Jake Buchannan placed his palm on his eight-year-old daughter’s cheek, hooked a strand of chestnut hair behind her ear, and wished again that he could change the past. Em lay on top of her bed in her room, beneath a ceiling light needing two of its three bulbs replaced, and Jake thought her scar seemed a deeper shade of purple than usual.

Thirty-seven stitches. That was how many it had taken to sew his little girl up again. The scar wound from just above her right eye across her temple, then up over her ear, looking like a millipede forever crawling on her face.

I’m sorry, Jake thought. His therapist had told him to stop apologizing out loud, because it wasn’t helping his own healing process. Apparently, he had to learn to forgive himself first, and though Jake said he understood this, he didn’t really. Or didn’t want to. He wasn’t ready for forgiveness. Not from himself, or anyone else.

“I gotta go now, honey,” he said.

“For how long?”

“Just a few days.”

“I wish you didn’t have to.” Em’s words were better, but not perfect. The word didn’t came out slurred, as if she were just coming out of anesthesia.

“I know, me too. But this is a good job. Good money.”

“How much?”

More than it should be, Jake thought.

“A lot,” he said.

“Enough?” she asked.

That one word caught Jake off guard. There was only one way his young daughter could have an understanding of how much money was “enough,” and that was because she’d overheard the arguments. Arguments about the accident, arguments about the medical costs, and…god…arguments over whether their little girl had permanent cognitive damage. Em had certainly overheard things neither Jake nor his wife wanted her to hear.

They had argued less since Jake moved out a month ago.

“Let me worry about money, and you take care of your homework,” he said.

“Okay.”

He reached down and kissed her forehead, and his lips could feel the tight, rippled skin along her scar. “I love you to the moon,” he said.

“I love you to Mars.”

“I love you to Jupiter,” he said.

Jake knew what was coming next.

“I love you to Ur-anus.” Em burst out giggling, which always ended in the most wonderful snort.

He leaned in, smiling, and she wrapped her arms around his neck.

“Come home soon.”

Come home.

“I will, love. I’ll call you from Denver. Now finish your homework.”

“Okay.”

One last kiss, then Jake stood and left her bedroom, stealing a final glance of Em as he passed into the hallway. He instinctively began to head to the master bedroom to finish packing—until he remembered he was already packed and his clothes no longer existed in that bedroom anyway. His bag was in his car, outside.

Another memory fog. Perhaps this one was excusable… He and Abby hadn’t been separated long. But his memories were slipping, and whenever it happened, it filled his stomach with ice. He’d always been unable to recall his early childhood, but now his mind fuzzed over recent things. Conversations he had only days before, or appointments he was supposed to attend and simply forgot. At thirty-five, Jake knew he was too young for these memory slips to be occurring as frequently as they were, so whenever this happened, he’d stop himself and force a memory to the surface, as if to retrain the muscle inside his skull.

Yesterday’s outfit? he asked himself. A few seconds passed, then it came to the surface. Jeans, Ecco loafers, blue oxford shirt.

His therapist had suggested the memory loss could be stress related, or due to his poor sleep habits, adding he should see a specialist if he was truly concerned. Jake never did. He knew he could only get answers if he told the specialist everything that was happening in his life. This would mean Jake would have to admit it wasn’t just the memory loss that was different.

His therapist had suggested the memory loss could be stress related, or due to his poor sleep habits, adding he should see a specialist if he was truly concerned. Jake never did.

There were other things. Mood swings. Heightened emotions. Even…moments of enlightenment.

He wasn’t ready to tell anyone those things.

Jake had secrets.

He continued into the kitchen. Abby was there, her back to him, intentionally or not. She wasn’t quite his wife at the moment, and she wasn’t his ex-wife. She was, he supposed, just Abby.

“I’m taking off,” he said.

She turned to face him. That helped.

“Okay. Have a safe trip.”

