One of the strange things about living in New York City is how half of your block could be nice, filled with decent citizens working steady jobs, while the other side of the street might be a creepy danger zone where drunks, junkies and mental defects dwell. On my old uptown block of 151st Street between Broadway and Riverside Drive there were two scary structures at the bottom of the hill that were sketchy for years. The first was 740 Riverside Drive, a once luxury six-story apartment house known as The Switzerland. Built in 1910, it was a towering building whose early advertising noted an elevator and spacious apartments; it also had a perfect view of the Hudson River as well as the colorful lights of Palisades Amusement Park.

The neighboring building was 745 Riverside Drive, an apartment house originally called Onondaga Court. Built in 1911, it too was a once fancy abode that lost its majestic appeal. Having seen vintage photographs of both buildings from the early 1900s, they were beautiful, charming and resembled urban castles. Decades back, if you were standing on Riverside Drive and 151st Street looking upward, you would’ve seen a clean building radiating with ambition, a domestic sprawl where doctors, real estate moguls and lawyers lived with their wives, children and obedient pets.

Still, by the time my family moved to the block in 1967, the two buildings had already transformed from regal to raggedy. Later when I read the brilliant novel S.R.O. by Robert Deane Pharr, a novel about a fleabag Harlem hovel called the Hotel Logan and its mostly drugged out residents, it was those scary buildings from my youth that I imagined.

NY Tax Photograph shot from Riverside Drive showing 740 and 745

NY Tax Photograph shot from Riverside Drive showing 740 and 745

Invisible Man novelist Ralph Ellison lived across the street from the two buildings at 730 Riverside Drive, aka The Beaumont. In the 2007 book Ralph Ellison: A Biography by Arnold Rampersad, the biographer noted that in 1970, the buildings were already a problem. “A flyer urging the residents of his building to unite against crime also dubbed his neighborhood the fastest deteriorating area in New York City,” Rampersad wrote. “The buildings at 740 and 745 Riverside Drive were the worst center of dope distribution, crime and violence in our whole area. A recent police operation had netted over 150 arrests. Muggers pounced on tenants in the lobby, the elevators, and even the upper hallways of the Beaumont at various times during the day and night.”

At night, before Ellison led his dog Tucka out into the dark for his walk, he donned a rough jacket and slipped a knife into his pocket. My friend Leslie Dominguez, who has lived in the neighborhood since childhood, also recalled how frightening the building was in the 1970s. “740 was a horror. I was never allowed to go inside, nor did I want to. It was a drug den (heroin), whore house and had all the alcoholic bums; that was a word we used a lot back then.” The other apartment houses on our block were mostly populated by families with kids, jacks and double-dutch playing girls and wild boys like me running down the marble floored halls, racing our bikes down the hill, shooting skellies and playing stickball in the streets.

Meanwhile 740 and 745 had become, as my old buddy Darryl Lawson called them, “the boogeyman buildings.” Lawson, a childhood friend and former neighbor, told me that his father saw a “butt naked white man” run out of 740 one spring evening. “The man was crying like a baby,” Darryl explained. “Some teenagers lured him into the building, mugged him and stole his clothes.”

Our mothers warned us to avoid even walking by those cursed constructions fearing that someone might stumble out of the shadows and snatch-up their child. Years later I’d wonder, “How did those buildings get so rough?” Beginning in the mid-1960s, New York City went through a transformation that included the town slowly going into decline and Vietnam vets returning home as dope fiends. Perhaps those buildings were a victim of those troubled times, or maybe the landlords simply neglected maintaining them once the neighborhood became a darker place.

