Dear miss Howie

I saw a picture in the family circle and liked the looks of you. Thought I would like for you to correspond with me. I am single not been married but would like to if I could find the rite girl ha ha. Maybe that you. I hope it is. Please write to me. Send picture of your self and I will do the same. I would like to come up and see you if that all rite with you. I have been in Dakota a few years now and liked it all rite. How is crops. They look good here. I am 43 years old and have brown eyes and dark haire and weigh 175 and 6 feet tall. Write. Tell me all a bought your self. I will cease now.

A friend

When an August 1941 profile in the Sioux Falls Argus-Leader, the leading newspaper of the Great Plains state of South Dakota, described Edith Howie as an “unpretentious person, quiet, small-featured and trim,” with auburn hair, “deep blue eyes and…small, tapered…unusually beautiful hands,” Edith, an unmarried woman of forty-one years who lived quietly in Sioux Falls with her parents, had just published her maiden mystery novel, Murder for Tea, about the fatal poisoning of the town vamp at a literary luncheon. The novel had appeared in Three Prize Murders, a trilogy of tales which had received honorable mentions in publisher Farrar and Rinehart’s second annual Mary Roberts Rinehart mystery contest, named for America’s preeminent woman crime writer (one of her sons had co-founded the company); and it had been highly praised in the New York Times Book Review by Isaac Anderson, who pronounced it “as puzzling and as entertaining a mystery as one could desire.” (The previous year Elizabeth Daly had entered her debut novel, Unexpected Night, in the first Mary Roberts Rinehart mystery contest, in which she, like Edith Howie the next year, was a runner-up.)

Living up to her “unpretentious” reputation, Edith Howie wryly noted to her Argus-Leader interviewer, Lois Thrasher (who the next year would transfer to the Chicago Daily News, where she became night editor in 1945), that so far her greatest putative perk of fame as an author consisted of receiving myriad marriage proposals from importunate “mail-order bachelors,” like the gentleman quoted at the top of this introduction, who had eagerly espied Edith’s picture in The Family Circle, a women’s household magazine distributed for free at the once omnipresent Piggly Wiggly grocery store chain. Another of Edith’s male mystery admirers rang her up at home on the telephone one night, obviously inebriated and gushingly praising her books. When he failed to make any headway with the object of his fervent devotion, he rang off, angrily admonishing her, “I guess your books aren’t so good after all!” Edith, resistant to the charms of such men, remained single for the rest of her life. Yet she enjoyed an impressively full creative existence, allowing her to give rewarding expression to her twin true loves: professional writing and amateur acting.

Between 1938 and 1946 Edith wrote eight mystery novels, seven of which were published in the United States and the United Kingdom as well as other countries (there are some particularly nice Spanish-language paperback editions); and during this time as well, and for many years afterward, she was one of the leading lights in Sioux Falls’ community theater, both writing plays and performing in them. After her retirement from acting in the 1970s Edith reviewed local productions for the Argus-Leader, publishing her final review (The Fantasticks) in March 1979, just two months before her death at the age of seventy-eight. Although her career as a mystery writer was a brief one, lasting less than a decade, Edith during this time established herself as an American exponent of regional mystery and became as well a pioneer of the “cozy” detective story, where the tone remains light amid larcenies and criminal mayhem fails utterly to falsify the adage “murders end in lovers meeting.”

******

Edith Christy Ann Howie was born on July 12, 1900, the eldest of three children of William Henry Howie and Christy Ann McLean, natives of Ontario, Canada of Scottish derivation. Shortly after the couple’s marriage on April 12, 1899, they moved to Bradley, a town of fewer than 350 souls in the northern part of the raw, decade-old state of South Dakota, where Edith entered the world. William Henry Howie was the son of Cyrus Thompson Howie, an Oxford Mills farmer and Wesleyan Methodist, while Christy McLean was the daughter of Hugh McLean, a Maxville furniture store owner, Presbyterian and freemason. For four years prior to his marriage William had been a member of Canada’s Northwest Mounted Police and at the time of his nuptials he managed a cheese factory in Maxville. He carried on this latter occupation in Bradley, also adopting his wife’s faith, before moving with his growing family in 1905 to the city of Sioux Falls, South Dakota, the state’s largest city, located on the bank of the Sioux River in the far southeastern corner of the state, tucked between Minnesota and Iowa.

