As the author of several works of popular history, I knew when I began to write Hot Time, a mystery novel set in Gilded Age New York, that most of my characters would already be familiar to me from my extensive research on the period—Theodore Roosevelt, the gruff commissioner of police; Otto Raphael, one of the first Jewish officers on the force; and Minnie Gertrude Kelly, the first female stenographer hired by the NYPD. When I stumbled across William d’Alton Mann, a real-life magazine publisher who made a fortune extorting the crème of New York society, I knew I had found my victim.

Known for his choleric temperament, long white beard, and flaming red bowtie, Mann was fifty-four in August 1896, when the novel takes place. As Andy Logan relates in her excellent book The Man Who Robbed the Robber Barons, he had already been a Civil War colonel, an oil wildcatter, and the inventor of the sumptuous railroad “boudoir car,” a better-appointed competitor to the Pullman sleeper. But it was in 1891, when he assumed management of the weekly magazine Town Topics: The Journal of Society, that Mann found his true calling: extortionist.

Most of the magazine’s few dozen pages were devoted to short stories and light verse, reviews of recent plays and books, articles on art, music, sports, politics, and other items of interest to the leisure class. But the section to which subscribers turned first—with a frisson of either titillation or trepidation—was the department called “Saunterings.” Chronicling the activities of high society, the short entries included notices of engagements and marriages, reports of tea parties, racing meets, and debutante balls. But Mann, who wrote most of the items himself, under the pen name “The Saunterer,” would also aim ungracious barbs at the prominent: “Seldom does a brunette make a pretty bride, and Miss Maria Arnot Haver was no exception.” “The erotic southern novelist, Amélie Rives, has a kink in her hair that extends well into her brain.” “Miss Van Alen suffers from some kind of throat trouble—she cannot go more than half an hour without a drink.”

But even these zingers didn’t fully account for the column’s popularity. In “Saunterings” Mann would also lay bare the peccadillos and transgressions of New York’s storied Four Hundred, including romantic affairs, the births of illegitimate children, and bouts of venereal disease. Although he would never identify these individuals by name, his broad hints made them readily recognizable. And so he might include a victim’s home address or occupation, or confide: “The young man’s last name, incidentally, is the same as the title of the leading primate of the Church of Rome.”

Although no “respectable” person would admit to reading “Saunterings,” the column was a major reason that Town Topics’ circulation skyrocketed to 140,000 copies. And crucial to that success was one essential fact: the gossip was invariably true. Mann chose his sources carefully, drawing on the one hand from well-informed but cash-starved servants and on the other hand from society types looking to damage their rivals’ reputations or buy protection for themselves, and he insisted on confirmation by at least one additional source.

As lucrative as Town Topics was, Mann managed to make even more money from the articles he didn’t print. When he came across scurrilous stories about prominent figures, he would approach his intended mark close to press time and obligingly offer the opportunity to invest in “stock” in his company, or purchase “advertising” in the magazine, or extend Mann a “loan.” If the victims complied, the articles were pulled, and the contributors’ names were posted in a list of “Immunes” hanging in the Town Topics office. Over the years, dozens of Gilded Age luminaries bought Mann’s silence. Although it’s impossible to know exactly how much he earned from this extra-editorial work, the total was in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Mann’s blackmailing was eventually exposed when he was brought to trial, not for libel but for perjury. In 1904, while Theodore Roosevelt was in the White House, “Saunterings” included a vicious account of the Newport debut of the president’s notoriously independent daughter Alice. Though the teenager was never mentioned by name, she was easily identified, accused of “wearing costly lingerie,” “indulging in fancy dances for the edification of men,” “indulging freely in stimulants,” “flying all around Newport without a chaperone,” and “engaging in certain doings that gentle people are not supposed to discuss…. If the young woman knew some of the tales that were told at the clubs of Newport,” Mann rebuked, “she would be more careful in the future.”

Coming to Miss Roosevelt’s defense, the more genteel Collier’s magazine lambasted Town Topics as “the most degraded paper of any prominence in the United States.” A bitter public feud between the publications ensued, eventually resulting in charges of criminal libel—not against Mann but against Robert Collier, publisher of the esteemed weekly. Accused of lying in his testimony during the libel case, Mann was later charged with perjury, and though he was acquitted, his trial exposed his singular method of doing business. According to court documents, he received at least $76,000 from renowned Wall Street operator James R. Keene; $25,000 from William K. Vanderbilt, the richest man in America; $10,000 from steel magnate Charles Schwab; $5,500 from financier Jay Gould’s sons George and Howard; and $2,500 from J.P. Morgan, the nation’s most prominent banker and, in the estimation of many, its most powerful citizen. As one wag on the staff of the Louisville Herald put it, Mann testified that his purpose in Town Topics was “the elevation of society,” and he had indeed “held society up.” Even so, owing to incomplete evidence, he was never prosecuted for extortion. Did Mann ever express remorse? To the contrary. “My ambition,” he told a reporter from the New York Times, “is to reform the Four Hundred by making them too deeply disgusted with themselves to continue their silly, empty way of life…. I am really doing it for the sake of the country.”

Town Topics survived the Roosevelt-Collier scandal, but as the new century dawned and New York society became less obsessed with Victorian standards of behavior, subscriptions and advertising revenues waned, not to mention opportunities for blackmail. When he died of pneumonia, on May 17, 1920, at the age of 81, the man who had once terrorized New York society was insolvent. Mann’s daughter sold the magazine to a staffer, August Keller, who apparently hewed to Mann’s business model: In December 1931 the New York State Department of Securities announced an investigation of Keller for using extortion to sell stock in Town Topics. The magazine ceased publication the following month.

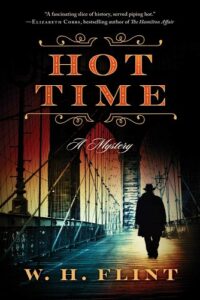

But if Mann got off comparatively lightly in life, I had other plans for him in my novel. After reading the publisher’s story, I knew that, thanks to the license of historical fiction, I could give Mann the kind of end that would have gratified so many of his contemporaries. In my version of the story, when J.P. Morgan is threatened with extorsion, he approaches an old family friend, police commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, and asks for his help reining in the blackmailing publisher. Not long afterward, a homeless newsboy discovers Mann’s body near the Brooklyn Bridge. Against the backdrop of Gilded Age excess, a historic heat wave, and the tumultuous presidential election of 1896, officer Otto “Rafe” Raphael insists on pursuing the case even after the commissioner orders him to desist, and even as the trail of suspects leads ever higher in Roosevelt’s own Republican Party. In Hot Time, at least, William d’Alton Mann pays dearly for his crimes.

***