The Wicker Man, which is 50 years old, has come to define the genre of folk horror.The term was popularized by British actor and writer Mark Gatiss in the 2010 BBC documentary History of Horror, referencing a 2004 interview with director Piers Haggard. Gatiss identified The Wicker Man as the third in the “Unholy Trinity” of films, which include Witchfinder General (1968), and Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), “[which] shared a common obsession with the British landscape, its folklore, and superstitions.”[1] Folk horror films use local mythology and traditions, including paganism and the “old ways” and are often set in rural, remote locations where a newly arrived outsider clashes with the mores of the local residents. .

The Wicker Man, directed by Robin Hardy, was adapted from David Pinner’s 1967 novel, Ritual, with notable additions, including an ending that earned it its cult following. So to speak.The Wicker Man is so iconic that in 2006 Neil LaBute directed a widely panned US-set remake starring Nicholas Cage.

In the beginning of the 1973 film, Police Sergeant Neil Howie (Edward Woodward) has received a letter inviting him to the fictional island of Summerisle, in the Outer Hebrides, to investigate the disappearance of a young girl, Rowan Morrison. Howie, a devout Christian, is shocked by the islanders’ unorthodox way of life. In his first two days, the Puritan sergeant witnesses a public orgy, a school where kids are taught the sexual underpinnings of May Day celebrations, and a pagan ritual that involves naked pregnant women jumping over a firepit. His search for Rowan is thwarted by the islanders’ denial that a girl named Rowan exists and lives in Summerisle.

At the Green Man Inn where Howie is staying, his abstinence vow repeatedly tested by the innkeeper’s gorgeous daughter, played by Britt Eckland, he sees a series of photographs celebrating the yearly island harvest, each year featuring a teenage girl dressed as the May Queen, with the most recent picture missing. After reading from a textbook inspired by James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, Howie concludes that the Summerislanders e inhabitants are preparing to sacrifice Rowan at the upcoming May Day festival, hoping that the human offering will yield a good harvest, after a year of failed crops.

He visits the castle of the aristocratic leader of the island, Lord Summerisle (portrayed with delightfully camp flair by Christopher Lee in his self-professed favorite role), who explains that his agronomist grandfather reintroduced paganism in Summerisle to make crops grow that can’t usually survive in harsh climates. Howie subsequently hatches a plan to rescue Rowan. He incapacitates the innkeeper, steals his traditional fool costume, and infiltrates the islanders’ costumed May Day festival.

But as soon as Rowan has been “freed” by Howie, she runs willingly into Lord Summerisle’s arms and asks if she “did it right” and he responds that she did it “beautifully.” The clueless policeman (and audience) then discover that the letter entreating Howie to search for Rowan, and the suspicious narrative of the inhabitants, as well as the staged “escape” scene, were all part of an elaborate ploy to lure him to Summerisle. Howie himself is considered the perfect human sacrifice to restimulate the failed harvest, as an adult visiting the island voluntarily, with the “power of a king” (because he represents the law), who is both a virgin and a fool. He is even dressed as a fool after having stolen the May Day costume of the innkeeper. A final ironic twist is that Howie, who makes frequent allusions to Christian martyrs, in the end becomes one himself, burned alive inside a giant wooden “Wicker Man.”The film hasn’t lost its power to provoke and disturb, remaining as terrifying in 2025 as it was in 1973.

The ending of the movie shocks in part because of the lack of violence in the first three quarters, which could have been a comedy. Much of the humor is derived from actor Edward Woodward’s wonderfully earnest pearl-clutching as he is exposed to increasingly ridiculous practices of the Summerislanders. Howie’s character is a fish-out-of-water prude scandalized by bawdy songs and folk remedies, which include a woman putting a toad in her daughter’s mouth to cure her sore throat. It is the humor, the musical sequences, and the decidedly weird but also seemingly harmless local customs that disarm us, ensuring that by the time we reach the conclusion, the brutality arrives out of nowhere.

Rather like the good townspeople of Shirley Jackson’s infamous short story The Lottery (1948) the terror lies in these easy-going pagan hippies’ willingness to enact a ritualistic sacrificial murder. The whole film plays out like an elaborate practical joke, with everyone in on it, including the “victim,” Rowan Morrison. Similar to Rosemary in Rosemary’s Baby, here the protagonist is kept in the dark throughout–with all the other characters ensnaring and trapping the hapless victim, and the viewer. Going beyond mere “red herrings,” and “scapegoats” the film’s ability to disturb lies in the inversion of the expected, and the “normal.” It is not the little girl who is the designated victim or women who are being exploited, but rather an adult policeman. The horror lies in Summerisle’s line, “The game is over […] the game of the hunter becoming the hunted.”

In this way, The Wicker Man also belongs to a type of horror film characteristic of the 1960s, the “justified paranoia” conspiracy-theory horror films, including Rosemary’s Baby (1967) and The Manchurian Candidate (1962.)

In the late 60s, British directors turned to new types of horror films, with idyllic British landscapes as the focal point, partly as a reaction to two decades of Hammer-produced films whose 19th-century stories replete with familiar Gothic characters, sets, and tropes were starting to feel stale. Witchfinder General and Blood on Satan’s Claw are both period pieces, with the former, set during the English Civil War, focusing on the 1645 witch-hunts of east Anglia, starring Vincent Price as the titular “witchfinder” in perhaps his most sadistic role. Blood on Satan’s Claw, directed by Haggard, takes place in an 18th-century English village where a demonic presence tries to take on physical form by afflicting young locals with fur and claws. Soon, the youngsters form a pagan cult and begin to turn on each other, in one horrific scene after the next.

