Over the Christmas season in 1938, as the world glumly slouched toward war, Welsh author Howard Spring, book reviewer for the London Evening Standard, decided that he would relax by reading a couple of English crime novels. Heartily disliking both of the books—a detective story by Agatha Christie and a thriller by Sydney Horler—he wrote a column, which was published in the Standard on December 22nd, explaining why he reacted so negatively to them. His assessment of the Horler thriller, that it was dreadfully cliched, trite and predictable, did not create a stir—surely no semi-sophisticated reader ever expected anything otherwise by that time from the likes of Edgar Wallace wannabe Sydney Horler—and it need not concern us here. Spring’s scathing review of Agatha Christie’s detective novel, however, engendered a furious four-day flurry at the Standard, as the paper over four days in the first week of January published a series of letters both supportive and dismissive of the critic, along with his own provocative response. Among the chiding letters was a trio of missives from members of the Detection Club, Britain’s prestigious assemblage of many of the most notable detective writers in the country, including such luminaries as Dorothy L. Sayers, John Dickson Carr (an American then living in England) and Agatha Christie herself, who if not yet deemed the “Queen of Crime,” was about at the point where she needed to be thinking of getting a coronation robe fitted.

Sydney Horler

Sydney Horler

This flap between the critic and the crime writers about just what constituted acceptable criticism of a detective novel opens an interesting window on contemporary attitudes about detective fiction and whether it really merited respect as a literary form. Anticipating American novelist and critic Edmund Wilson’s more extended attack on detective fiction in his essay “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?,” Spring’s diatribe shows how some intellectuals held in utter contempt the detective fiction form, at least as it existed in the Thirties and Forties. (Both Wilson and Spring professed admiration for the late Arthur Concan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales.) Yet the vigorous response to his attack from detective writers and their supporters reveals that devotees of detective fiction were unabashed when it came to defending themselves and their reading matter of choice. Here in 1939, at the peak of the so-called Golden Age of detective fiction, fans felt no need to cower in corners when mystery writing came under criticism from lofty, lip-curling detractors.

Born in Cardiff, Wales in 1889, the son of a jobbing gardener (a frequent character in classic English mysteries), Howard Spring never felt the touch of a silver spoon in his childish mouth. With his mother having to take in washing to support the family after the death of his father, Spring left school at the age of twelve to supplement the family’s meager finances by working as an errand boy. After snagging a job in a newspaper office, he slowly worked his way up to the position of reporter, all the while taking evening classes at Cardiff University to improve his neglected education. In 1931, when he was forty-two years old, Spring was hired as book reviewer at the Evening Standard, a post which provided him with a regular stipend while he tried to launch a career as a serious novelist. In 1937, when he was nearing the age of fifty, he achieved success with My Son, My Son!, a novel later filmed in the United States. Three years later Spring published his best-known novel, Fame is the Spur, which was filmed in 1947 and 1982. So, when Spring composed his crime fiction review column in late 1938, he finally had, after nearly five decades of life, some proud consciousness of his own tangible literary accomplishment.

Morland

Morland

Spring, a working-class writer who has been described as “an influential middlebrow novelist and literary panjandrum,” believed in the artistic validity of the popular novel, accessible to broader swathes of readers, and he criticized remote, opaque, highbrow poets like T. S. Eliot and W. H. Auden. Both of the latter men, ironically, were keen fans of detective fiction, a hugely popular literary form, even writing theoretical articles about the stuff and, in the case of Eliot, devising rules for its writing; yet Spring, who considered himself more of a man of the people, had no use for the frippery fiction produced by crime scribblers. In the Evening Standard in 1936, he had scathingly reviewed a Nigel Morland “Mrs. Pym” crime thriller, The Street of the Leopard, a fetid farrago about the diabolical machinations of a pair of race gangs (Japanese and African) right in the very streets of London. He condemned the novel as utter hokum and “a first-rate example of those books which cause a reader with a grain of intelligence to distrust and dislike the whole class to which they belong.”

