follows a so-called “stone witch,” a 14th century woman living in exile because of accusations of witchcraft, but wishing to bring her skills—healing through the power of gems—back to her home city during its battle with the plague. When she’s welcomed back by elders, she’s soon set on another journey—to find a thief targeting local relics—and her efforts are revealed to be part of a broader and more insidious conspiracy. Rasche fills the story with evocative detail and fascinating stories from the era, but it’s the magic of the stones that really brings this novel to life and delivers to readers a remarkable mystery. –DM

Jacquie Pham, Those Opulent Days

(Atlantic Monthly Press)

This book will make you feel things—mostly, a simmering anger against capitalism and colonial exploitation, but also some very sad thoughts about thwarted love and and the oppressive power of self-loathing. Those Opulent Days, set in 1920s Vietnam under the yoke of French colonialism, follows four young men faced with increasingly impossible decisions as revolution grows nigh and a terrible death becomes the catalyst for many more misfortunes. Pham’s voice is self-assured and brutally honest, as the subject matter deserves (and demands). –MO

Lily Meyer, Short War

(Strange Object)

Meyer’s debut is a sweeping, cross-generational love story that also manages to be an incisive study of the US’s disastrous influence in the sphere of South American politics. The lives of Americans, Chileans, and Argentinians is observed in close, evocative detail. With a shifting perspective that subtly alters the story, Short War gathers momentum and delivers a series of compelling portraits of lives moving between the two hemispheres. It’s a literary detective novel, a political novel, and an epic: a wildly ambitious project, and Meyer delivers in admirable le fashion. –DM

Kobby Ben Ben, No One Dies Yet

(Europa)

In 2019, Ghana declared a “Year of Return” and welcomed tourists from across the diaspora to visit the country. That is the backdrop for Kobby Ben Ben’s psychological thriller featuring four American tourists and their competing guides—one religious and humorless, hired to take the Americans around the official sites, and the other queer and cynical, brought in through a dating app to give the tourists a taste of Ghana’s gay underground. This may be one of my favorite novels ever. It’s so funny. It’s like Patricia Highsmith traded her self-loathing for a decent sense of humor. –MO

Vanessa Chan, The Storm We Made

(S&S/Marysue Ricci Books)

In Chan’s powerful debut novel, it’s 1945 in Malaysia, and a mother finds herself forced into an impossible situation. She has a son missing, a daughter in hiding, and another child deeply embittered by her current situation; and the mother knows that much of their current predicament can be traced back to her decision, a decade earlier, to begin spying for a very persuasive general. Chan deftly shifts perspective to tell an ambitious story about the region and one family caught up in the shifting historical moment. The Storm We Made is an audacious debut and a clear standout among the year’s espionage novels. –DM

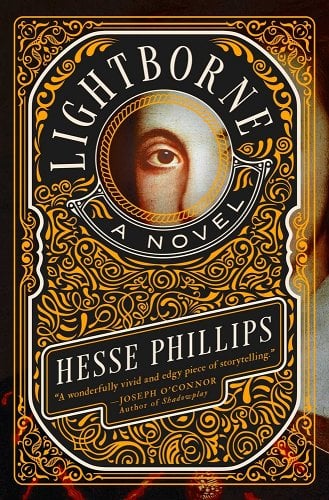

Hesse Phillips, Lightborne

(Pegasus)

A queer historical reimagining of the last days of Kit Marlowe! With spies and romance and an absolutely devastating denouement, Lightborne is as bloody and beautiful as the great Marlowe’s plays. You don’t need a dissertation on Elizabethan drama to understand this one, but the author’s academic research evolved in parallel with crafting the narrative, and the ease with which they incorporate telling historical details is an incredibly rewarding experience. Lightborne is so much more than its details, no matter how outrageously entertaining, for the soul of this work comes from its clear-eyed portrait of humanity: the best, the worst, and the somewhere-in-between. –MO

Emily Dunlay, Teddy

(Harper)

In this madcap tale of espionage and adventure, a Dallas debutante marries a foreign service worker and heads to mid-1960s Italy, determined to put her wild days behind her and finally Behave. Events conspire to foil her goals of proper deportment, and soon enough, she’s involved in a blackmail scheme, embassy hijinks, and the most daunting task of all: finding a couture dress that can fit her without needing to be tailored. Teddy is not just a fabulous historical novel—it’s a manifesto against the patriarchy, and a liberating experience of watching a woman free herself. –MO