Adam and I did all the usual touristy things while in Karachi: Mohatta Palace and French Beach, restaurants and cafés and dhabas. One day, we went to Zainab Market. Adam was mesmerized. In one shop, he picked up a beautiful antique copper paan daan. I explained to him what it was even though he was examining and handling it as if he were more familiar with it than I was. I turned to the shopkeeper to ask how much. The shopkeeper took one look at us and instantly quoted the foreigner rate. Adam replied to him, in Urdu, that he liked the paan daan very much and asked if he could have it for less. The shopkeeper looked at Adam quizzically.

“Where is he from?” he asked me, and once more, Adam replied in Urdu.

The shopkeeper shook his head and spoke at length about what an honor it was to have someone from the West learn our language. He insisted that Adam take the paan daan for free. Adam refused and started forcing a bunch of hundred rupee notes the shopkeeper’s way, now initiating a kind of reverse bargaining, with the shopkeeper pushing the money back into Adam’s backpack and threatening to throw in a free pashmina for me if we didn’t accept his gift. Eventually, we accepted, and Adam left the shop misty eyed, mumbling about the “incredible hospitality” he had just witnessed. Finding himself the beneficiary of relentless kindness and warmth, and endless freebies, Adam used these words frequently during his trip, “incredible hospitality.”

Each time, it grated.

Did he not see, I wondered, that nobody else around him was being treated like a king? Did he not connect his whiteness to the special treatment he was receiving? He assumed, I suppose, that this country was just exceptionally kind to foreigners, to guests. I can tell you, though, that he would not have been treated that way if he were, say, Somali or Bangladeshi, Nepali or Sri Lankan. No. What Adam was witnessing were the remnants of a culture where once he was, by law, obeyed and pacified. That kind of “hospitality” was in fact a legacy of his people’s wrongdoing. Or maybe it went further back still; maybe it was this “hospitality” that gave colonizers the impression that they were welcome in the first place, to claim a land and people not their own. The truth is, even if Adam hasn’t spoken a word of Urdu, he could have had any door he wanted opened for him in Karachi. With red carpets laid out. And he seemed by this either moved to tears or completely oblivious. I didn’t want to be this way, but everything about Adam was starting to annoy me. Having to explain my city to a stranger, his delight at the differences, his patronizing horror at the poverty, his calling everything “magical.” All of it was starting to get under my skin.

Then, one day, I received a gift from Amma. Despite her excitement for a potential union and desperation to see me settled down, Amma offered me a kind of authorization, an encouragement even, to follow the quiet beat of my own heart over the deafening din of that ticking clock. It happened while I was at the dining table doing my subtitles. Abba and Adam were watching cricket on the other side of the living room.

My translation project that week was not a pleasant one. It was a big budget blockbuster set in medieval India, where for the bad guys, the filmmakers had drawn on every Islamophobic stereotype they could think of. I’d had to pause play pause play my way through the Muslim baddies, with their voracious and violent appetites for women, animals, power, blood, and money, saying the vilest, most heart-sinking things. Amma passed by just as the man on-screen was waving a bloodied sword in the air, putting on a bad Arab accent, and yelling “Allahu Akbar.”

“What is this?” she asked.

“It makes my blood boil,” I said.

I told her about the PAs who, after being given the job of creating “authentic” graffiti for the sets of Homeland, spray-painted “This TV show is racist” onto the walls. She laughed.

“I want to do something like that,” I said. “To write something like ‘this is historically inaccurate and highly toxic’ in the subtitles of this rubbish. We should at least have the right to an afterword or something. It’s like they think I’m just a translating machine. And what am I promoting by doing this? I’m basically complicit now.”

“You don’t have to do it,” Amma said. “Just quit.”

“Amma, I can’t keep quitting everything. I have to make something of my life.”

“You don’t quit everything.”

“I do. And you guys encourage it. How will I ever do anything that way?”

Amma was silent for a moment.

“You are doing something,” she said. “You can’t see it yet, but I can. It’s coming.”

I felt soothed by her words, a part of me still believing that my amma could tell the future. I found myself suddenly thinking of the Centre.

“You really think I’ll make something good of my life?” I asked.

“Not think. I know. It’s like a puzzle. One day the pieces will just fit together,” she said. Then, as if sensing danger, she added, “But don’t forget to recite Ayatul Kursi.”

“I won’t.”

“And . . .” she hesitated for a moment before continuing, “that’s more important than all this.”

She gestured toward the other end of the room, where Adam and Abba were watching TV.

“Chakka!” Abba suddenly exclaimed, throwing his arms up in the air. Adam clapped belatedly in response.

“Be settled in yourself first. And in your work. And with God,” Amma said. “That way you’ll never feel desperate.”

When I was a child, Amma had struggled. She’d been a young woman with nerves stretched tight by a never-there husband, hostile in-laws, and an unsupportive mother. There was a time, she once told my sister and me, that those taut nerves had nearly strained to a breaking point, but an absolute financial and social dependency had forced her to contain herself. She’d raised us with the intention that we never find ourselves in a similar situation. On top of this, Amma sometimes described her pre-married life as a kind of idyllic paradise, with pets and time in nature, games and laughter, cousins and friends.

“If I were a man,” she’d once said, “if I had the kind of freedom and independence they do, I would never get married. I don’t know why they do it.”

Maybe things like that had planted a seed in me. I didn’t have the restrictions my mother had had. I could, in some ways, “live like a man.” And so, I wondered, did I need to take better advantage of the privilege of my freedom? Would marriage mean, for me, too, the end of something?

