In July 1902, a fully rigged English merchant ship, the Leicester Castle, arrived from Hong Kong at San Francisco, its iron hull heavy with wheat. After docking, its Scottish Captain Robert D. Peattie expected to lose much of his crew of 26 men as a matter of course; sailors typically scattered for the excitements of San Francisco once they were paid off, picking up a new ship when they again felt light in the pocket.

Capt. Peattie needed to replace more than half his men before heading out again for the long route to Queensland, northeastern Australia. He paid a shipping master named John Savory, who rounded up fourteen candidates living at sailor boarding houses around the city. The ship’s registry recorded their range of origins: Ireland, Sweden, Finland, “Leghorn,” Germany, “Chili,” Isle of Man, “Liverpool,” as well as from the ‘U.S.A.’ When several Americans and a German named Christian Wolz (who signed on as ‘Wolf’) were brought on board, one of them, W.A. Hobbs, was told to surrender his Colt revolver to the Captain. Hobbs made no promises against sneaking ammunition aboard.

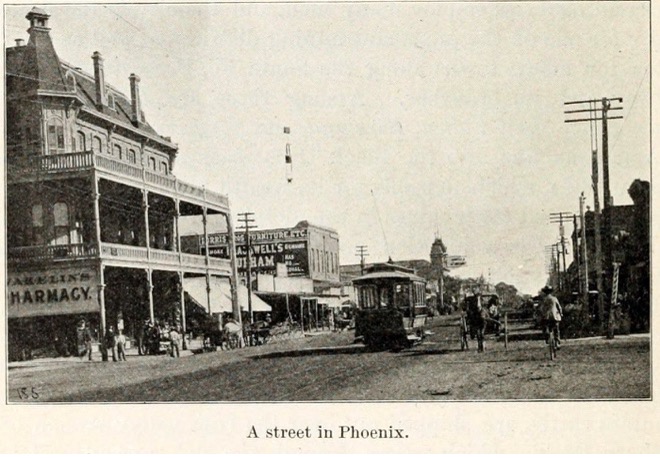

Capt. Robert Peattie (SF Chronicle) 1905

Capt. Robert Peattie (SF Chronicle) 1905

The Leicester Castle returned to sea on July 27, 1902. In the opinion of its Captain, three new Americans appeared to have no experience with actual sailing, and they spent the first days vomiting and complaining about what was asked of them: The owner of the confiscated revolver, the “stoutly built and smooth shaven” W.A. Hobbs, 27, claimed to hail from Litchfield, Illinois and had been coached to falsely list experience on a previous vessel (the Crocodile) in order to rate the pay of an able seaman; Ernest Sears, 21, a runaway farm boy from McKey, Oregon, claimed to have worked the Grant; while James Turner, also 21, said he was from Ida Falls, Indiana and had sailed the Shenandoah. These men, though novices at sea, would end up united by their unhappiness aboard a makeshift raft.

The Leicester Castle was 273 feet long and it was noticeable when a crewman avoided his assigned work. After two weeks, Captain Peattie had seen enough to privately disrate each of these three Americans to ordinary seaman, at lower pay. After the Chief Mate discovered Hobbs uselessly “pulling on some ropes,” he asked him “what kind of sailor” he was, according to able seaman Wolz, to which Hobbs answered that he would find out “God damned soon” what kind. Hobbs stayed in his cabin refusing to work from August 2nd to 21st, citing headaches and fever, even after the Captain brought him quinine lotion and determined there was nothing wrong with him. After the Australian first mate, Oyston, called him a “loafer” and a “blood sucker,” and ordered him to turn out, Hobbs answered, “If you knew who I was you wouldn’t come and pull me out of this bunk.” When Sears and another sailor on duty neglected to ring the watch bell, Oyston threw a bucket of water at them from the poop deck along with the bucket itself. Things would come to a head on the night of September 2nd 1902.

___________________________________

Nathan Ward’s new book, Son of the Old West, will be released by Atlantic Monthly Press in September, 2023.

___________________________________

The Leicester Castle had reached South Pacific waters on its route to Queensland, and some crew slept on deck to find breezes. “It was beautiful tropical weather,” remembered the Captain, “every sail was set and drawing.” Capt. Peattie was quietly reading in his room before bed when one of the Americans, the farm boy Ernest Sears, appeared in the doorway to report an accident around 10:30 that evening. As recorded in the ship’s log, “Sears asked the Master [Capt. Peattie] to turn out as a man had fallen from the foreyard and broken his leg.”

