Precisely when Sami al-Khoury departed this world remains unknown. As Lebanon’s foremost contributor to the French Connection, it is likely he retired before his country’s dissolution into anarchy. If he did live to see the start of the Lebanese civil war, it was very likely he stood to make a profit.

The outbreak of fighting in 1975 compelled multiple factions to engage in illicit commerce to finance their movements and secure territory. Smuggling operations thrived along the coast, creating lucrative markets for stolen cars, contraband cigarettes, and other illicit wares. Drug trafficking boomed as farmers expanded production and dabbled in new crops. Sami al-Khoury’s birthplace, the rough Bekaa Valley, assumed greater importance as the beating heart of Lebanon’s drug economy.

In addition to hashish, long a staple of the region, locals planted opium poppies and opened small conversion laboratories for the purpose of exporting morphine and heroin. By 1978, Lebanon was exporting an estimated 10,000 tons of hash annually. Drugs not produced locally were often trans-shipped from abroad. Shipments of Afghan-sourced heroin, some estimated in the tons, passed through Lebanese ports between 1975 and 2000.

Lebanon’s immense global diaspora was integral to many of the crimes hatched during the civil war. Conspirators of Lebanese descent were identified as complicit in shady deals and money laundering spanning Australia, West Africa, the Americas, and Europe.

Meanwhile, leading political figures in Lebanon accrued shockingly large fortunes during the growth of organized crime. Members of the prominent Gemayel family, which oversaw numerous Christian militias in the civil war, netted annual income of $1 billion to $5 billion off the sale of hashish and other smuggled goods entering and exiting the ports they controlled.

Hezbollah, the Shia Islamist group, was established amid the hashish industry’s renaissance in the Bekaa Valley. From its ori-gins in the early 1980s, many of its earliest members hailed from villages and towns where hemp and poppy fields dotted the land-scape. Awakened and mobilized with the help of Syrian and Iranian agents, Hezbollah’s fighters threw themselves into combat, attack-ing Israeli occupation forces and foreign peacekeepers.

Their greatest coup came in 1983 with the detonation of a truck bomb that claimed the lives of over three hundred American and French soldiers. With Ronald Reagan’s War on Drugs in full swing, American commentators keyed in on the connection between the group and the narcotics trade emanating from their main base in the Bekaa.

Even though definitive links were not established during this early stage of Hezbollah’s existence, the fact that an Islamic resistance group, backed by the defiantly revolutionary government in Iran, was associated with drugs was an irony few observers could pass up. Ayatollah Khomeini, one prominent critic wrote in 1988, sanctioned the trade since it “served the dual purpose of debilitating the Great Satan and paying the bills” on behalf of its fighters in Lebanon.

Hezbollah emerged from the Lebanese civil war stronger than many of its rivals within the country. In forming a veritable state within a state in Lebanon’s south, its leadership gradually oversaw the expansion of its criminal enterprises. Through the assistance of supporters and confederates in various states throughout the world, Hezbollah developed an intricate web of companies and charities that helped it launder money and finance its activities.

A critical source of these funds was narcotics. Connections forged through the Lebanese diaspora brought Hezbollah into contact with cocaine producers in Latin America. Its brokers brought it into contact with other militant groups such as the FARC in Colombia, as well as newly established cartels such as the Zetas of Mexico.

Syria’s own collapse into civil war led Hezbollah to branch out beyond more “traditional” narcotics. The rapidly growing field of synthetic drugs found a home in territories claimed by Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad. Among the new narcotics to hit the market was Captagon, an amphetamine admixture. Though Hezbollah’s supreme leader, Hassan Nasrallah, denied any ties to the trade before his death, press reporting and expert analysis from the Levant suggests that Hezbollah engaged in the Captagon market as a regulator and exporter of the drug to various states in the region.

Revelations that Hezbollah profited from drugs were fodder for those who have heralded the rise of narcoterrorism across the world. Lebanon’s premier militant group, however, was only one of many to inspire this realization. The term was first used by the President of Peru, Belaúnde Terry, in 1983. For him, the brutal campaign waged by the Shining Path on counternarcotics officers and the country’s military was nothing short of narcoterrorismo.

Evidence from other war zones and states under siege made the concept of narcoterrorism globally applicable. The FARC collaborated with Colombia’s cartels. Chechen rebels and fighters loyal to the PKK taxed drug smugglers operating within their respective territories. There was also the case of the Kosovo Liberation Army, whose links to heroin trafficking prompted Serb officials to insist that they were fighting “bandit-terrorist activity” in their country.

Talk of a “terror-crime nexus” assumed new dimensions with the opening of the War on Terror. Western officials and journalists openly speculated that Al-Qaeda stood poised to exploit local under-worlds for their own potential gain. News editors and commentators mused over various nightmare scenarios, including joint plots that would see Al-Qaeda acquire nuclear material.

