As America becomes an increasingly untenable place, reading widely from a variety of cultures and languages feels ever more essential, if only as an antidote to growing xenophobia. This year brought innumerable and wondrous translations to our cursed shores, and here assembled are some of the best. Like all good crime fiction, they are meant to be read as a warning—there but for the grace of God are we when it comes to bad behavior, and we must read to explicate our own sins, not to justify our indulgences. Also in the mix are those works about giving in to our own impulses: to love, to protect, and to rebel.

Genre-wise, the list is a mixture of noir, psychologicals, horror, and thrillers; all are good, and all are equally deserving of your time and ready to provide you with the perfect distraction. One further note: I included several reissues on the list, partially because the conversation between past and present is easily seen in which books get brought back into print when. International fiction matters. Translation matters. Reading matters. So thank you for reading this, and thank you for believing in the power of literature, at a time when it feels difficult to believe in much at all.

Irene Graziosi, The Other Profile

Translated by Lucy Rand

(Europa)

Who needs a personality, when you can hire someone to craft one for you? In this highly relevant psychological thriller, an Italian writer is hired to shape the social media taglines of a mysterious and beautiful teenage influencer in this internet-era-Single White Female. With the rapid advent of AI, we’re all in danger of having our work stolen and our identities replaced, and The Other Profile has turned out to be more prophecy than fiction. I’ll be spinning this thought soon into a piece on doppelgangers, changelings, mirrors, and the slippery nature of modern identity and creative ownership—all essential themes to understanding both this text and the world that made it.

Akira Otani, The Night of Baba Yaga

Translated by Sam Bett

(Soho)

This queer thriller stole my heart! When a mixed-race fighter from the northern islands impresses a brutal Yakuza boss, he hires her to protect his sheltered daughter. The new bodyguard soon realizes that to truly protect her enigmatic charge, she must free the young woman from the tyranny of her father. The Night of Baba Yaga balances impeccably choreographed action sequences with rare but powerful moments of tenderness. The ending left me stunned—and completely satisfied.

Aleksandr Skorobogatov, Russian Gothic

Translated by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse

(Rare Bird Books)

Aleksandr Skorobogatov’s haunting masterpiece of jealously and rage first came out in 1991, but it’s taken three decades to make its way over to English-language audiences. In Russian Gothic, a veteran with severe PTSD is convinced his wife having an affair, a conjecture put forth by the mysterious Sergeant Bertrand, who is either a conniving mastermind or a hallucination conjured up to confirm the narrator’s suspicions. Reality is doubly questioned via the veteran’s wife, who splits her time between pretending to be in love on stage and pretending to be okay in the presence of her increasingly violent husband. This book might as well be titled “Russian Grand Guignol,” for the plot is not for the faint-hearted.

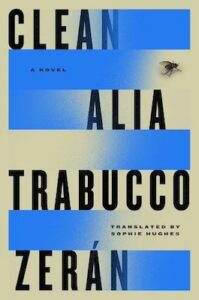

Alia Trabucco Zerán, Clean

translated by Sophie Hughes

(Riverhead)

A housemaid in prison narrates her tale of woe as a confession in this visceral exploration of class, privilege, and humanity. It is clear from the beginning that something terrible has happened to her employers’ young daughter, but we must wait for a complex story to unravel before learning exactly the nature of the tragedy. Heartbreaking, furious, and a modern masterpiece!

Layla Martinez, Woodworm

Translated by Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott

(Two Lines Press)

This book is so creepy!!! In a visceral exploration of the absurdities of male control, a woman and her grandmother are trapped in a house of horrors, built by a husband who cursed his female relatives to be bound to the abode, only to be trapped there himself, along with numerous other spirits. It’s all pretty bearable if you don’t let the ghosts think you’re getting too vulnerable—just don’t look under the bed, and if something grabs your ankle, squash it ever so firmly. Grotesque brilliance, all the way through.

Asako Yuzuki, Butter

Translated by Polly Barton

(Ecco)

In this sumptuous tale, a gourmand hedonist and suspected serial killer becomes the object of a journalist’s fixation, and perhaps, an inspiration. The killer is known as a woman whose unending appetites for rich cuisine have led to the deaths of multiple paramours. Did she murder them, or could they simply not keep up? Why is it always a woman’s job to enforce healthy limits, to care for men? Why is it not the man’s job to care for himself? And what can we learn from these simple, rebellious acts of indulgence? This book is best paired with a multi-course meal among friends.

Tanguy Viel, The Girl You Call

Translated by William Rodarmor

(Other Press)

Viel’s latest demonstrates an acute sense of the imbalance of power and the gradations of control accompanying gendered violence and sexual exploitation. In The Girl You Call, an aging boxer finds his comeback disrupted by revelations about his daughter, coerced into an arrangement by his boss, the mayor. Tanguy Viel writes some of the sharpest, most cynical, and most insightful prose around, and his new novel is particularly dexterous and disturbing.

Seicho Matsumoto, Point Zero

Translated by Louise Heal Kawai

(Bitter Lemon)

In this welcome reissue of a lost classic from 1959, a young woman is wed to a businessman via arranged marriage, only to have him disappear soon after their honeymoon. She barely knows the man, much less what could have happened to him, but still finds herself in dogged pursuit of the unvarnished truth. The immediate post-war era in Japan looms large as the backdrop to understanding the context of her husband’s disappearance, and her own reasons for searching.

Nawal El Saadawi, Woman At Point Zero

(Bloomsbury Academic)

Woman at Point Zero is one of five classic works by the great Egyptian feminist writer Nawal El Saadawi to be reissued by Bloomsbury this year, and an essential work of social criticism. Structured as a confession from prison, this sharp sliver of a story takes into the life of Firdaus, a sex worker soon to be executed for murder. Her lack of shame for her violent act first shocks, then inspires, for a novel that feels as revolutionary now as when it was first published. Also because this came out in the 70s, over a decade after the previous item on this list, I really need to know if the title is an homage to Matsumoto’s book. They certainly would read well in juxtaposition!!

Johan Harstad, The Red Handler

Translated by David Smith

(Open Letter)

This book is so weird (in the best possible way). The Red Handler is a riotous metafictional parody of the genre travails of literary authors trying to make a buck. Harstad’s disillusioned detective novelist once published a 2,000 page tome reviewed by all and read by none. After his first, spectacular failure, he turns to the adventures of a fictional detective to earn some quick cash, thus setting the groundwork for this book’s central conceit: we are reading the complete, annotated works of an egotistical litfic bro turned terribly mediocre crime writer whose detective does nothing much at all. You will laugh. You will cry. You will feel like smoking a cigarette. I can’t recommend this bizarre and hilarious work enough.