For many years William sold farm machinery for International Harvester Company. In this capacity he was often away on the road, plying his vital trade among Great Plains farmers, but his family became staunch members of Sioux Falls’ First Presbyterian Church, where Edith in the 1920s served as an organist. “Always an organist and never a bride,” self-deprecatingly comments a character in one of Edith’s later mystery novels, which was true enough in her case.

Edith’s father lived a more outwardly eventful life. For eleven months between June 1924 and April 1925, William Howie served, at the request of his highly-placed friend, Mayor Thomas Mckinnon, as chief of police at Sioux Falls, which then had a population of about 30,000 individuals. In 1925 Chief Howie reported that the police department had made 1135 arrests during the previous year, about 4% of the population. The great majority of these arrests were for minor violations of liquor laws and traffic ordinances, although there were also eight cases of burglary, seven of bootlegging, five of bank robbery, five of prostitution, four of grand larceny and four of forgery, as well as two rapes and an assault. Happily not a single murder was reported that year. “Nashiona (aka Sioux Falls) is small town Middle West and doesn’t go in for murders,” asserts the narrator of Murder for Tea with unintended irony. “It isn’t that sort of town.” Most of the other offenses with which Chief Howie and his men had to deal, like discharging firecrackers within city limits and bathing outdoors in the nude (i.e., skinny-dipping), admittedly strike one as disarmingly minor.

As Halloween approached in October 1924, Chief Howie issued a stern reminder to the city’s boisterous youth that pranks were only tolerated on All Hallows’ Eve itself, while the commission of acts of actual damage to people’s property would most definitely be prosecuted. Rather more seriously, Chief Howie the previous month warned local representatives of the Ku Klux Klan that his department was prepared to make “wholesale arrests” of any masked persons parading through city streets. During the Twenties, which saw a national resurgence of the Klan, South Dakota, like other Midwestern states, was, as one authority puts it, “plagued by cross- and circle-burnings, tar-and-featherings, and mass rallies and parades, including one attended by nearly 8000 people,” mostly with the goal of intimidating the state’s Catholic population. Perhaps it was this sort of thing which prompted Chief Howie to resign from office after having served for less than a year. He had been long retired from policing in 1934, when John Dillinger and his gang dramatically robbed Sioux Falls’ Security National Bank, in the process pumping eight bullets into a local motorcycle cop. Edith Howie recalls this incident in her mystery Cry Murder, when she has one of the suspects scoff: “Remember the time the Dillinger held up the bank here and they roared up, sirens screaming, and got picked off and lined up by the lookout outside with the machine gun? The Nashiona police—bah! They’re nothing to worry about!”

During his short tenure, however, the Chief had done his part to make Sioux Falls safe for law-abiding people like his daughters, who lived virtuous and placid lives in the city, presumably eschewing even illicit firecracker lighting and skinny-dipping, not to mention acts of grand larceny. In addition to her performances at the organ and piano at public programs (she confided that she had relinquished any hope of becoming a concert pianist on account of the “smallness of her hands”), Edith in the 1920s was active, along with her slightly younger sister Bessie, in the local chapter of the Delphian Society, an international organization which promoted women’s cultural education. For a time Edith, who attended writing classes at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion but never took a degree, succumbed to the vogue for archaic Old English names and self-consciously styled herself “Edythe,” but happily she abandoned this affectation.