Capt. Peattie was puzzled at the nighttime climbing that could have led to such a fall. But he moved into the cabin and lit a lamp to prepare his table for treating the injured man. When he asked Sears where was the sailor, he replied “Just outside.” Then, wrote the Captain:

Suddenly W.A. Hobbs…stepped into the cabin by the starboard door with a revolver in his right hand and a club in his left and with only the words ‘Now then Captain’ fired striking the Master [Peattie] in the left breast, the Master attempted to close with him and struck him once, but was fired at again and struck on the head with the club which brought him to the deck, where other two shots were fired at him and his head was severely beaten by the club.”

Article continues after advertisement

Peattie was shot four times before his second officer, J. B. Nixon, appeared at the port door in a singlet and white pants, drawn by the sounds of gunfire. Hobbs fired a shot to his heart, killing Nixon in the doorway with his own gun, which Hobbs had stolen from Nixon’s cabin, hoping to use it to retrieve his own Colt from the Captain. While the crew became gradually aware what had noisily happened, Capt. Peattie was treated by a crewman who had medical experience from the Boer War.

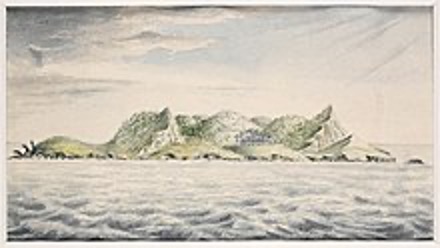

Pitcairn Island, home of the Bounty mutineers, 1814.

Pitcairn Island, home of the Bounty mutineers, 1814.(J. Shillibeer/ State Lib. New South Wales)

Able seaman Vincent Collins had shared the evening watch with Hobbs and Sears a few hours before the killing, and heard Hobbs ask second mate Nixon, “Are we going to call at Pitcairn Island?” Pitcairn was a remote rocky island in the South Pacific famously settled in 1790 by the original mutineers from the HMS Bounty, whose descendants were said to live there still over a century later. Even landlubbers like the three Americans would have learned from Boys’ Stories about the rebellion aboard the Bounty, its crew settling on Pitcairn after overthrowing Captain William Bligh. Hobbs may have pictured the island as a sanctuary where pirates might be forgiven and was disappointed in the mate’s answer that the winds would not quite allow them to “fetch it.” But not for the wind, Capt. Peattie had meant to come within five or six miles, where the islanders were known to row out and trade local fruits and vegetables with passing crews at anchor.

Following the sounds of shooting, Collins encountered Hobbs as he ran downstairs, excited and out of breath (and having emptied Nixon’s gun). After he disappeared again, there was the sound of hammering from the foredeck. The other crew kept away, waiting to confront the Americans at sunrise, as the three men hurriedly built themselves a raft, stealing some provisions (as well as another sailor’s boots and an overcoat) and at least one bucket of water. The Leicester Castle was more than 300 miles off Pitcairn Island when they escaped. It was unclear whether hearing about the proximity of the island had suggested the violent plan, since Hobbs had been overheard asking if the ship would be “calling” there. According to Vincent Collins, Hobbs had once told him he had been a cowboy in Mexico, Turner said he had invalided out of the American army in the Philippines, and Sears had run away from home “to go to sea.” No one knew if any of it was true beyond the part about running away from home.

Around 1:00 am they dropped their makeshift float over the port side, and the figures of three men were soon seen passing the stern; Wolz, who held the ship’s wheel, heard Hobbs saying, “Hurrah for the American flag.” Did he say anything else, Wolz would be asked, “Yes, sir. ‘All I am sorry for, I couldn’t kill every English cock-sucker aboard.’” Before vanishing, Hobbs shouted, “Take a drink at Juli’s,” referring to a Silver City mining camp saloon he and Wolz had discussed. As the Americans floated off into the dark, a dozen men went up to the poop deck with what guns they could gather on board, including Hobbs’ confiscated Colt from the Captain’s quarters. “The ship was still in the darkness,” recalled Vincent Collins. “…on hearing the voices we fired in the direction of the raft.” Lying wounded in his bunk, Capt. Peattie heard the guns on the deck.

Over the coming days, the men were thought dead, given the flimsiness of their mastless raft among the large sharks and ocean swells. “It was generally supposed that the three men had been drowned,” recalled Capt. Peattie, “and I never thought they would live till morning when I heard what the raft was made of.” From a quick inventory of what was missing, their float was assumed to be about twelve feet long and four feet wide, its planks buoyed by three cork cylinders torn from the forward life boat. Peattie would note in the ship’s ‘Slop Chest Book,’ beneath an earlier record of plugs of tobacco purchased by Turner and Hobbs: ‘deserted at Sea 3 Sep.’

The men and their raft were not seen again after their escape, but a passing ship, the Howth, later spotted bonfires on Pitcairn, signaling the presence of castaways the islanders wanted removed, its captain believed. But the winds prevented the Howth from investigating more closely, as the winds also did not favor the Leicester Castle’s visiting Pitcairn to learn if the three had somehow reached it without a sail.

