There is a scene in Steven Zillian’s Netflix series Ripley where Tom Ripley and Dickie Greenleaf come upon an Italian woman sitting on the ground, rubbing her ankle. “Are you ok?” Dickie asks in Italian, crouching next to her. She explains that she has just been robbed and though she is not seriously hurt, she didn’t have money to pay for the taxi to take her home. Dickie helps her to her feet and walks her over to the taxi, which sits nearby, asking her where she lives. He pulls out a wade of cash, the large billed liras flashing near the driver’s window, and counts out almost half the bills before giving them to the driver. Tom looks on from a distance, the camera capturing his face in close up, his dubious expression setting the dynamics of the moment.

“That’s not enough,” the driver intones, and Dickie proceeds to give him all the cash he is holding. The woman says in Italian that he is the nicest American she has ever met. Watching with a romantic longing as the taxi disappears, Dickie translates for Tom what the woman just to told him.

Tom of course was aware of the con that had just happened. “You gave him enough to drive her to Rome,” he said. “He’s splitting it with her now.”

“You think?” Dickie wonders, looking surprised. Johnny Flynn portrays the character with an airiness that feels like he might just float away.

“Obviously,” Tom is incredulous, “What, a taxi’s just waiting there? It’s a scam. How can you not see that?”

Dickie then turns to Tom and asks: “Ah, so what if it is. It’s worth it to you for a pretty girl isn’t it?”

“Sure it is,” Tom snaps, adding, “I like girls,” while forcing a smile. We know Tom is a much better liar. Even Dickie looks at him with doubt. Director Zillian leaves us sitting there for a few seconds, lingering in the awkward silence between the two men before we watch them walk on.

Ripley gives us a Tom that is closer to Patricia Highsmith’s invention in the 1950s. Andrew Scott plays the character with a pitch perfect tone of a charming psychopath. In each scene his expressions barely contain the contempt he feels for those around him. His rage simmers beneath a likeable surface. Scott’s Ripley is nothing like Matt Damon’s portrayal in Anthony Minghella’s 1999 film, who is pretty and ingratiating, and whose only crime seems to be that he loved Dickie too much. The boat scene murder comes about out of Tom’s frustrated unrequited desire for Dickie. Damon’s Tom wore his queerness on the surface, and we all knew it. Instead, Ripley has echoes of René Clément’s 1960 French film Purple Moon, with the beautiful Alan Delon giving us a distant and existential Tom who possesses little moral center and hardly a breath of queerness.

Zillian’s Ripley, with its black and white shadows and uncertainties, gives us a perfect noir conman: scheming and strategizing and always, it seems, looking for a new target to reinvent himself. Of course, this Tom could see the woman on the street was conning Dickie. He could spot a good con. His awkward response, “I like girls,” right after he berates Dickie for “not seeing” the con, is its own subtle joke. Tom’s sexuality is a performance that he tries to make everyone believe. But here, his queerness is muted against his psychopathic ambitions.

In my own work into the history of crime and queer experience, I’ve come across a number of Tom Ripley’s in the early decades of the 20th century. Blackmailers, grifters, and violent confidence men who populated the underworld and preyed on the reputations of the wealthier men they encountered. Like Tom, these men often came from working class backgrounds and had little to lose and much to gain in taking on risky schemes. And like Tom, their sexual desires were often uncertain and flexible to fit the con.

In the early 20th century, the underworld had a rich vocabulary for con games. Edward Sutherland recounts the complex vernacular for such games in his 1933 book The Professional Thief. A few examples: Duke was a scheme involving fraud at card playing. Lemon described a con of collusion in betting. And the curiously named Glim-drop involved a con that used an artificial eye. Perhaps a more well-known term was the Badger game, which involved sexual extortion by a woman who would lure a man into a hotel room or apartment. When another man, posing as the woman’s husband or brother barged into the room, shocked and angry, the demand for money began. Queer cons worked in a similar way. Called Muzzle or Mouse, these schemes began as a simple act of staking out subway bathrooms around Times Square. After spotting two men entering a stall together, the extortionists would barge in, and in their outrage, threaten to call the police until money or valuables were handed over. Sometimes, the third party pretended to be a detective, flashing a fake badge and demanding money to make the arrest go away.