During the Thirties just plain Edith Howie became active in Sioux Falls’ community theater and began publishing short stories in magazines, including Good Housekeeping, Ladies’ Home Journal, Liberty and the Canadian Chatelaine. In 1938 she completed her first mystery novel, Treeholme House. The novice mystery writer submitted the manuscript to Doubleday, Doran’s Crime Club imprint, who snobbishly turned it down, sadly, on the grounds, Edith later wryly confided to Argus-Leader reporter Robert Gunsolly, that “four of the five persons murdered in the book were servants.” Instead the tale appeared later that year, spiffily illustrated, in the Canadian magazine Maclean’s.

Undaunted by her limited success at mystery writing, Edith in 1939 began simultaneously writing two new mysteries, which she entitled Murder for Tea and Santa Claus Died. She submitted the two manuscripts to Farrar and Rinehart, who accepted both works in the spring of 1941 and published them within a few months of each other later that year, Tea in August in its Three Prize Murders volume and Santa in December (appropriately enough), with its title altered to the rather more anodyne Murder for Christmas. Presumably the publisher was leery of traumatizing, with Edith’s original blunt title, dewy-eyed innocents desirous of raking in their annual seasonal haul from Saint Nick.

Both Murder for Tea and Murder for Christmas are light “couples mysteries,” in which a young husband and wife are confronted with murder, respectively during a tea party at a literary luncheon and at a snowed-in country house Christmas gathering, where, reminiscent of Ngaio Marsh’s popular Seventies mystery Tied up in Tinsel, a man dressed up as Santa Claus is violently done to death. Tea takes place in Edith Howie’s fictional Great Plains city of Nashiona, an imaginative rendering of Sioux Falls, which also appears under the same name in one of Edith’s later mysteries, Cry Murder. Conversely Christmas is set in rural western New York State, perhaps as a sop to Plains wary editors, who once queried her having some of her characters travel twenty miles without encountering a single house.