At noon following the violent night, the body of 2nd officer Nixon was sewn inside his hammock along with an iron weight and “committed to the sea.” The wounded Capt. Peattie could not preside at the ceremony, but a week later was “healing quite nicely” without signs of blood poisoning and managed to hold on all the way to Queensland, by which time he could give a full account of the small uprising in which he nearly died. He would characterize the violence not as an act of classic mutiny (since the great majority had not rebelled), but more like piracy. The three Americans, who were barely sailors, had acted like “desperadoes of the worst class.” Newspapers would carry the story of the ‘cowboy mutineers.’

Capt. Peattie was recovered enough to command a new voyage aboard the Leicester Castle months after his near-death, accompanied by his two daughters. They left England for Vancouver in March 1903, and when the vessel put in there, the story of the “mutiny” by the Americans was revived in local newspapers. This drew the father of Ernest Sears to travel from his Oregon farm to meet the captain, and compare stories about his runaway son. After leaving Ontario, the Leicester Castle finally made a visit to Pitcairn Island, in the fall of 1903, a little over a year after the Americans’ disappearance.

One of Capt. Peattie’s daughters traveling with him, Jean Oliphant Barlow, wrote a remembrance of their day-trip to Pitcairn, where the locals “sighted us from the heights of the island, and about a dozen of the men had rowed out to us laden with all manner of luscious fruits, to barter with us for any old clothes or anything in the eatable line which we could spare.” The men were dressed in cast-off naval uniforms, white trousers, and caps from their previous trades. The daughters talked their father into going ashore with him, a difficult landing because of high rocks and rolling surf.

Pitcairn’s original “Bounty Bell,” was rung to herald the guests’ arrival. Jean Barlow admired the lonely island’s outbuildings (wood, thatched with leaves) and enjoyed the sweet scents of its flowers. The local women were barefoot, but wore “long, pinafore dresses falling from the neck right down to the ankle” and wanted to know how English ladies wore their hair. Capt. Peattie dined with Pitcairn’s schoolmaster, a London man who had married an islander, while the Captain’s daughters ate with a “Matron” descendant of one of the 1790 mutineers, “Miss Young,” who showed them the original Bible from the Bounty crew and signed a copy of her own history of the island. The visitors were served a variety of fruits, including tomatoes, which Miss Young had grown from cuttings given her by a passing ship’s crew. “She told us if they had only our British singing birds their island would be a Paradise,” Jean Barlow wrote. But Capt. Peattie would note something else lacking about the place: “I could learn nothing of Hobbs, Turner, or Sears.” As far as he was concerned, the story of his American highwaymen ended with their disappearance aboard their doomed, implausible raft, which had failed to reach the mutineers’ island.

II.

But two years after the shooting, in March 1904, one of the ship’s former crew, the German-born Christian Wolz, was traveling across Texas, looking a bit ragged but hoping to find new prospects in the West, when he claimed to have an astonishing encounter. Wolz had originally boarded with two of the Americans in San Francisco before shipping out on the Leicester Castle, and now saw a man he recognized as Turner at the depot in El Paso: “I went towards the depot,” he explained, “and I have met Turner and I said, ‘Hello,’ and he says ‘Hello.’ I says ‘How did you get here?’ ‘Oh,’ he says. ‘A schooner picked us up and brought us to San Francisco.’” Turner said he was headed for Idaho Falls, Wolz remembered, “That is all the talk I had with him.” But he also seemed to have told him that a man named Hobbs was living in Clifton, Arizona as a sheriff. When asked under oath why he ended the conversation with the mutineer, Wolz answered, “I didn’t feel like staying with him because he might have harmed me.”

Months later, on Christmas day, Wolz boarded a train at Douglas, Arizona and met a middle-aged stranger named William Sparks. The two had begun discussing some shipping incident then in the news when Wolz offered his own dramatic sea tale, “I told him I was on the Leicester Castle, then he began to ask me questions about it.” He became animated when Wolz told about his running into Turner near El Paso. Sparks, it turned out, was an Arizona Ranger, and also knew about Sheriff Hobbs, but not his past.

Indeed, Lee Hobbs was deputy sheriff of Graham County. The terrified Wolz had no desire ever to see the murderous Hobbs again, but word soon got out that a survivor of the Leicester Castle had turned up in Arizona. The Arizona Rangers held a grudge against Sheriff Hobbs, who had refused to hold some of their Mexican prisoners, releasing them during a recent flood; Sparks sent a cablegram to Scotland Yard, then he and his superior came to see Wolz, before arresting Hobbs in Clifton without explanation. “I first arrested him for turning those prisoners loose,” Sparks recalled on the stand. But once Hobbs was bundled into a stagecoach, he had seen a little more of his warrant. As his friends gathered near the stage window to ask the reason for his arrest, Hobbs deadpanned, “For murder on the high seas.”