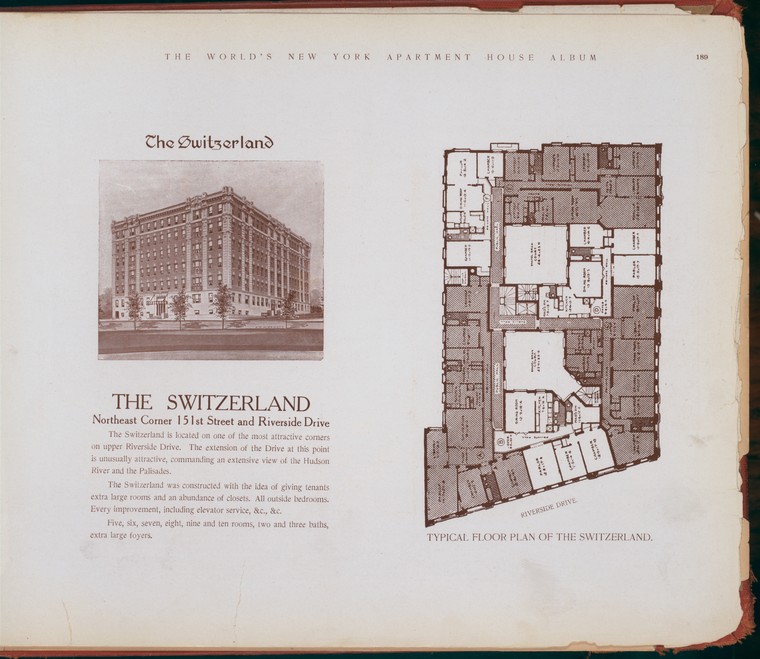

Vintage floor plan for The Switzerland

Vintage floor plan for The Switzerland

My first experience with the wickedness of 740 came one evening in the early 1970s when I heard that the beautiful dressmaker mom, who owned a neighborhood boutique on Broadway between 145th and 146th, was murdered in 740 by her boyfriend. She was fair-skinned and statuesque as a Grace Del Marco model. I often went to the woman’s shop with mom. On the racks were dresses and gowns hanging neatly. I recall sitting patiently as mom was measured. For some reason I remember a rainbow patterned sheer gown that Donyale Luna might’ve worn during that era. Decades later, mom couldn’t remember the murdered woman’s name, but hadn’t forgotten the story of her brutal death. “I don’t know if she lived in 740 or if her boyfriend did, but I remember your grandmother telling me what happened. It was a terrible thing.”

Grandma’s friend Miss Josephine, who often sat on our stoop at 628 West 151st Street and knew everything happening on the block, told her about someone who was pushed off the rooftop. “Poor guy was sitting in a wheelchair.” That same year a murdered 17-year-old girl was discovered in the basement. Twelve months later, in 1970, a dope fiend living on the sixth-floor named Ralph Garcia was charged with throwing two of his roommates out of the window a week apart.

According to my friend Leslie, who lived in a building up the block, she witnessed one of the falling bodies as it almost hit her neighbor. “That’s a very bad memory,” she wrote me via Facebook. “It was a Saturday afternoon in the summertime when that man fell or was thrown from that window. He barely missed a a Spanish older woman, as she stood on the corner. It was awful. His face was smashed. My sister and I saw it, and we still talk about it as one of those horrible childhood memories. My recollection was that he was thrown.”

Garcia spent two years in jail (The Tombs), but was found innocent of the gruesome crime when it went to trial. “A jury of nine men and three women returned the verdict in the second trial of 32‐year‐old Ralph Garcia shortly after midnight yesterday,” the New York Times reported February 3, 1973. “The 250‐pound former amateur weightlifter collapsed on the defense table and cried as the verdict was announced. ‘I feel wonderful,’ Mr. Garcia said after he reached his home. ‘Free at last! I’m home where I belong—with my family.’”

Perhaps the weightlifter didn’t toss those bodies from his window, but somebody did.

Though I’d never been inside 740 for any reason, my grandmother had a friend in 745, a plump woman named Miss Mary. We used to visit her and though the hallways were grimy and the elevator smelled like piss, her apartment was big, beautiful and had a magnificent view of Riverside Drive. Recently I used the memory of her place, where I could see “the changing leaves on the trees and the splendor of the Hudson River,” as a setting in my jazz fantasy “Water Music.”

One night in 1972 Miss Mary babysat for me and Carlos. Her nephew Drew was also there with his collection of comics that included a bunch of Daredevil books drawn by Gene Colan. That was my introduction to the world of Marvel, Colan’s art and the superhero Daredevil, a New York City protector. Later that year, unfortunately, there weren’t any superheroes around when an eleven year old Dominican girl was sexually molested and killed in the building. The child, who attended PS 28 on 155th Street had been absent from school. When friends came to her apartment after classes that afternoon, they found the door ajar and alerted an older woman neighbor.

What police found was young Isabel Soto strangled to death and laid-out on the floor of one of the third floor apartment’s bedroom. Her parents Rosalie Maldonado, a dressmaker, and stepfather Ruben Maldonado, a plumber, had last seen her at 7:30 that morning before they left for work.

The New York Times, always down for urban realism, reported on September 8, 1972, “The building has a self‐service elevator and one stairway. There is no lock on the building’s entry door. The hallways are shabby, with walls scarred by peeling paint and graffiti. Most of the residents are Puerto Rican, but the Maldonados were described as immigrants from the Dominican Republic.”

The next day the paper followed-up with another report. “An autopsy completed yesterday by Dr. John Furey of the ‘Medical Examiner’s office found that, the girl, Isabel Soto, had been strangled with a blue velvet neckband and that there were signs of sexual molestation. In addition to bruises around her neck, Dr. Furey said’ that there were bruises on the girl’s face. She died “several hours” before she was found at 2:30 P.M., he said.” Regrettably, I never read any stories of the animal that did the crime being captured.