Meanwhile, clear patterns of evidence suggested that guerrillas in Afghanistan and Iraq were making the most of the aid provided by money launderers and illicit traffickers. It was estimated in 2006 that anti-coalition fighters in Iraq were generating anywhere between $70 million and $200 million annually in financing through a variety of illicit trades, including kidnapping, counterfeiting, and oil smuggling. If such estimates were correct, one US report declared, “terrorist and insurgent groups in Iraq may have surplus funds with which to support other terrorist organizations outside of Iraq.”

Terrorists, in truth, have always drawn strength from what may generally be called organized crime. Radical groups plaguing the West in the nineteenth century relied heavily upon smuggling and other schemes to obtain arms and money. The proliferation of re-sistance groups fighting Ottoman rule in the Balkans, for example, gave birth to a vibrant gun-running industry that endured beyond the First World War.

In addition to smuggling secondhand and stolen arms, Balkan traffickers dabbled in illicit tobacco sales as a secondary source of income. The growth of the Palestine Liberation Organization was certainly indebted to financial donations offered by Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states, yet after Yasser Arafat’s organization settled in Beirut before the Lebanese civil war, it, too, became engrossed in criminal activity: Alongside Turkish extremists like Abdullah Çatlı and Mehmet Ali Ağca, PLO agents found sanctuary in Bulgaria and partook in the country’s thriving heroin trade.

Despite these trends, terrorism’s rise through the second half of the twentieth century tended to be seen as distinct from the world of mafias. Nevertheless, the realization that terrorists behaved like gangsters provided a welcome pretext to attack and delegitimize the movements they represented. In the wake of the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland, official accusations that members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army had a controlling interest in Belfast’s drug trade aroused the ire of news commentators in the United Kingdom.

The tenor of this rage grew louder in 2002 when former IRA militants were arrested in Colombia for assisting the FARC in its campaign against the government in Bogotá. Even though the men were not charged with drug trafficking, one Brit-ish commentator surmised that the IRA possessed “an ambiguous attitude to hard drugs as it does not want it to be condemned for corrupting young people.” Former leaders of the IRA, as well as some scholars, have consistently cast doubt on the group’s involvement in narcotics.

There were still other cases where the line between terrorism and organized crime genuinely blurred to the absolute point of ambiguity. A particularly glaring example of the fuzzy divide between mafias and political extremism can be found in the life of Dawood Ibrahim Kaskar. Ibrahim, like so many gangsters before him, was a product of inauspicious beginnings. He was born in Mumbai in 1955 to a poor Muslim family from the north of India.

From the outset of his life, little separated him from the millions who eked out a living in the city. Dawood’s father, who attained a job as a policeman, was among the lucky ones. Mumbai’s culture of gangs and kingpins pulled Ibrahim in the opposite direction. In his youth, he thrived among the networks of pickpockets and smugglers who organized themselves according to neighborhood or along regional, confessional, or ethnic lines.

Success brought him into the orbit of a powerful syndicate led by Pathan migrants from the north. The Pathans introduced Dawood to far more lucrative trades such as moneylending, gambling, and, above all, gold smuggling. In time, he and his own small gang of followers graduated from petty extortion and theft to bank robbery.

At the age of twenty-five he muscled his way into the gold trade, an industry that brought him to markets beyond India. In the early 1970s he developed contacts in Dubai willing to buy gold and other wares. Business and real estate opportunities were rife in this burgeoning eastern metropolis of the newly independent United Arab Emirates, and Ibrahim seized them.

With some eighty-five percent of its population made up of immigrants, many of whom hailed from south Asia, Dubai’s historic and economic ties to India gave Dawood a base from which he continued to grow his interests and influence. He eventually expanded his operations into narcotics trafficking and sports fixing on a grand scale.

To this day, a fully comprehensive accounting of Ibrahim’s many business dealings, be they lawful or otherwise, remains elusive. Whatever the case may be, notoriety, as well as his purported support for India’s film industry, brought Ibrahim into the most elite circles of south Asian life.

As he entered middle age, Dawood Ibrahim’s career assumed monstrous dimensions. In December 1992, communal tensions in Mumbai spiked with the demolition of a historic mosque by Hindu nationalists. Months later a string of bombings exploded across the city, leaving 257 dead and hundreds more wounded. Mass arrests quickly prompted Indian authorities to assert that Dawood Ibrahim organized the attack as an act of vengeance. Indian officials further maintained that the bombings succeeded with the aid of the Pakistani intelligence service, ISI.

Demands for his extradition from Dubai purportedly compelled Ibrahim to relocate to Pakistan, where he may or may not continue to live. His disrepute grew by leaps and bounds a decade later when US officials implicated him in assisting in the terror attacks of September 11.

The precise role he played in the 9 ⁄ 11 conspiracy is not clear. An American congressional report from 2003 simply stated that Ibrahim had “found common cause with Al-Qaeda” and shared “smuggling routes with the terror syndicate.” Pakistan has consistently denied connections to the Mumbai bombings in 1993 and asserts it has not given Dawood Ibrahim sanctuary of any kind.