The schemes became increasingly sophisticated. Why wait for queer men to arrive at some bathroom stall? Why not bring them to you? The gangs started to use lures or “steerers,” younger, handsome men who would draw a desirous victim into a hotel room, a comfort station, or a public bathroom stall and get the man into a compromising position before his muzzle partner barges in, appalled, outraged, and demanding money.

These muzzle schemes became so successful gangs would organize muzzle trips, with men working different cities for long periods of time. As the dread of public exposure and scandal was so great, targets were unlikely to go to the police for fear of being arrested. Homosexual conduct was of course a crime. “The muzzle,” Sutherland writes, “is one of the few rackets in which a go-back (second attempt) can be successfully staged. In some instances, two or three go-backs on the same man are successful.”

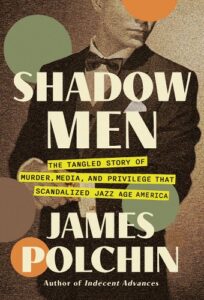

In 1922, the body of a 19-year old sailor named Clarence Peters found murdered on a road in Westchester County, New York quickly became a national scandal when the scion of a wealthy family, 31 year old Walter Ward, came forward to confess he shot the sailor. Ward claimed self-defense and described how Peters was part of a gang of blackmailers who were demanding tens of thousands of dollars from Ward. In my research into the Ward-Peters case for my book Shadow Men, the compelling question for investigators and the press was not who killed Peters, but rather what exactly was the relationship between the two men, and what was the secret behind the blackmail.

The Hearst owned New York American published sensational articles that suggested Peters and Ward were part of a network of queer conmen in the city. “Rich Men Met Poor Youths in Strange Group ‘The Wolf’ Led,” the newspaper announced on its front page. The article detailed the “secret circle of poor youths and men of wealth” that was dominated by a “piercing eyed man known as ‘The Wolf.'” This underworld circle of “extremes of social and economic life” met in parks, in Tenderloin resorts, and amid the “exotic atmosphere of magnificently furnished hidden apartments” around the city. Other leads suggested that Ward was the victim of muzzle scheme. When detectives went asking around the poolhalls of the Tenderloin, one informant told them that Ward was “shaken down” on two occasions that he knew of, though the details were slight. There were in fact other possible reasons for the blackmail Ward claimed.

The investigation into Ward’s claims led investigators to two known conmen: Nate Ross and his friend Joe Brown. Both had been arrested a few years earlier for extorting a Wall Street banker named Orville Tobey. Divorced and living with his mother and aunt, the forty-four year old Tobey met Ross along the street in Manhattan one October evening. Ross was broad shouldered and stood about 5’ 10” tall. Blond haired and fair complexion, his face tended to redden in the cool air, as it was that evening he met Tobey. Ross was enlisted in the Navy, and stationed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard during World War I. As was his habit during the war years when he invited sailors and soldiers to dinner with his family, Tobey invited Ross to his apartment on a number of evenings. The two would retire to Tobey’s study after dinner for conversation and, what Nate would later claim, sexual encounters.

Months later Ross brought his friend Joe Brown to dinner and soon the entire arrangement took a turn, as Brown began to threaten the banker. “I know what took place up in the apartment. I know you are a degenerate,” Brown told Tobey at one sidewalk meeting near his office. Brown threated to expose Tobey if the payments didn’t continue. For over a year he capitulated to the demands, but eventually Tobey went to the DA’s office. Ross and Brown were arrested. Their real names were Nathan Rosenzweig and Samuel Dreyfus, both from Russian Jewish immigrant families. The men openly admitted to the muzzle scheme when questioned. At first the DA made a deal: leave the city and he wouldn’t press charges. While both men agreed, they didn’t leave the city for long and were soon back at extorting Tobey. Eventually both were indicted and stood trial separately. After days of scandalous testimony, Dreyfus was convicted. Tobey, exhausted by the first trial and fearful of what Rosenzwieg would reveal about their evenings together, pressed the prosecutor for a plea deal, which Rosenzwieg agreed to. “I am convinced,” Tobey’s lawyer told the New York Daily News about Rosenzweig, “that he was a member or head of an enormous blackmail ring.”