In the comfort of the cocoon of my home, I began to wonder about the extent of the compromise I had made. No, I started to think. That fire I longed for. It existed. It must. Fine, maybe not dances in the rain and jumping into someone’s arms while they’re on a moving train, but the emotional equivalent of that stuff—love and respect and mutual admiration, and yes, heart flutters and bedroom sparks. Those are the relationships in which both partners grow. The truth is, even little Billee made my heart melt more than Adam did. I missed him terribly while in Karachi, even though Naima texted me photos of him daily, and I found myself thinking that maybe I’d picked the wrong flatmate to bring home with me. In this way, doubt accumulated on top of doubt, and it started to feel like I had brought this relationship home not for it to solidify but for it to dissolve.

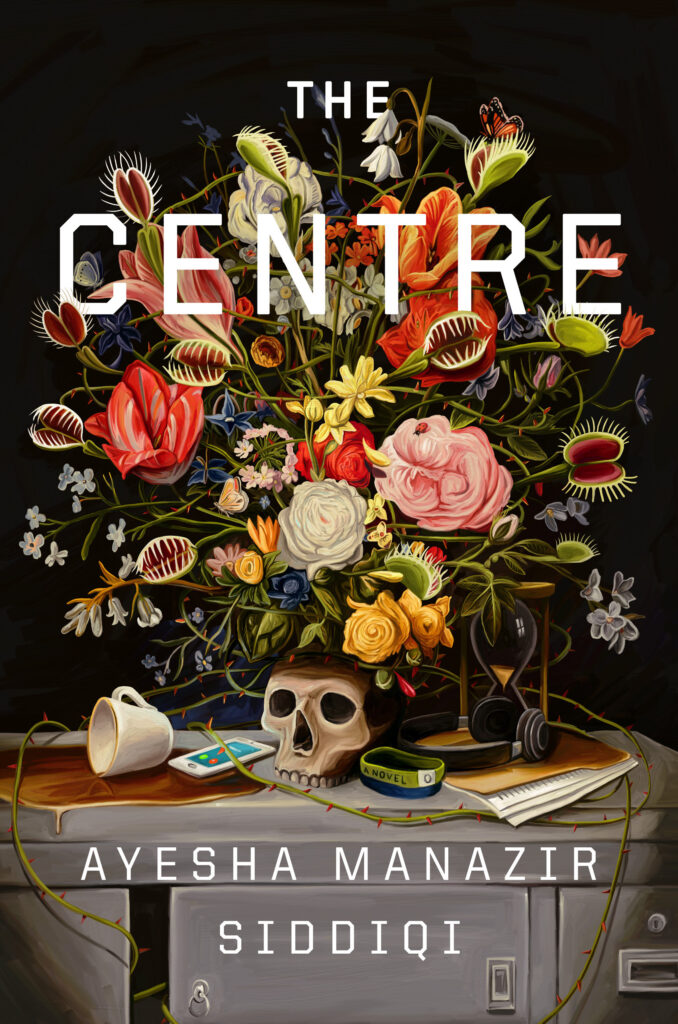

The Centre, I thought. The Centre could be the stepping stone I needed to reach the life I really wanted. To find a sense of fulfillment and meaning. To become a real translator.

But I forgot, of course, about the Ayatul Kursi.

On one of our last days in Karachi, while eating halwa puri for breakfast at Boat Basin, I told Adam I wanted to go to the Centre.

“To learn German,” I said. “Now that’s a real translator’s language. Can you imagine if I had access to German novels in the original?”

“Are you sure?” he asked.

“A hundred per cent. It’s probably the biggest market outside of English. And anyway, it’s so complicated, that language. Learning it will probably make me smarter.”

“It’s an intense experience, you know.”

“Come on,” I said. “If you could do it, I can do it.”

He hesitated for a second. “There’s something else.”

“Tell me.”

“Well, it sort of changes you, learning a language that fast.” “How?”

“Maybe I’ve just done it too many times, but it’s like, sometimes, you forget who you even are.”

“Forget how?”

“It’s hard to say. Maybe that would have happened anyway. I’m in such a different place now from where I started. Career-wise. Financially. Even you. It feels to me, constantly, like I was never meant to be here.”

“I think that’s an Adam thing, not a Centre thing.”

“It’s both,” he said.

“I know what it feels like, by the way, to not feel like you belong.”

“It’s not the same, Anisa. I’ve heard the way your parents talk to you. They’ve told you from the day you were born that you could be anyone you wanted. Me, every day I wonder. Sometimes I feel like I should keep a packed bag by the front door at all times, you know, in case I’m suddenly evicted from my life.”

He looked at me then, and I felt my heart soften. He touched the tip of his nose—our code for “I’m giving you a kiss right now” while we were out in Karachi. Then, when we got home, while the household was taking its afternoon nap, we locked my bedroom door and made love in a way that felt tender and true, but also like a goodbye. And once we got back to London, I asked Adam if we could take a break.

He seemed upset but didn’t protest. This made things worse; he acted as if my rejection were a justification for his own self-loathing.

“I understand,” he said. “I can be a bit intense, I know.”

“It’s not that. It’s just . . . I want to see where my head and my heart really are. I don’t know, Adam. Maybe I’m just meant to be alone.”

“You’re just trying to let me down easy.”

“It’s really not that.”

And so, Adam moved back into his own flat. He told me he’d given the Centre my details and that they would be in touch if I passed their background check. Completely unaware of the true nature of what I’d signed up for, I waited impatiently for their call.