Hobbs was brought to a dining room in a boarding house, where it was arranged that Wolz might discreetly look him over beneath an electric light; he identified Sheriff Lee Hobbs as the mutineer by his features, chiefly “a little mole on his left cheek.” This was the W.A. Hobbs with whom he had sailed from San Francisco, the murderer from the Leicester Castle. When his accuser was pointed out to him, Hobbs thought he had a scruffy look like “a Hobo,” and noted the thin soles of his shoes.

Lee Hobbs was held by the rangers for thirty days. An extradition trial followed the complaint brought by ‘His Britannic Majesty’s Consul-General’ Courtenay Walter Bennett, on behalf of the United Kingdom against “W.A. Hobbs, otherwise called and known as Lee Hobbs,” who “has been found and now is within the said Territory of Arizona.” Hobbs’s crimes included attempting to murder Capt. Peattie, “a human being in the peace of God and of His said Britannic Majesty.”

The Consul-General endured a stagecoach adventure from San Francisco through the Arizona Territory to attend the trial in Phoenix, in April 1905. It was said to be the most dramatic event yet in that city, and attended by dozens of Hobbs’ cowboy friends who wore their guns to show support. Despite Wolz’s testimony that this was the same Hobbs he’d seen during the violent voyage of the Leicester Castle, several witnesses suggested alibis for the sheriff; local newspaper stories cited arrests made by Sheriff Lee Hobbs at the time of the mutiny, and the man who ran the San Francisco boarding house where W.A. Hobbs had stayed before joining the Leicester Castle said the deputy sheriff was not the man he had known. (He then accepted drinks from Hobbs’s cowboy friends the rest of the afternoon.) While the killer was recalled as “smooth shaven,” Sheriff Hobbs testified about the history of his mustache, which he claimed to have worn all through the dates in question. Likewise, when asked if he had a mole on his face, the clinching mark for Wolz’s identification, he denied it, as did the judge inspecting him from the bench.

Capt. Peattie and Vincent Collins were summoned to a Bow Street police station in London, where they again gave their accounts of the deadly voyage. The Captain identified Hobbs’s revolver presented to him as the Colt he had held in his cabin and went over the ship’s log books to fact-check his memory, which seemed to need little refreshing about the violence. Collins also recalled the shootings and recited what little background he had gleaned about the Americans.

Capt. Peattie still bore the bullets from his ordeal when he set out from England, headed for the trial in Arizona, where he was eager to make the long journey to identify the killer of his second mate. The Captain was expected to be the last, most important witness. “The Captain and two members of the [Leicester Castle] crew are now on their way to America,” announced the London Weekly Dispatch in late April 1905, “where they will be confronted by the Sheriff of Graham’s County.” But the Captain was still en route to New York, where he would begin the overland part of the trek to Phoenix, when the judge pronounced Hobbs innocent. Had Sheriff Hobbs not had the sort of job where he made arrests that were reported in the newspapers, he might have been extradited for trial in England.

Lee Hobbs got on with his life following the ruling, but he also hired a lawyer from Tucson, who gathered together the trial transcripts and documentary evidence (some 700 pages) to prepare for a future damages suit against the British government. The materials were sent to the Territorial government at Phoenix to forward to the US State Department for Hobbs’s lawsuit. But this case was never brought before Hobbs died of consumption in 1914.

It is not hard to see why this story sank into obscurity, once the Arizona Hobbs and murderer Hobbs were ruled not to be the same man. As mutiny tales go, it was minor, since only three of the crew went over the side, and the Judge’s later ruling in Phoenix deprived the high seas drama of its denoument. I spent several months trying to prove poor Sheriff Hobbs guilty, receiving research help from archivists in Arizona, Washington, and Liverpool to gather all the materials from the trial and the account by Capt. Peattie’s daughter of their visit to Pitcairn Island, where the escaped Americans were not found.

Any movie of the episode would make Sheriff Hobbs guilty, for the sake of the story, but he wasn’t. The Judge was right, which makes it less likely that fellow mutineer James Turner survived in order for Wolz to blunder into him on an El Paso street. If Wolz was bribed or bullied by the Rangers into cooperation, Turner may have been added as a segue connecting one Hobbs to the other, against whom the Rangers already held a considerable grudge.

In fact, rather than plucked from the ocean, the three Americans may have ended life just as Capt. Peattie imagined, even hoped, in his less charitable moments: not lasting long enough on their feeble raft to exhaust their inadequate supplies, they were quickly drowned by the waves and taken by the sharks. As he noted, none of them had been much of a sailor.