Perhaps one of the more notorious real-life Tom Ripleys was that of Kenneth Neu. In 1934, the twenty-six year Neu left his wife and child and arrived in New York City in the hopes of becoming a singer. A native of Savannah, Georgia, Neu had dark hair and matinee idol good looks. At some time in the early weeks of his stay in New York he met Lawrence Shead, a thirty-five year old manager of a movie theater in New Jersey. Shead invited Neu back to his apartment where the young singer stayed for few days until one night the two got into a drunken fight. Neu hit Shead in the head with an electric iron after, he claimed, the theater manager “threw his arms around his waist.” We only have Neu’s recounting of the events of course, so what really happened in the apartment is not known. After Shead was struck unconscious and left for dead, Neu said he became “terribly frightened” and left Shead’s apartment. He was not too frightened to pack up Shead’s clothing, money, jewelry, and drive away in his car.

He would go as far south as he could get, eventually arriving in New Orleans and checking into one of the city’s luxury hotels. He registered under the name of Bill Williams from Jacksonville, Florida, and told staff he was on a three-months leave from the Chinese army where he was an aviator. In the hotel bar, witnesses remember his charm, his singing, and his large roll of cash he was prone to flash about. He occasionally found work singing in local clubs, leading the press to later refer to him as the “killer crooner.”

Not long after arriving in the New Orleans, Neu found his way into room 657 of the Jung Hotel. He was invited there by Sheffield Clark, a sixty-seven year old businessman from Nashville, Tennessee. Clark was described as an “old and honored citizen” of Nashville. It’s not clear what name Neu used when he met Clark, but it seems he didn’t flash his cash around the older man. The two had met in the hotel lobby, presumably as Neu was lingering about finding the perfect target. The two talked about politics and international affairs, suggesting Neu was still telling the story of his time in the Chinese army. Some days later he went to Clark’s hotel room to ask him for money. At some point Neu must have threatened Clark, only angering the older man. Clark refused his request and told Neu to leave. Neu struck the man several times. He placed Clark in bed and pulled the sheet tight against his chin to make it look as if he were asleep. For the next two days, maids would enter the room, but leave quickly, believing Clark was asleep. Eventually, one maid tried to wake him and discovered the crime. Clark was only dressed in his underwear suggesting he was nearly naked when he had the argument with Neu.

Neu was eventually arrested and, much to the surprise of the police, admitted to both killings, recounting the details of the crimes with a calm demeanor. He seemed happy to have been captured. “If I’d gone on any longer,” he told the press, “I’d have killed somebody else.” The “most cold blooded killer” is how one newspaper described his confession.

At his trial in New Orleans, Neu wore one of Shead’s suits he had stolen. “Whatever is coming,” he told the court, “I’ll try to take it like a man.” Since he had confessed to killing Clark, his trial rested on the questions of whether the crooner knew what he was doing was wrong, and whether he was sane at the time of the killing. The prosecutor argued in part that Neu’s killing of Shead actually pointed to his sanity. That murder, he told the jury, “was what I might have done or you might have done under the circumstances,” adding that Neu’s response to Shead’s advances showed he was a perfectly “normal person.”

The jury agreed and found Neu guilty. He was sentenced to death by hanging. At his execution, the press described him as the “debonair night club entertainer” and the “singing slayer.” They also described how he was “nattily attired, his black hair almost glowing” as he stepped on the trap door of the gallows. “I like to have everything just right,” he told the press, “even a hanging.”

Watching Ripley conjured for me many of these real-life conmen whose exploits were shocking and tragic, and whose cons often profited from the prohibition and criminalization of homosexuals. Perhaps that is part of the pleasure of Tom Ripley. A fictional queer conman we can indulge in, knowing that when he says “I like girls” in that awkward way, it’s just part of the game.

***