He tried to read her and struggled. Ironic, he thought. Suddenly I can read the emotions of strangers, but Abby is a brick wall.

“Thanks.”

They locked gazes, and a thousand words died unspoken between them.

Jake walked over and gave her a hug. She squeezed back, but not as hard as he wanted.

He let go, left the house, and drove to the airport as the first few drops of rain spittled from the Massachusetts sky.

Jake had to accept he was a different man now. Different for so many reasons, and still changing every day. He might not be able to forgive himself, but he was starting to learn to accept.

I’m going to make things better, baby. I promise.

Inside the airport terminal, a sea of people swirled around him, and for a moment, Jake fought against breaking down and crying. He managed to keep it together.

Still, one tear escaped.

***

Goddamn if it isn’t happening again.

Right here in the airport terminal, a sudden burst of emotion, coming from nowhere. I have no idea what triggers it, if anything at all, but here it is, spidering up my chest and flushing my face. A wave of heat, and a moment, always just a moment, where I have to force back tears. A single tear snakes down my cheek, and I wipe it away.

I rarely used to cry. Maybe once a year? And now…I’m a mess.

The thing is, it’s not even sadness. Not exactly. It’s more like a sudden, profound understanding of something, a sense the universe just contracted a fraction smaller around me, and in the process, I become larger within it and have more of a sense of place. Of purpose.

I remember taking a Psych 101 class in college and learning about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. We learned the ultimate goal, the greatest need, was self-actualization. Its definition always resonated with me: The realization or fulfillment of one’s talents and potentialities. I remember thinking for so long, how is it possible to completely fulfill all of your potential? How would you even know?

But now, in the moments where sudden emotion threatens to buckle my legs, it’s exactly how I feel. As if I’m reaching my potential, even when I can’t point to anything that’s changed about me. Like I’m standing at the podium, having a gold medal hung around my neck as the anthem plays, but I haven’t even gotten up off the couch.

Steady yourself, Jake.

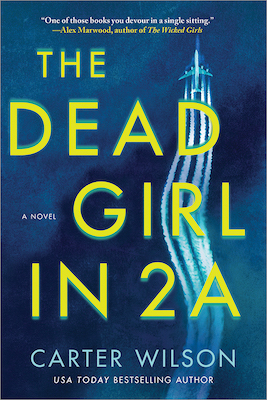

I board the 757, giving the outside of the plane a light tap as I pass through the doorway. Superstition of mine. Touch the plane gently, pay a little respect, and she’ll get me to my destination in one piece.

Today, that destination is Denver.

The flight attendant at the front of the plane nods and smiles, but there’s exhaustion behind her well-worn smile, desperation just behind her blazing, sea-blue eyes. She’s in some kind of struggle. I don’t know what it is, of course. But I know it as certain as I’m breathing.

Last year, I wouldn’t have noticed anything about the woman beyond the half second she smiled at me.

A lot has changed in the last year.

First class, seat 2B. I haven’t flown first class in years, but my client insisted. I didn’t argue.

I place my leather bag in the overhead bin, slide it to the left, then reach for my noise-canceling Bose headphones. After slipping them on, I take my seat.

I thumb on the headphones, and the ambient sound around me is sucked away, as if I’ve just been dropped inside a snow globe. Then I navigate my phone to a playlist containing only the recordings of thunderstorms. I know each track and can almost predict the violent thunderclaps as easily as the hook from a song. My go-to is a tropical storm, where nestled within the hiss of a rain-forest downpour are the metronomic calls of some exotic, lonely bird. In my mind, the bird is telling his mate to find shelter because the rain is exceptionally fierce and unrelenting.

The pang of emotion has subsided, but I know it sits close to the surface. I wait for it as I would a hiccup, in anxious anticipation. Nothing comes. Breathe in, hold, breathe out, then glance around me. Passengers file in, and each who passes leaves a trace of energy behind, like a dust mote of dried skin, clinging to me. Collecting. This woman is pleased with something. That man is frustrated. A child is scared.