Hatred of Nigel Morland’s crime writing was one thing on which Spring and Auden actually agreed (though Eliot was more indulgent of thrillers). Indeed, the Detection Club had been founded in 1930 to a great extent in order to distinguish writers of rarefied, puzzle-oriented detective fiction, which appealed to the intellect, from thriller writers, mere purveyors of sensation who appealed, it was believed, strictly to the lower emotions, depicting the disgusting bowels of life, as it were. To be sure a number of detective fiction writers trafficked in thrills too, such as Agatha Christie, who, particularly in the Twenties alternated Hercule Poirot detective novels like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd with thrillers like The Secret Adversary and The Secret of Chimneys. (She even sacrificed Poirot’s dignity by marooning him, with his faithful, dim sidekick Hastings, into a conspiratorial crime shocker, The Big Four.) However, in the Thirties the gulf between detective fiction and thrillers widened, as detective writers sought to win greater literary prestige for their work. In class terms it was often asserted that detective fiction was read by notables like cabinet ministers and clerics, professors and prime ministers, while lowly thrillers merely kept housemaids and shop clerks up at night and drowsy in the morning.

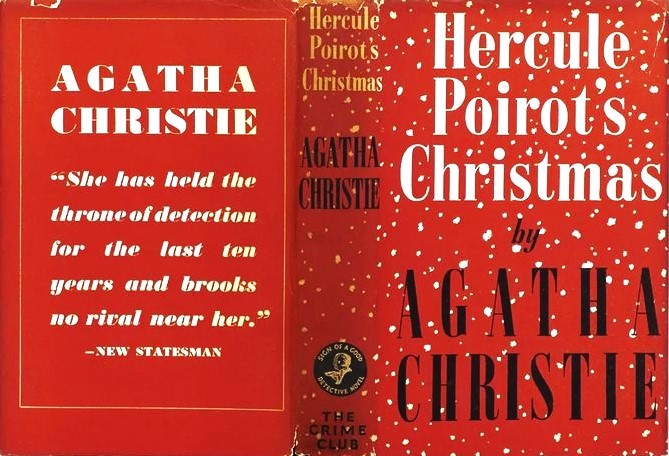

In his uncheerful 1938 Christmas review column for the Evening Standard, Howard ruthlessly sprang his trap, righteously calling down a pox on both houses of crime fiction, detection and thrills. He made this clear with his wholesale dismissal of Agatha Christie’s detective novel along with Sydney Horler’s thriller. For Spring so casually to bracket Christie with Horler, who among writers of shockers made the late Edgar Wallace look like Leo Tolstoy, was a mark of contempt indeed, a proverbial coal in the Christmas stocking. Apropos of this image, the Christie novel which Spring panned was her latest Hercule Poirot opus, Hercule Poirot’s Christmas, a Christie for Christmas which actually concerned Christmas—and murder, of course. Spring condemned Christie’s novel for having “a clumsy crime, a clumsy solution and an overladen narrative,” adding darkly that the book confirmed “my darkest suspicions about these detective novels.” He declared that if ever he felt the urge to commit murder, “I should try to make a neater, sweeter and somehow less farcical job of it” than had Christie’s careless killer.

Fair enough, one might say. Spring was hardly the first person to give a bad review to a detective novel, even one by Agatha Christie. (There had even been people who had not liked The Murder of Rogert Ackroyd.) But where Spring engendered controversy was when, at the very beginning of the review and continuing for a dozen paragraphs, he systematically detailed the solution to the murder, including both the identity of the murderer and the means of the murder (one of the author’s rare stabs at a locked room). This, in the view of the scandalized members of the Detection Club, went utterly beyond the pale, constituting a dagger to the heart of their very profession. If reviewers began willy nilly spoiling the plots of detective novels, who would actually read the things? For the fun of a whodunit, at least the first time out, is in trying to determine, well, whodunit. (For this reason, obviously I cannot go into detail concerning Spring’s substantive criticism of the plot of Hercule Poirot’s Christmas, though I will say that, despite the fact that the reviewer seems to me to land some logical blows on the technical soundness of Christie’s locked room gambit, I, like the late modern crime writer Robert Barnard, still consider the novel one of the Queen of Crime’s cleverest mysteries.)