Folk Horror films build on a much older literary tradition, which emphasizes the dark side of folklore and landscapes, as seen in the work of MR James (In The Ash Tree, which takes place in a remote English village, a woman condemned to death for witchcraft places a curse on her noble-born accuser and his descendants in their ancestral home), Arthur Machen (In The White People, a teenage-girl is ensnared in an alluring but ultimately dangerous occult forest world), HP Lovecraft (In The Hound, two bored friends summon an amorphous, ancient evil into their lives through graverobbing), and Shirley Jackson’s The Summer People, where an urban couple extend their stay in a lakeside cottage beyond Labor Day, only to be secretly sabotaged by locals who resent their presence.

These authors, among others, laid the groundwork for a cinematic tradition in which visitors intentionally or unintentionally meddle in a remote, wild place, disturbing the old customs of local inhabitants, and thereby bring destruction and death upon themselves.

American Folk horror was certainly having its own moment in the early 1970s—as seen in the work of Stephen King (Pet Semetary, Children of the Corn), and Thomas Tryon’s 1973-novel, Harvest Home. Although linked to Britain by their shared history and Puritan culture, the US had its own unique folk horror tradition reflecting its own national historical shame of witch trials, Native American displacement, and slavery.

If one were to consider the “Unholy Trinity” films as sociopolitical commentary (albeit on the other side of the Atlantic), Witchfinder General’s literal witch-hunts find parallels in the 60s red scare. Satan’s Claw and Wicker Man were made in the shadow of the Manson family murders, and both later films suggest a dark culmination of free-love culture, exploring what a group of brainwashed young people are capable of. The final, unforgettable scene in Wicker Man, showcasing a desperate Howie begging for his life, can’t help bringing to mind the chilling real-life ritualistic murder of Sharon Tate. In a case of horrific irony, Sharon Tate herself played Odile de Caray in Eye of the Devil, a folk horror film set in France.

The film therefore serves as an extreme example of the dark underside of hippy counterculture, an exaggerated warning about the dangers of collectivism and the immorality of the masses. Even putting aside the Manson family’s actions, the carefree hedonism of the 1960s did not always yield innocuous results. One need only consider the fates of the adult children who grew up in the artist colony set up on the Greek island of Hydra, to see how this experiment played out on the next generation, with countless examples of trauma, abuse, and neglect, resulting in high rates of addiction and suicide.

If horror films constitute mirrors of societal anxieties, The Wicker Man reflects several fears prevalent in the early 1970s, beginning with the distrust in technological advances, a special tradition in Britain going back to the 19th century Luddite movement. Even more poignant was a widespread internalized fear of female sexuality, newly liberated as a result of shifting cultural norms as well as increased access to contraception and the legalization of abortion in the landmark passage of Roe v. Wade (also in 1973), which no doubt made ripples across the Atlantic. In the end of The Wicker Man, even the adolescent girl, Rowan Morrison, is part of the elaborate con, and the dupe is a law-abiding adult man. A policeman solving a case himself becomes the victim. Similar to the unfortunate Jake in the following year’s Chinatown, here, too, the well-meaning lawman doesn’t understand the larger forces at play, gets in over his head, and his meddling has negative consequences. Like the “Chinatown,” of the film, Summerisle, too, is a metaphor for a place that exists outside of time, with its own rules, where outsiders who interfere are doomed to fail and ruin everything for themselves in the process.

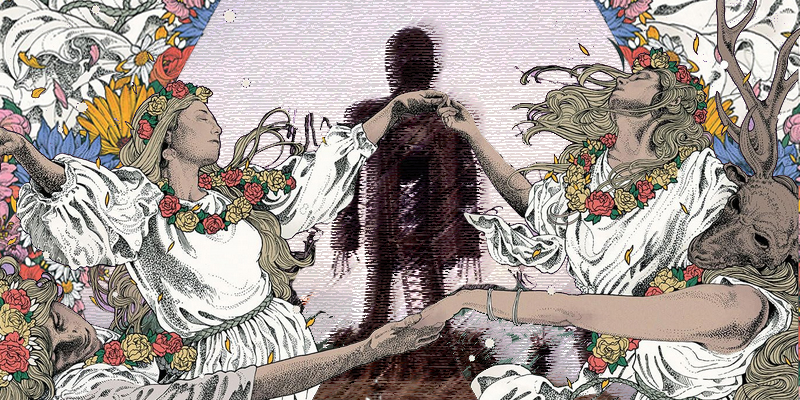

Fifty years later, Folk horror is having a worldwide revival on the screen, with critically acclaimed titles including Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015), Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019), Alex Garland’s Men (2022), as well as HBO’s True Detective (Nic Pizzolato and Issa López, 2014, 2017, 2023)

This phenomenon may be explained by the fact that folk horror is alive and well in crises that we were reckoning with 50 years ago and that continue to plague us today with renewed intensity—the “Failed harvest” of the Wicker Man can be seen as a metaphor for the consequences of pollution and environmental crises (that led to the establishment in the US of the EPA in 1970), and speaks to our own impact on the environment and climate change today. And, of course, The Wicker Man’s exploration of the darkest potential outcome of crowd psychology, where unenlightened groups embrace irrational and immoral ideologies, is more frightening than ever.

[1] Mark Gatiss, A History of Horror, BBC, Episode 2 2010