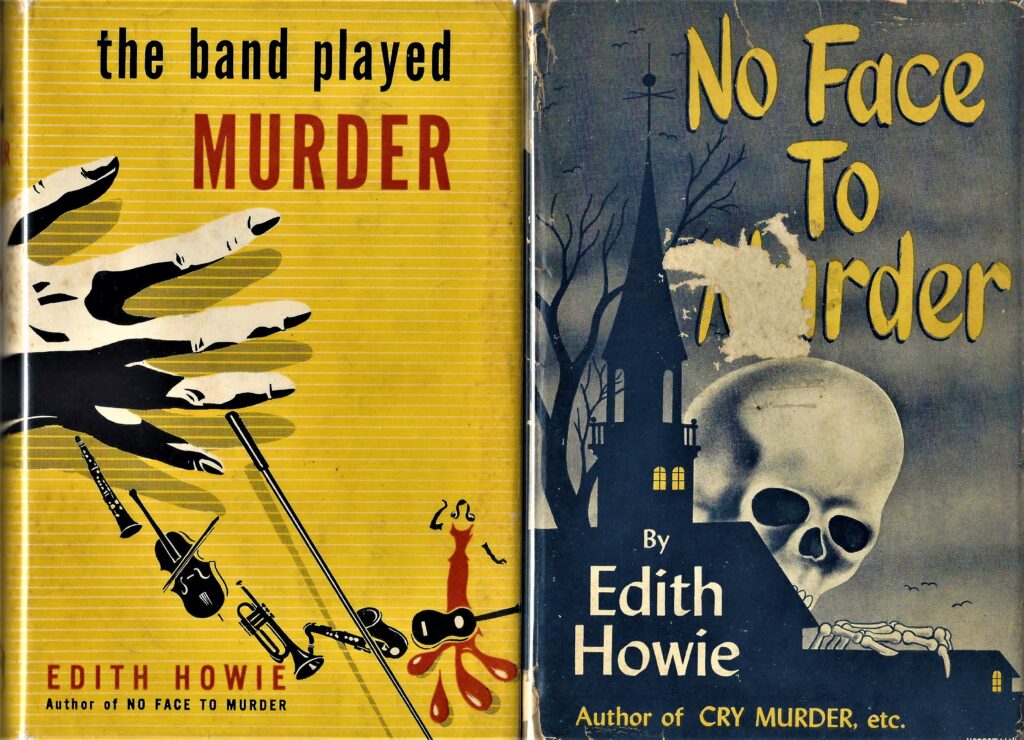

Edith worked on her first two published mystery novels in tandem, taking up one as she became stuck with the other, a process which she again employed with Murder at Stone House and Murder’s So Permanent, both of which were published in 1942, and No Face to Murder and The Band Played Murder, both of which were published in 1946. Cry Murder appeared singly in 1944. Edith also composed a stage version of Murder for Tea, which in 1941 and 1942 was performed under the auspices of Sioux Falls’ History Club, with proceeds going to support Red Cross War Relief.

Once she had her characters and their milieu set firmly in her mind, Edith would begin writing, even though she claimed that typically she had no notion when she started of who her actual murderer would be. She might change her mind on that matter more than once as she wrote. All of her mysteries are brightly narrated by chatty young women, either married or well on their way to wedding their crime-busting beaux by the end of the story. While arguably not the most rigorously plotted of Golden Age mysteries, Edith’s detective stories deliver the entertainment goods to likeminded readers, in the ingratiating manner of modern American “cozy” mystery writers like Charlotte MacLeod and with witty lines like “if a person can be said to make an entrance exiting she managed it” (Cry Murder) and “he not only carried tunes he ran away with them” (No Face to Murder).

Murder for Tea charmed reviewers. Aside from its laudatory notice in the New York Times Book Review, quoted above, the Durham, North Carolina Herald-Sun, declared the novel a “fast-paced, well-written, nicely-plotted mystery,” with “chilling and thrilling moments [that] come with scarcely a let-up.” Murder for Christmas, following hard on the heels of Tea, went down even more smoothly. “House party murders are among the most popular,” observed one crime fiction reviewer, and, indeed, Ngaio Marsh’s wintertime country house party mystery, Death and the Dancing Footman, had preceded Murder for Christmas into print by just three months. In the Saturday Review William C. Weber, aka “Judge Lynch,” proved especially praiseful of Christmas, summing up the novel as follows: “Exciting variation on family hatred theme, spooky from the start, fantastically characterized and satisfactorily deduced.”

Edith followed her 1941 mysteries with another pair in 1942, Murder at Stone House and Murder’s So Permanent. The former novel, set in rural New Jersey among the rural hunting gentry, was praised in the Saturday Review for having “[e]nough corpses for two novels and a likeable heroine.” Author and crime fiction reviewer Dorothy Quick, writing, appropriately enough, for the Central New Jersey Home News, deemed House a “detective story full of plot and romance” and guaranteed “the reader won’t be bored.” Quick added that “Miss Howie has all the essentials of a fine mystery writer,” a sentiment with which Isaac Anderson in the New York Times Book Review concurred. With House, Anderson admiringly avowed, “Miss Howie…has once more demonstrated a genuine talent for story-telling and mystification.”

With her fourth published mystery novel, Murder’s So Permanent, about skullduggery at a Midwest public library which imperils a young librarian and her fiancée, Edith maintained her high level of critical approbation. “Public libraries are dandy places for murders,” observed one delighted reviewer (almost as dandy as private country houses, one gathers). Isaac Anderson praised the novel’s “conspicuous merits,” which included “some very efficient sleuthing.”

In his reviews of Edith Howie’s later mysteries in the San Francisco Chronicle, prominent American reviewer Anthony Boucher emphasized their amorous underpinnings. Boucher himself was no romantic, to be sure, but he nevertheless enjoyed Edith’s smooth storytelling ability. “Ross Langdon doubles as love interest and detective….Good reading for the romance public…. (Cry Murder); “Randolph Garrison is more efficient as a lover than as head of homicide, but the telling and the church background…are pleasing.” (No Face to Murder); “Jewel thefts, love and marihuana tie into the murders of two girl vocalists with a big-time band….Colorful, unassuming and pleasant” (The Band Played Murder).