First to pepper Spring’s line of defense was John Dickson Carr, then the corresponding secretary of the Detection Club and himself the undisputed master of the locked room mystery. In his letter Carr complained: “[In his review] Mr. Spring has carefully removed every element of mystery [from Christie’s novel]. He discloses (a) the identity of the murderer (b) the murderer’s motive (c) nearly every detail of the trick by which the murder was committed and (d) how the detective knew it. After this massacre it is safe to say that little more harm to the book could possibly have been done.” While Carr allowed that a “critic is at liberty to say what he likes about the merits of the book,” he insisted that it emphatically was not playing fair for that critic “deliberately to give away every secret of a detective novel, whose whole effect depends on keeping back those secrets until the end.”

To this protest Spring responded unapologetically, in a column the text of which ran under a picture of the critic impudently sitting astride the arm of a chair, that it was a critic’s duty to go into detail explaining why he did not like a book, detective novel or otherwise. If this rule were set aside for detective fiction, Spring riposted, “it is tantamount to an admission that these books have no relation to the art of writing and therefore cannot be dealt with by the normal methods of criticism.” Then he proceeded to concede that in his view crime fiction indeed had no relation to the art of writing. “[T]he cheap titillating tale of mystery or detection,” he declared loftily, offered nothing worthwhile to readers, but rather insidiously enticed, like an addictive drug, an “increasingly illiterate” British public away from the mentally wholesome and “lovely regions of true imagination where the great novelists and the great poets dwell.”

How obscene it was to waste time on Edgar Wallace or Agatha Christie, he pronounced, when one can read “Dickens and Thackeray, Flaubert and Hawthorne, Arnold Bennett and Somerset Maugham.” (Arnold Bennett actually wrote indulgently of Edgar Wallace’s thrillers, while Somerset Maugham was an avid reader of both detective fiction and thrillers, but it appears that Spring knew this not.) Of Edgar Wallace, who had had a street plaque erected in his memory, Spring wrote witheringly that “it is time it was said that [Wallace’s] output was of trash redeemed by hardly a vital spark.” Both thrillers and detective fiction were “injurious and mentally devitalizing to those who read them, because more often than not those who read them read nothing else.”

Letters from Dorothy L. Sayers and Helen Simpson, the latter of whom was a mainstream novelist like Spring who had occasionally dabbled in detection and was also a founding member of the Detection Club, followed Carr’s epistle a few days later. Simpson briefly explained the exact nature of Spring’s “offence”: “A detection story is primarily a puzzle, which the reader likes to put together for himself. What Mr. Spring did was to assemble the puzzle in public, thereby spoiling a good many people’s pleasure.” Simpson compared Spring to “that nuisance who at a theatre tells his neighbors just what is coming next, or who explains the tricks during a conjuring show.”

For her part Sayers, a former crime fiction for the Sunday Times and a leading exponent of the more novelistic detective novel, as it were, the so-called detective novel of manners, methodically explained to Spring how one can properly review a detective novel. She provided a review of an imaginary mystery called The Blood-boltered Pincushion, wherein “nothing has been given away to spoil such pleasure as the book may be capable of affording”:

The Blood-boltered Pincushion is an exceptionally feeble specimen even of the detective novelist’s alleged art. It is about a stockbroker found dead in a rabbit hutch, and the “great detective” is an analytical chemist who, on p. 59, shows himself unable to distinguish between a sulphate and a sulphite.

The criminals’ motive is psychologically improbable, and the murder-method a physical impossibility. The trial scene is disfigured, not only by the usual travesty of legal procedure, but by frequent lapses into bad taste and worse English. Indeed, the wooden characters use throughout such dialogue as was never yet heard on human lips. (Here insert brief specimen.)

Those who will swallow such defects all for the sake of a good “guessing game” will be shocked to find that no fewer than three clues have been deliberately concealed from the reader.

