I’ve always enjoyed books set in or about the theatre, particularly for adults. My novel, The Whalebone Theatre, features several: one, created by children from the ribcage of a whale on the English coast; one in London in 1928, where the legendary Ballet Russes perform, and one in Nazi-occupied Paris during WWII. My research into the theatre in London and Paris drew primarily on historical records and social histories, but for the theatre that serves as the title of the book, I drew on my own experiences as a child who liked putting on shows with her friends and a young student who briefly trod the boards at university. Here is a list of the best books about theatre.

Ballet Shoes, by Noel Streatfeild

The urtext for me, as far as books about theatre are concerned. Streatfeild’s tale of three orphan girls who go to stage school, with a household of interesting lodgers and warm-hearted guardians cheering them on, is a children’s classic for good reason. But Streatfeild doesn’t shy away from depicting the bleakness of children from cash-strapped families having to audition to help pay the bills. Nor does she allow her characters to become starry-eyed. The eldest Pauline becomes unbearable when she gets a main part – and is quickly demoted (‘nobody is irreplaceable’, the director tells her). But despite its harsh lessons, the stage offers the determined sisters their best chance to make both their fortune and their name.

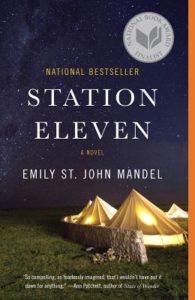

Station Eleven, by Emily St John Mandel

Mandel’s justly praised novel is one of my favourites of recent years. Set before and after a devastating pandemic, it begins with a production of King Lear. The book asks: what happens when everything we know and rely on is taken away? Who are we when our needs are reduced to only survival? Do we turn to violence or religion? Community or isolation? The different characters in this book offer different answers, but the most compelling are those who form part of The Traveling Symphony – a tiny theatre troupe travelling in horse-drawn vehicles (there’s no petrol on the far side of societal collapse) visiting isolated pockets of survivors and performing Shakespeare (“what was best about the world”).

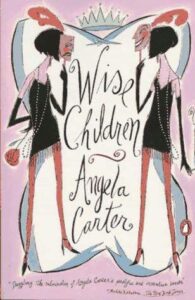

Wise Children, by Angela Carter

Shakespeare is also threaded through Angela Carter’s warm and witty Wise Children. It opens with a list of ‘dramatis personae’; is set in five chapters or five theatrical acts; stars several sets of twins, and is a high-kicking celebration of theatre in all its varieties. The main characters, Dora and Nora Chance (‘two batty old tarts’), are illegitimate daughters of a distinguished Shakespearean actor, but they tread the boards at the ‘fag end of vaudeville’. As in Ballet Shoes, the theatre is a place where women and girls can make a living, of sorts, though Dora, our narrator in this exuberantly joyous novel, ‘refuses, point blank, to play in tragedy’.

Our Country’s Good, by Timberlake Wertenbaker

Based on a novel by Thomas Keneally, Wertenbaker’s award-winning drama tells the story of a British officer trying to put on a play in an Australian penal colony in the 1780s. The officer’s intentions are pompously idealistic, a worthy top-down approach to distributing culture, but the play has an unexpected effect on both the ‘thieves, perjurers, forgerers, murderers, liars, escapers, rapists, whores’ and their ‘ghouly gaolers’. At university, I played the part of Dabby Bryant – a scrappy convict unconvinced by artistic nonsense – but Wertenbaker’s play convinced me of how the theatre can transform people. More than any other text, this one taught me about the power of performance. “A play is a world in itself, a tiny colony”

Tipping the Velvet, by Sarah Waters

Theatre’s transformative opportunities are also explored by Sarah Waters in this ground-breaking lesbian romance. It follows the picaresque career of Nan King, Whitstable oyster girl turned stage star turned rent boy, and in doing so, prises open the historical novel to reveal the more interesting, radical stories hidden inside. Like the Chance sisters, Nan inhabits the seedier end of theatre – the dingy Victorian music halls, where young hopefuls with ‘greasepaint on their cuffs and crumbs of spitblack in the corners of their eyes’ try to win over drunken audiences – but it’s in this half-lit, transitory space, where costumes can be put on and taken off, that new selves can be discovered.

Theatre of War, by Bryan Doerries

I heard Doerries talking about this book on a podcast during a particularly bleak walk in lockdown and was moved by how he described the ability of Greek drama to speak to us across the centuries. His memoir tells the story of how he began using classical drama as a tool for public engagement and as a way of helping people heal from trauma. At that time, I had been researching theatre in Occupied Paris, and was struck by the fact that both Nazi troops and French citizens had flocked to see a production of Antigone by French playwright Jean Anouilh. The Greek tragedy seemed to speak directly to their very disparate experiences in that wartime city. They sensed what Doerries explores so movingly: that theatre can be a light in the darkness.

***

–Featured image: Sir John Gilbert’s 1849 painting: The Plays of William Shakespeare at 420 scenes and characters from several of William Shakespeare’s plays.