Five of Edith Howie’s seven published mystery novels are set in cities on the Great Plains, including the three reprinted this year by Coachwhip (and reviewed by Boucher above), which are her strongest books in terms of their regionalism: Cry Murder, No Face to Murder and The Band Played Murder. Cry Murder concerns killings and attempted killings which take place in Nashiona among a little theater group putting on a trial run of a play by a famed New York playwright (and former Nashiona native). The first murder, of hateful diva actress Nola Powers, occurs at the Olympia Theater, for which the author likely was inspired by Sioux Falls’ own Orpheum Theater, a beloved institution still standing today.

The Orpheum opened in 1913 and staged vaudeville acts until 1927, when it was sold and converted into a second-run and B-movie theater. By the time Edith wrote Cry Murder sixteen years later, the theater had fallen into disuse and been abandoned, but in 1954 the building was purchased and renovated as a stage theater by the Sioux Falls Community Playhouse, of which Edith was an important member. Mary Thorpe, the narrator and heroine of Cry Murder, memorably describes the Olympia Theater with WASPish middle-class distaste as follows:

The Olympia was an eight hundred-seat theater that, once in use almost exclusively for vaudeville and stock, had, with their passing, degenerated into a third-run movie house….Cheap hotels and cheaper restaurants surrounded it and its audiences were drawn quite frankly from that class of people who scorned to pay the ‘forty cents and tax’ price of first-run theaters and were willing to wait for their pictures. One visit there, during my noviciate in town, had been enough for me. The place had been poorly lighted and smelly, the screen a flickering disgrace. The seat to which I’d been ushered had been broken and sagging; I was suspicious of the probability of mice, or their big brothers, rats; while overhead the tireless dance of two creatures, which could have been none other than those anomalies of the animal kingdom, bats, had appalled me. My first visit had been my last.

Appropriately Edith stages the most atmospheric section of her novel here, when Mary goes there to meet Nola and encounters…well, read it for yourself and see! The case ultimately is solved by Mary’s love interest, handsome private detective Ross Langdon, although not without Mary’s help. Also contributing to the case is folksy Chief Hanover of the Nashiona police, whom Mary explains had “been a small groceryman before he picked off the plumiest of Nashiona’s appointive jobs.” Somewhat defensively Chief Hanover tells Mary and Ross: “[W]hile maybe you’re thinking I’m only a dumb old fogy who got the job of police chief in Nashiona by reason of being a good friend of the mayor’s, you want to remember I’ve held onto that job mainly by getting results. And results are just what I aim to keep getting.” Mary describes the Chief as a “short, stout, ordinary-looking man in a wrinkled gray suit whose waistcoat was crossed by an old-fashioned watch chain. He had thinning gray hair, a somewhat straggly gray mustache and eyes that were shrewd and sensible behind gold-rimmed spectacles.” The description matches that of Edith’s father when, at age fifty-two, he headed Sioux Falls’ police force.

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram delightedly described Cry Murder as “a typical murder mystery, the sort everybody enjoys,” with “appealing characters and situations and an atmosphere of eerie danger and suspense that marks the most satisfying type of mystery thrillers.” In its review the Argus-Leader spotted similarities between Nashiona and Sioux Falls, including the fact that with the advent of the Second World War, Nashiona’s population, like that of Sioux Falls, had virtually exploded. Observes Mary in the novel:

Nashionites consider that they dwell in a metropolis, which I suppose they do—it being the largest city within the border of two sister states—but nowhere has there been normality since Pearl Harbor, and Nashiona was no exception to the rule. Close against the boundaries now sprawled the mushroom growth of the huge army school….No one knew just how many soldiers were stationed there in the rows of wooden, tar-paper covered barracks but the number hovered somewhere between the twenty and thirty thousand marks….the soldiers formed a little city in themselves….sweethearts and wives…simply picked up their belongings and moved to Nashiona on the chance of finding accommodations that would enable them to spend a few more precious months with their loves ones….Every apartment, every hotel, every rooming house was jammed to its roof top. Rents had risen—temporarily, for a freezing order was imminent—to unprecedented levels. Tourist homes and cabin camps…were being rented upon a monthly basis. At the edge of town a flourishing trailer city had sprung up overnight.