What of Evening Standard readers? With whom did they side, the critic or the crime writers? Among the letters the paper published, there was a fairly even divide of opinion, though the majority supported Spring, praising his daring in speaking out against the ghastly existence of crime fiction. Mostly lost by these letter writers was Spring’s original offense of gratuitously spoiling most of Christie’s mystery.

“Sincere congratulations on the denunciation of the detective dope pedlars and addicts,” cheered Sydney Jones Fabricius Maiden, an artist residing at Greystones, Chipstead, Seven Oaks, Kent, while Hugh Joseph Goolden, a barrister-at-law residing at The Bailey’s Hotel in Kensington (a great many Standard readers appear to have dwelt in Kensington and Chelsea) avowed: “Mr. Howard Spring has performed a public service in his denunciation of the detective ‘novel’ [note scare marks].” An evident wag by the name of Frank Acheson, who lived at Chesterfield House, an art deco block flats in Mayfair which had recently replaced a razed Georgian mansion, declared: “The trouble with those readers who are so terribly hurt by Howard Spring’s forthrightness in blowing the gaff (at last, thank Heaven!) on the high priests and priestesses of detective fiction is that they place too much importance on esprit de corpse.” Asserted Ian Monroe of The High, a block of flats on Streatham High Road in London: “Intelligent fiction readers will thank Howard Spring for his long overdue exposure of so-called detective fiction.”

Others defended the crime novel and condemned the critic, like Elise Murrell of Greenford, Middlesex, who wrote: “May I say to Howard Spring, ‘Tripe.’ In my opinion he is terribly doped by his ‘cleverness’ because education and time have made him unsporting and smug.” F. B. Hooper of 49 Wellington Street, Covent Garden accused Spring of “a gross breach of literary etiquette in his criticism of ‘Hercule Poirot’s Christmas’…equalled only, as an example of thoroughly bad manners, by his sulky apologia.” John Dickson Carr’s “admirably stated indictment,” he added, “errs only on the side of leniency.” An infuriated John Emanuel of 6 Eaton Rise expressed his doubt that “that great majority, for whom Mr. Howard Spring has such an overwhelming contempt, who read nothing else but detective novels and ‘thrillers’ have ever read anything so smug and complacent as Mr. Spring’s defence of himself and his theories.”

Lionel Ellis Gilman of Snargate, Kent and Purley, Croydon, an unmarried retired banker and ARP warden who was the elder brother of artist Harold Gilman (dubbed England’s Van Gogh), deemed John Dickson Carr’s “protest” against Spring’s review “moderate and justifiable,” while Spring’s “retort…has only made bad worse.” He tartly urged Spring, if he thought Edgar Wallace’s fiction was such facile trash, to try writing a thriller himself, and so “absolve himself of the necessity of any parasitic work.” Another Spring opponent, Peter Weissenberg of 2b Bickenhall Mansions, a Victorian block of flats in Marylebone, reminded the critic that the fine author J. B. Priestley had recently published a thriller called The Doomsday Men. “Think it over, Mr. Spring,” he advised. (Unfortunately, Spring had reviewed Priestley’s book earlier in 1938 and panned it, urging him to get back to writing something worthwhile.)

Who won the January 1939 correspondence battle between the forces of the critic and those of the crime writers? Ultimately, it was the crime writers, I would say, for crime fiction was here to stay, no matter how furiously its naysayers said nay to it. Today, eighty-five years later, Agatha Christie is as hugely popular as ever, while I imagine rather more people know of Dorothy L. Sayers than Howard Spring, though the latter’s two most famous books—massive, wordy, earnest tomes—are still in print. Edgar Wallace has made something of a comeback and there is even a wretched Sydney Horler volume available, courtesy of the British Library. Fans of Golden Age crime fiction realized something that the Edmund Wilsons and Howard Springs of the world did not (and even they admitted they liked the Sherlock Holmes stories): that it was fun and, taken in moderation, a harmless escape from the tedium and unpleasantness of everyday humdrum existence. Wilson and Spring and all the rest of their pious ilk really need not have concerned themselves unnecessarily with that.