If crime fiction reflects society, what can books published during wartime tell us about ourselves? Historical events obviously help shape our society and form our sense of cultural identity, and crime fiction is one mechanism for people to reflect upon that identity. While writing my own mystery series—set during the Second World War—I became interested in what crime fiction published in the 1940s had to say about a nation’s view of the war and their role in that struggle as well as the larger world.

What I found surprised me. A sampling of authors from various nations was revealing in terms of how the conflict was incorporated—or not—in crime fiction published during wartime.

Dorothy L. Sayers published very little in the way of fiction after Great Britain went to war in 1939. Of her well-known Lord Peter Wimsey series, there is a single short story, “Talboys,” written in 1942 but not published until years later.

Sayers did write a series of stories published in The Spectator during 1939 and 1940 (years later compiled as The Wimsey Papers) in which she commented widely on the war. These articles took the form of letters to and from members of the extended Wimsey family and were a vehicle for Sayers to convey her own opinions and comments about the war and how people were expected to behave during such a time. Revealingly, she has Harriet Vane (Lord Peter’s wife and an author herself) mention her reluctance to continue writing mystery stories while dictators committed mass murder across the Continent. This would seem to reflect Sayers’ own notions and is a fitting coda to the Wimsey saga.

Lord Peter himself manages a few letters from unknown locations abroad, where he and Bunter are on a secret mission. He conveys what he wishes his epitaph to be should he not return: “Here lies an anachronism in the vague expectation of eternity.” A fitting end for a character from the Golden Age of Detective Fiction setting out in his fiftieth year to do battle with dark forces threatening all he holds dear.

Agatha Christie published N or M in 1941, which featured her middle-aged spy duo Tommy and Tuppence Beresford. Set at the outbreak of World War II, Tommy and Tuppence— who in previous decades had been associated with MI-6, the British foreign intelligence service—are recruited to track down German spies and British fifth columnists (those who seek to weaken a nation from within). With some members of the intelligence services themselves suspected of being Nazi sympathizers, Tommy and Tuppence’s boss brings them back to investigate unofficially since they are unknown to most in the service.

The plot is a perfect reflection of Great Britain at the time it was written. Appeasers and Nazi sympathizers permeated government and society, as well as a wide-spread fear of spies infiltrating the nation. N or M handles this nimbly, bringing an English couple out of retirement to do their bit and bring down a spy ring. Satisfying stuff to a nation of readers standing alone against the Nazi hordes—especially since Tommy and Tuppence are not of the upper classes. Upper middle class, perhaps, but still closer to the common folk than Sayers’s erudite Lord Peter.

Of the 70+ works she published, N or M was the only novel in which Christie dealt with the war. Perhaps there was no further need to incorporate war themes into her work, which could only become more complex and deadly as the war continued. By 1942, it was beyond the talents or Tommy and Tuppence to tame the Nazi beast. Not even they could comprehend such massive and unbelievable terrors as were occurring in occupied Europe.

Was there a demand for war literature, or did the reading public want to be soothed by the annual release of “another Christie for Christmas” and her timeless tales of dependable detectives and certain justice? There is no evidence Christie ever wondered about the futility of writing mysteries as the war raged in the same manner as did Sayers. Sayers had her religious writing to focus on. Her radio plays about the Gospels, taken from The Man Born to Be King, certainly brought comfort to many suffering as a result of the conflict.

An odd footnote to N or M: the British counter-intelligence service MI-5 investigated Agatha Christie herself. She’d named one of the characters in Major Bletchley, which led MI-5 to wonder if she had a connection to the real-life, top secret Bletchley Park code-breaking center. All was forgiven when she confessed she had simply noticed the name while on a train journey.

Another British writer, Christianna Brand, published her first Inspector Cockrill novel, Heads You Lose, in 1941. It was a country house mystery and made no mention of the war clouds that must have been gathering as she wrote it. But in Green for Danger, released in 1944, she used the war to full effect as a backdrop to Inspector Cockrill’s investigation. A sense of high tension and dread suffuses the plot as V-1 rockets rain down on London and the English countryside. A murder takes place at a military hospital, and Cockrill is called in to unmask the killer before he or she strikes again. It’s a well-done puzzle plot, and the film adaption, released two years later in 1946, has been called one of the best adaptions of a book from the Golden Age of Detective Fiction. Indeed, H.R.F. Keating called Brand’s novel “Perhaps the last golden crown of the Golden Age detective story.”

But it is Brand’s depiction of V-1 rockets that bring the real terror to this tale. By 1944, the British people had thought they’d survived the worst of what the Germans could throw at them. There were no more bombing raids, the invasion of France was well under way, and Allied troops were approaching the German border.

Then came the V-1s. Silent after their motors cut out. Deadly and indiscriminate, they could plow into a busy street, a school, or an empty field with no warning. Soon thereafter, the V-2s began to fall, even more horrific in their speed and payload.

In Brand’s novels, the entrance of Inspector Cockrill to stop the murders may have provided some small reassurance that order would soon be restored. To today’s audience, the image of a primitive rocket may signal nothing more than an interesting backdrop to this story, but for my money, this is one of the most effective uses of contemporary war imagery. Audiences in 1944, living in fear of those same attacks, would have gasped.

Across the Channel, another writer of crime fiction was experiencing quite a different war. Belgian-born Georges Simenon was living in France when the war broke out, at which time he was named High Commissioner for Belgian Refugees in the department of Charente-Inférieure. After completing his government work there within a few months, he moved to Saint-Mesmin-le-Vieux in the Vendée on the Atlantic coast. Apparently, due to travel restrictions under the German occupation, he remained there for the duration of the war.