All this emotional noise. I can’t escape it.

Last year, I wouldn’t have noticed a thing.

A sudden flash of Em’s face in my mind. Strange, in my mind, I don’t see the scar.

Thunder rumbles deep in my ears. The sound of a steady, digital downpour. I look out the window at the tarmac, where actual lighter rain falls. Cold, steady drizzle. Not common for Boston in October.

I give myself another memory test. What was the weather yesterday? I close my eyes and think about it, feeling the tendrils of panic swipe at me as my brain freezes. Then it comes. Cloudy. Maybe sixty degrees. Okay, good.

The accident with Em isn’t the main reason Abby and I separated, though the stress of her continuing recovery finally broke us. No, the real issue is I’m losing my goddamn mind, yet a part of me embraces the process. Abby’s been trying to help, but I keep her at a distance. She’s worried about my memory loss and my mood swings. I’m too young for a midlife crisis, she says, and too old for puberty. She Googles my symptoms, reporting back to me dismal potential diagnoses like early-onset Alzheimer’s, or even borderline personality disorder.

I’m too young for a midlife crisis, she says, and too old for puberty.

Abby thinks the accident caused my behavior change, but the accident was in January. She knows this all started happening a good month before that. Besides, the accident barely hurt me, just a bloody nose from the impact of the airbag. It was my little girl who took the brunt of the damage.

She shouldn’t have been in the front seat, Jake.

I know. I know.

What were you thinking? What’s wrong with you?

I don’t know.

She could be dead, Jake. Dead.

Goddamn it, don’t you think I know that?

No, the accident isn’t the cause of the things happening to me.

I look down, aware that I’m doing it again, sliding my wedding band back and forth along my finger. What’ll happen if there’s no longer a ring there? Maybe it will be like a phantom limb, something I’ve lost but can still feel. An itch of regret.

A woman standing in the aisle is talking to me. I lift the left cup of my headphones.

“Hi, that’s me,” she says.

My seatmate. 2A. She smiles and points to the open seat. She seems nervous.

“Of course.”

I stand and let her in, and as she passes within inches of me, I catch her scent, thin traces of flowers layered within something I cannot at first identify. It’s distinct, and it takes me a moment to place the other smell, and while I’m not positive, I think it smells like mosquito repellent. But it’s not the actual smell that jolts me. It’s the memory of the smell, fleeting but visceral, a déjà vu so powerful, I could be in a waking dream. I try to hold on to it, explore it until I can pinpoint the memory, but it washes away within seconds.

Isn’t that something they say? Smell triggers memory more than any other sense?

As she sits, I try to look at her without staring. About my age, I’m guessing, mid-thirties. Perhaps younger. Kinked red-brown hair, which falls well past her shoulders. Slim and rather pale. She seems out of time, as if her looks would be better suited for a character in Les Misérables.

I return to my seat, buckle in, then edge up the volume on my headphones. The rumbling thunderstorms drown out the safety demonstration and the roar of the engines as we take off, but my attention is focused on 2A the entire time. I don’t talk to her; she doesn’t talk to me. I order whiskey; she gets water.

I reach for my drink as I remove my headphones, no longer wanting to hear the rain or anything else. The cabin lights are dimmed. My seatmate and I both have our reading lights on.

She’s writing in a journal. Left-handed. I steal sideways glances from two feet away. She seems unaware of her audience.

The sense of memory slams into me a second time, more powerfully than before. This is especially jolting because memories have been sliding away rather than appearing lately.

I look at my arm, which is suddenly washed in goose bumps.

Jesus, what is happening?

There’s something else I never would have done a year ago, and that’s start a conversation with the person on the plane next to me. But the familiarity of this woman is so intense that I’m barely aware I’m speaking before I actually hear the words coming out my mouth.

“Excuse me, do I know you?”

__________________________________