It was all pretty breath-taking….

In real life, Sioux Falls in 1942 became the site of the Army Air Forces Technical School, which over the course of the war trained nearly 50,000 hostilities-bound men in radio communication, Morse code and aircraft identification. The school enabled Sioux Falls finally to recover from the lingering effects of the Great Depression, lessened the city’s Plains parochialism and launched a building boom which lasted well into the 1950s, as many recruits remained there after the war, married and started families. Much of this phenomenon is captured, albeit fleetingly, in Cry Murder—not the least of the novel’s felicities.

No Edith Howie novel appeared in 1945, but in January 1946 the author published No Face to Murder, which, like Cry Murder, is set during the war, in 1944, with wartime scarcity rather more advanced. (In Cry Murder, characters are still able regularly to consume waffles and grapefruit for breakfast and chocolate cakes with chocolate icing for dessert.) Face takes place in the Great Plains city of Dorchester rather than at Nashiona, but Dorchester, like Nashiona, sounds a lot like Sioux Falls, or possibly Sioux City, Iowa, about ninety miles south of Sioux Falls, where Edith’s sister, Bessie, a bank cashier, had moved and Edith frequently visited. The novel’s St. Thomas’ Episcopal Cathedral seems quite a lot like Sioux City’s St. Thomas’ Episcopal Church, imposingly constructed in the Richardsonian Romanesque style and completed in 1892.

In the novel double slashing murders, respectively of the church caretaker and the organist, incongruously take place at St. Thomas’ Episcopal Cathedral, in an opening surprisingly reminiscent of P. D. James’ lauded 1986 crime novel A Taste for Death, where two people, a homeless man and an MP, similarly are found dead at St. Matthews’ Catholic Church, their throats cut. Despite its uncharacteristically grim opening circumstances, however, Face ultimately bears a much greater resemblance to Agatha Christie’s The Murder at the Vicarage, peopled as it is with a charming cast of principal characters, including the young church secretary narrator, Tess King; church dean Alec MacDonald and his wife Ruth; Bishop Walters, who takes an interest in the case; and Randolph “Ran” Garrison, the handsome head of the Dorchester police department’s homicide division and Tess’ love interest.

Drexel Drake of the Chicago Tribune deemed No Face to Murder, which in my view is the author’s finest mystery, a “well-written yarn” with a “well-planned puzzle,” while noted crime writer Dorothy B. Hughes in the Albuquerque Tribune praised the “English atmosphere to this Midwestern mystery,” tipped off by the name of the city in which it is located, as well as the “authenticity” of its church setting and the “quite nice feeling to the whole…along with the bite of small-town nastiness.” For her part Avis DeVoto in the Boston Globe gave the novel an unqualified rave review, selecting it as her mystery of the week. “An unusually penetrating picture of a small community, with a double murder in a church as the highlight. Practically every member of the choir, around which the story is built, is a suspect,” DeVoto wrote. “Inspector Ran Garrison, assisted no little by his girlfriend, who is also the rector’s secretary, and a cooking bishop come through with all the answers, just too late.”

Ten months later came The Band Played Murder, Edith Howie’s final published crime novel. While with Cry Murder and No Face to Murder Edith had been able to draw heavily on her own familiarity with theater and church milieus, with The Band Played Murder she had to bone up on swing music, dance bands and “crooning” by reading back issues of Downbeat at the Sioux Falls Carnegie Free Public Library. Her protagonist and narrator, Connie Waring, another would-be concert pianist, is persuaded to serve as a last-minute substitute singer in Gale Ullman’s band. When murder beats the band at the city of Harriston during its annual Harvest Festival, Connie, who discovers the dead body, finds herself a person of interest to both local police and the actual murderer. The devoted Edith Howie reader can rest assured there will be ample love interest in the novel as well.