On September 21, 1974, mom had taken me and baby brother Carlos down to our father’s place for a visit. While he and mom were in the kitchen talking, we sat in the living-room watching Emergency!, a show about firemen and ambulance workers in California. I had a crush on the head nurse at the hospital; years later I discovered she was Julie London, one of my favorite torch singers. That night on the program there was a huge industrial blaze that intrigued me.

“I’ve never seen a real live fire before,” eleven year old me said, speaking to nobody in particular. An hour later when we were on the #101 bus returning home, we saw and heard two fire engines racing up the hill at 145th Street. The sun had already set and the lights on top of the massive trucks illuminated the block. “I hope it isn’t our building that’s on fire.” Mom mumbled.

Exiting the bus on 151 Street and Amsterdam Avenue in front of the playground/basketball court known as the Battlegrounds, we could smell the billowing smoke from a block away. Mom walked fast and took a deep breath when she realized it wasn’t our building burning, but it was 740 where the flames were roaring from the rooftop and top floors. I can recall standing still and staring at the dancing flames.

Walking down the hill, we felt the wind blowing up from the Hudson. “That’s not good,” mom said. “That wind is going to fan those flames and make it worse.” When we walked into our first floor apartment, although our place faced the back, it was full of smoke. Mom pulled the fan out of the back closet, turned it on high and opened the windows. “Let’s go back outside until some of this smoke blows away.”

Me and Carlos raced down the stairs and out the front door where sirens blared. There was fire trucks on the block and at the bottom of the hill network news vans and Red Cross cars were parked on the sidewalk. A few of my crew that included Marvin, Kyle and Beedie were also there staring at the inferno. In the sky, a waxing crescent moon hovered over the Hudson.

I might’ve been only 11-years-old, but I’d been reading the newspapers since I was 8. I remembered well the year before a kooky dude named Benjamin Santana, who lived at 745, was accused of trying to set fire to 740. When NYPD detectives went to interview him, Santana accused them of acting with “Eisenhower and the F.B.I.” to steal his plans for rocket ship that was to carry him to the moon. The New York Times wrote, “When the detectives tried to calm the man, they said, he drew a knife with a 10‐inch blade and, telling the detectives they would pay for stealing his moon‐trip plans, lunged at them. He was shot five times.”

Miraculously, the man survived and was sent to Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital. As I watched the fire roaring through multiple windows I wondered if crazy Santana had made it back to complete the job. “Approximately 200 firemen and 40 pieces of fire apparatus were brought into action,” the New York Times later reported. “Firemen carried hoses up ladders, tied the nozzles with rope and directed streams of water into the upper floor by pulling on the ropes from the street.”

There were two hydrants on the block and both of them were in use. Water cascaded down the hill like a dirty waterfall. The fire burned until after 1 AM, but smoldered for many hours afterward. When we went back inside our apartment most of the smoke was gone. For years after I had a recurring dream of being trapped in a burning building, racing through the dark hallways looking for an escape as the flames continued to spread.

The following day I went outside early and the street was still chaotic. In 736 Riverside the Red Cross had set-up shop and treated the many people that needed it. Though I’d rarely seen anyone going into or departing 740, I was surprised when I read that there were 192 evacuees—110 adults and 82 children. “I’ve never seen any kids playing outside that building, let alone 82,” I said to my homeboy Beedie forty years later.

That Sunday morning in 1972, I walked over to 740 and looked up at the smoke streaked exterior. The smell of burnt stuff and dampness was strong in the autumn air. In many tales and religions, fire purifies and water washes away sins, but in the case of 740 I don’t believe that happened. “After that fire, when most of the building was empty, a few of us snuck inside 740 and had a clubhouse for a little while,” Beedie told me years later. That was news to me. I imagined them as a hood version of the Goonies. I was slightly hurt that I’d never been invited to the clubhouse, though I know I would’ve been too scared to enter.

Ten years later, when the dark days of crack crept into our community, all of the buildings on my former block went into drugged-out decline until the mid-1990s. In 1993 I moved downtown to Chelsea, though I still return to the old neighborhood periodically to visit friends and stroll down hill to those quiet Riverside Drive sidewalks remembering yesterdays gone.

When I discovered Ashcan school artists George Bellows and John R. Grabach, their paintings of grimy New York City tenements reminded me of 740 and 745. The last time I was in the hood was in 2018, and I passed both 740 and 745. Neither looked as scary as they once were; later, looking at listings on various real estate sites, the interiors have been modernized and the exterior no longer resembled a haunted house from a spooky Stephen King novel. However, in my memories and imagination, the boogeymen are forever.