Simenon published several novels during his time in France, including The Hotel Majestic, Ticket of Leave (originally published as The Widow), and Maigret Returns. None mention the war, nor reference any historical event. They are set nebulously in the France of recent memory, and are empty of emotion, at least if one considers what was happening in occupied France at the time.

Simenon was suspected of collaboration, having been denounced by local farmers after the war. Like many French performers and artists, Simenon collaborated artistically to his benefit: he negotiated film rights to his books with German studios during the occupation. While most French men and women suffered during the war, Simenon grew rich and lived in comfort. After Liberation, the French Writer’s Union began to investigate his wartime activities. Before they could act against him, Simenon left the country, journeying to the United States. His connections with Nazi-owned firms resulted in a ban on any new works being published in France for five years. The restriction was hushed up and the public never knew. Ironically, Simenon was also investigated by the Gestapo because his name sounded like Simon, a common Jewish name. Simenon remained in the United States and Canada for ten years after the war.

During the post-war period, Simenon did write two psychological novels—”romans durs”—which dealt with events of the war years. Both The Train and Dirty Snow acknowledge the existence of the war and the violence which was part of it.

Meanwhile, across the pond, Raymond Chandler was riding high, his Philip Marlowe character wildly popular. Published in 1943, The Lady in the Lake was written shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entrance into the war. Chandler made a few passing references to the war, but nothing of substance. Nor did he mention the war again in his work until the 1950s.

Why, I wonder? In Marlowe’s world there is crime and murder, but not mass murder. People are beat up or arrested, but no one is drafted and sent halfway around the world.

Perhaps there was a demand for escapist literature during the war. Philip Marlowe is a wise acre, a hard drinker, and a tough guy who also enjoys chess and poetry. He makes all the right moral choices and knows how to avoid going down the wrong path. The perfect template for the American male going off to fight in a good cause—and a good psychological fit for what the Old World needed from the New. But then there’s Chandler’s own background. Born in the United States, he moved to London as a child, and grew up there. Back in the States, when the First World War broke out, he immediately enlisted in the Canadian army and saw combat in the trenches.

He never referred to his war experiences, except to say, two years before he died, “Once you have led a platoon of men into direct machine gun fire nothing is ever the same again.” Chandler certainly had the right to write or not write what he wished, but for all the deserved accolades he garnered, I still would have liked to read about what he saw and felt in France during that war. But Chandler, having seen more real war than most, kept those memories to himself, as did so many veterans.

The Second World War does make an appearance in his 1953 classic The Long Goodbye. An important clue hinges on an understanding of British regimental badges from WWII. Eileen Wade wears a badge she claims was given to her by Terry Lennox during his service in the Artists’ Rifles. Marlowe recognizes it as a Special Air Service insignia not created until 1947, several years after Lennox’s supposed death. Eileen Wade is also emotionally wounded by her experience and losses during the Blitz, which informs her character and motivation.

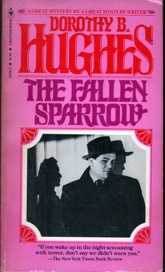

Over her career, Dorothy B. Hughes produced fourteen novels, all in the hard-boiled style. Several became part of the US government’s program for providing reading material to troops. The Council on Books in Wartime gave 122 million paperback books out as part of their Armed Services Editions program. Included among the 1300 titles was The Fallen Sparrow (1942), which starts with the quote, “. . . in a world at war, many sparrows must fall.” Not the cheeriest of thoughts for the soldiers, sailors, and airmen who read it as they went into battle, but truthful enough.

The Fallen Sparrow is the story of a veteran of the Spanish Civil War who escapes to America, only to be hounded by his limping torturer. It has Nazi agents mingling with Manhattan society and falls firmly into the who-can-you-trust category.

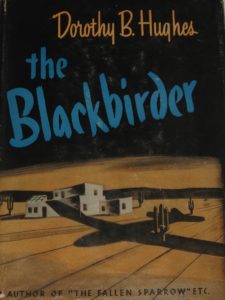

Hughes raises the paranoia of the who-can-you-trust bar with The Blackbirder, the 1943 tale of Julie Guille who is living in the United States illegally after escaping from Nazi-occupied Paris three years previously. Hiding in what she believes is safe anonymity in New York City, she finds herself the suspect in the death of a friend. Afraid of being revealed as an illegal alien, she takes to the road to find a legendary smuggler in the Southwest called The Blackbirder. What’s different about this novel is the gritty heroine (who always travels with her toothbrush, long before Jack Reacher is born) and the nuanced treatment of characters from the Southwest, where Hughes spent most of her life.

This is a great chase novel, with all the anxieties of the age laid bare. Julie Guille has her fair share of wits and courage, but will it be enough to survive? Who are her real friends? Is the man following her a Nazi, an English pilot, or an FBI agent? Does she dare trust anyone in a world ravaged by conquest and betrayals?

***

This is in no way a complete list of crime fiction published during the Second World War. But in these novels, there are two main threads to be witnessed. The first is escapism, in which no mention of the war is made. Timeless stories in a troubled time. The second is coming to grips with the enemy within; how to overcome weakness and corruption in a society suddenly called upon to demonstrate strength and determination. Whether in England, a midwestern college, or the Santa Fe desert, the goal is to recognize evil where it lives.

A lesson for us all.