The Band Played Murder is another enjoyable Edith Howie mystery, pleasingly more sympathetic and informed about its subject than Ngaio Marsh’s Swing, Brother, Swing, which appeared in print three years later. “Reading Ngaio Marsh’s Swing, Bother, Swing,” wrote crime writer and composer Edmund Crispin disgustedly in 1966. “Poor, and if she’s going to try and write about jazz bands, why can’t she find out something about them? ‘Tympanist,’ indeed.” Edith did rather better in this regard than Ngaio, although like Cornell Woolrich in his notorious 1941 crime novella “Marihana,” the author propagates the myth that the drug can immediately transform people into murderous maniacs. (One guesses that Edith, like the heroine of her story, had never personally tried it.) The

Lexington Herald deemed Edith’s “swinging” novel “a bang-up yarn that does not drag a paragraph throughout the whole 243 pages,” while the Knoxville Journal avowed: “It’s an unusual background and a well written story told in the first person by a girl who is as confused by life in a dance band as most readers would be.”After Band came silence. Edith accepted a position as a librarian at the Carnegie Library and continued working on mysteries, but she never published another novel, criminous or otherwise. In 1951 Argus-Leader reporter Bob Gunsolley wrote that Edith was simultaneously writing not two, but three, mysteries, the most promising of which concerned an identical twin sister who, after awakening in bed with a choking sensation, later that morning learns that her twin was strangled during the night. Of course she sets out to find her sister’s killer. Apparently Edith completed neither this novel, nor the other two which she was writing (one of which took place among a horsey set in Kentucky bluegrass country), although by her own admission she remained a “rabid mystery fan,” getting first dibs on all the new mysteries at the public library.

After the deaths of her parents Edith in 1960 retired from the library and moved in with her sister Bessie at her foursquare Craftsman-style house in Sioux City, which still stands today. She remained active in Sioux Falls little theater, for decades indulging her own “taste for death” with parts in such mysterious plays as the chiller Night Must Fall, the farce Arsenic and Old Lace, the ghostly The Innocents (the stage adaptation of Henry James “The Turn of the Screw”) and a 1969 performance of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None, arguably the most renowned murder mystery of them all, where, nearly seventy, she played coldly pious spinster Emily Brent, who memorably gets figuratively stung by a bumblebee.

In real life Edith Howie passed away, a decade after this performance, at the age of seventy-eight on May 1, 1979. Her younger brother, William Lawrence Howie, a photography enthusiast who four decades earlier had advised her on the properties of potassium cyanide for her first published mystery novel, had predeceased her in 1961, while her sister Bessie expired in 1996, at the age of ninety-three. “Reviewer, Thespian Here Dies,” read the headline to Edith’s 1979 obituary in the Sioux City Journal, omitting mention of her mysteries until the body of the article, in which it was briefly noted that “she had eight books and 40 short stories published. Stories by Miss Howie have been widely published in the United States, England and Australia, and have been frequently translated for publication in Norway, Denmark and Spain.”

Having noticed that copies of Edith Howie’s novels were quite scarce and highly collectible, I wrote in 2012 about the author’s Murder for Christmas at my vintage mystery blog The Passing Tramp. Two years later Edith in Sioux Falls was inducted into Washington High School’s Hall of Distinction (she had graduated nearly a century earlier in 1918) and profiled in a series of articles by Argus-Leader features writer Jill Callison, who interviewed an elderly woman, Bev Halbritter, who had worked at the public library with Edith in the 1950s.

Edith, Halbritter recalled, was deemed intimidating by local high-school and college students who made trips to the library and she was initially “scared to death” of working with her with the elder woman. Yet soon she discovered that Edith “was the dearest, kindest, most caring person.” Finally in 2022, over eighty years after the publication of her first mystery, Edith Howie’s books are again back in print, as part of the remarkable ongoing reclamation of worthy crime writers from our past. Death for dear Edith came, it seems, not as the end, but an intermission.