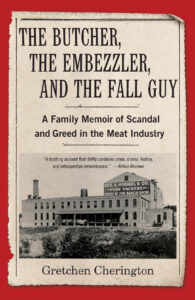

I never knew my grandfather, Alpha LaRue Eberhart; he died long before I was born. But I knew of him through my father’s stories, along with sepia-toned photograph albums from my dad’s childhood. Tall, with perfect posture, a regal nose, and a twinkle in his eye, A.L., as he was called, wore bespoke suits, enjoyed a bourbon and a fine cigar, and took his family and friends on sporting trips to the big rivers and lakes of northern Minnesota and Canada. They’d fish for their dinner, tell stories by the campfire, and sleep under the stars. It was he who endowed his children—along with me and my cousins—with our love of wild places. I knew he was known across the country as a motivating, yet kind, leader in the early meatpacking industry.

In 1901, George Hormel attracted A.L. away from the giant Swift & Company to join him in Austin, Minnesota where, together through twenty years, they’d build Hormel into an international brand. He and George Hormel were each big men with big ideas.

A third character on our family stage was Ransome Josiah Thomson. A wily, pointy-eyed, small man, Ransome (nicknamed Cyclone for his excess energy), grew up in his grandparents’ small pioneer home in northern Iowa. After graduating from high school and obtaining classes in bookkeeping and stenography, Hormel hired Thomson as a bookkeeper, then promoted him to comptroller. While Hormel and Eberhart were securing new markets for Hormel meats and ramping up its growth, Thomson spent most of a decade embezzling nearly $1.2 Million from the company coffers ($18 Million today). This was national news. With his stealing, he erected a hybrid chicken farm-amusement park in the middle of nowhere that attracted as many as 60,000 visitors from across the country on a given weekend.

By the time Thomson’s embezzlement was discovered in 1921, the Hormel company had nearly been brought to its knees and my grandfather was forced to resign. All these facts were known to me from childhood.

For me the real mystery at the center of this crime story was: who was my grandfather, really, and was he complicit in the embezzlement, as some rumors suggested? While I built a successful career advising CEOs and their executive teams on how to change their companies into places where both business and people could thrive, I watched executives through nearly forty years and came to see how men in power tick. I saw their ambition and their gifts. I learned about their fears. I knew how their strengths could sometimes be their downfalls. I watched how they used—or misused—their power. While crafting this family memoir about scandal and greed in the early meatpacking industry, I would bring both the heart of a granddaughter and the eyes of a consultant to the story. I would need both. To do justice to these men I’d never met, I needed to walk around in their skins, trying to understand their motivations decisions.

*

White collar crime—as well as con men—have been around forever. As Donald Cressy famously suggests in his “fraud triangle,” all it takes is three conditions: pressure, opportunity, and rationalization. Most of us have probably experienced at least one of these. Through nearly a decade, Ransome Thomson exhibited all three.

I believe his pressure was primarily internal—the pressure he’d long felt to escape a life of hard farm labor like that of his father and grandfather; the pressure to be more like George Hormel and A.L. Eberhart in their fine suits and executive offices; the pressure for status and power.

He had opportunity because he alone oversaw the mechanics of the Hormel accounting system. The company was growing fast. Thomson was a hard worker and eschewed vacations; he was smart, efficient, and easily trusted. He oversaw the transfers of money between accounts and between banks. None of the company’s bankers raised an alarm. When the accountants Ernst and Ernst were brought in to audit the books, they found no flaws. Even the federal government had eyes on the Hormel accounts during the first world war when it took some control of the production and distribution of food.

I can only speculate about Thomson’s rationalization, but it likely came from seeing those above him doing better than he and believing he deserved the same. Maybe a little cash siphoned off wouldn’t be missed. If he didn’t take it while cash was plentiful, when would he? But Thomson was impulsive and compulsive, too, and suffered from high anxiety. Like most con men, as the years went by without being caught, he became more and more emboldened.

While companies today may have better guardrails, white collar fraud continues. Harvard Business School professor Eugene Soltes’ terrific book What Makes Them Do It—Inside the Mind of the White-Collar Criminal details the likes of Bernie Madoff, Ken Lay of Enron, Dennis Kozlowski of Tyco, and Scott London of KPMG. Most executive fraudsters look like our next door neighbors. They often don’t think what they’re doing is wrong. They don’t set out to be criminals. Thomson, like those today, got away with his stealing under the eyes of skilled executives who missed the signs. Most of us have denied something we didn’t want to see. We revere “heroes” in our midst and we hold tightly to our myths about them.

In conversation with Soltes, I understood that if companies were to fully eradicate every possible malfeasance, most would cripple under the cost. If George Hormel and his board, on which my grandfather sat, called in the best accountants and heard nothing from their bankers across the country, perhaps there should be no felt shame. Embezzlements happen.

But the emotional trauma of this crime that led to my grandfather’s firing and cratered his wealth took up as trauma in my father and passed to me. My grandfather spent his remaining years rehired by big meatpackers and he never lost his legion of industry friends, but if our family’s American dream was born in Austin, Minnesota, it died there too, in 1922, siphoned off through the veins of Thomson’s embezzlement.

So was my grandfather a complicit in this crime? I’ve had to reconcile competing influences as I’ve come to terms with my complicated family history. While many facts in this case are easy to find, others were a private matter. Within my father’s literary archives at Dartmouth, I came across four cardboard boxes he’d kept of my grandfather’s personal letters and business documents in the late 1920s. As I pored through those boxes, I read my grandfather’s words and heard his voice. I could taste his bourbon, breathe in the smell of bass grilling over an open fire. I felt his strong love for his family and friends. I found myself treading lightly at the start, not wanting to sully my impression of my forebearer.

But we can’t write memoir that way. We have to dig in, press for answers from those who will talk to us, read through sources we can get our hands on. If the crime was what led to my grandfather’s firing, what was he guilty of?

What I learned, grappled with, and ultimately reconciled is a conclusion that is not black or white, right or wrong, good or bad. The story speaks to the complexity of men in power, their human desire to hold onto their myths and see what they want to see. Like most white collar crime—the space between these polarities is where the real story resides.

***