Mumbai’s most powerful gangster remains confoundingly understudied and underappreciated outside the subcontinent. His obscurity endures despite receiving the distinction of having been named one of the richest gangsters in history by Forbes (Pablo Escobar, according to the magazine, still retains the top spot).

Western bias may have a lot to do with his anonymity in much of the world. After all, there is little direct evidence that Dawood’s influence extends deeply into Europe and North America. His alleged involvement in illegal gambling and match fixing, for example, has been confined to domestic and international cricket events concerning India and Pakistan. The extent to which Ibrahim’s malfeasance does register beyond south Asia has largely concerned his supposed acts of terrorism. To this day, he shoulders the reputation of being India’s version of Osama bin Laden.

An uncomfortable truth may be at the heart of Dawood Ibrahim’s lack of recognition. Mafias, by and large, are creatures of the Western imagination. Why the world came to care about Capone, Escobar, and other mafia luminaries is the collective fear and intrigue they once inspired among Western officials and everyday citizens.

The case of Dawood Ibrahim may reveal some-thing about the extent to which terrorism has usurped the place of mafias within modern Western consciousness. Mafias, at various points, represented imminent mortal dangers to the integrity of states, economies, and societies in the West. The 9 ⁄ 11 attacks abruptly displaced this anxiety as Washington and its allies went to war with violent political extremism in various parts of the world.

As a smuggler, racketeer, and altogether thug, Dawood Ibrahim initially failed to register in the Atlantic world. It was instead as an ally of Al-Qaeda and as an instrument of Muslim extremism in India that he made his presence felt within Washington and other Western capitals. Here and in other cases, the extent to which a terrorist can be distinguished from a gangster may simply be a matter of perspective. That perspective tends to be from the vantage point of the West.

The concept of the mafia, one must remember, first entered popular consciousness during a far earlier age of violent extremism. Nineteenth-century news reports of the political upheaval in Sicily introduced the term into Western parlance.

Italy’s original mafiosi were similarly treated as expressions of political terror, not just crime. Their resonance as a symptom of the times grew in scope in parallel with other examples from separate parts of the world. By the end of the First World War, commentators perceived mafia-like traits among militants from the Irish Republican Army, Armenia’s Dashnaktsutyun, and other groups.

What altered the notion of the mafia at first derived from the meteoric growth of the global contraband trade, be it in alcohol or narcotics. The United States, more than any other force at work, shifted popular attention away from the early comparisons many made between Sicily’s honored society and political radicals. As the world collected itself in the aftermath of the Axis defeat, mafias became almost exclusively associated with discrete criminal enterprises devoid of any revolutionary goals.

The concept of the mafia, one must remember, first entered popular consciousness during a far earlier age of violent extremism.Syndicates like La Cosa Nostra (on both sides of the Atlantic), the Camorra, Marseille’s Milieu, and the yakuza tended to favor the powers that be. Subsequent groups, such as the Cali Cartel, Jamaica’s Shower Posse, or the ubiquitous “Russian mafia” also tended to favor political stability as opposed to revolutionary change.

What, then, changed? Has the world simply regressed or returned to the notion that there is no difference between terrorism and gangsterism? There may be some truth to this rhetorical question. What clearly has changed is the political economy that now envelops many radical movements. The breadth of the illicit marketplace has grown since the nineteenth century. The narcotics trade, more than any form of commerce, has become a vital resource for would-be militants.

Why terrorists involve themselves in illicit trades may not be a pure reflection of choice or utility. Hezbollah did not elect to become involved in drugs because of its attractive profit margins. It instead grew out of the illicit economic environment in which it was founded. The same may be said of the FARC, the PKK, and the Taliban.

This fact is indicative of how mafias are changing (or at least how they are viewed). Involvement in organized crime does not require excessive effort. The global prevalence of illicit commerce makes it both enticing and accessible for people and interests of various walks of life.

***

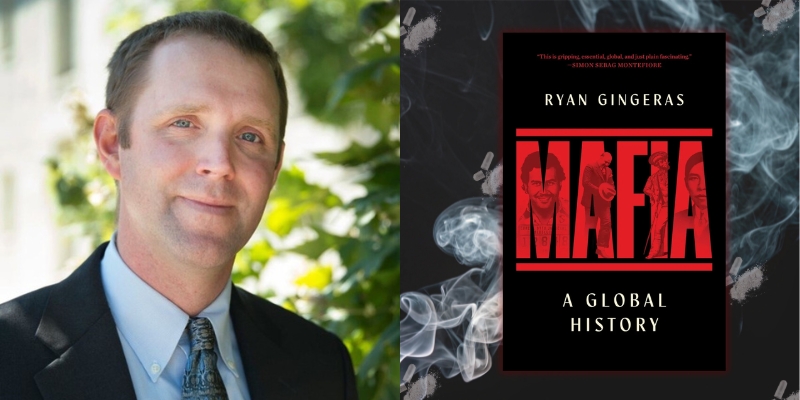

Excerpted from Mafia: A Global History, by Ryan Gingeras. Copyright 2026. Published by Avid Reader Press / Simon and Schuster. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.