One thundery afternoon in 2019 a kayaking trip with a friend was called off due to the weather, and I found myself at home instead, observing the time-honoured tradition of falling through a YouTube rabbithole. Seeking some vicarious watery adventure, I found myself watching the footage of Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology Team diving into the shipwreck of the Victorian ship, HMS Terror. The location of the HMS Terror and her expedition partner, HMS Erebus, were the subject of ferocious speculation since the 1840s, and their whereabouts were discovered in 2016 and 2014 respectively. The video of the divers going down into the ship is eerie, otherworldly, and strangely moving due to how well-preserved the wreck is. The footage that lingered with me long after watching was the Delftware dishes, still sitting on the shelves.

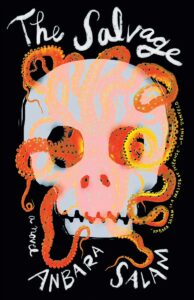

This image helped to crystallize a book idea that I’d been considering about a rundown Scottish seaside town, and the two ideas clicked together to become The Salvage. The novel is set in 1962, and follows a marine archaeologist, Marta Khoury, as she travels to a remote Scottish island to dive down to a Victorian shipwreck recently towed back from its final, doomed voyage to the Arctic. That one afternoon on YouTube launched me into a year-long obsession with the haunting appeal of shipwrecks and the turbulent history of polar exploration.

Of course, I’m far from unusual in my interests—shipwrecks have long had a hold on our collective imagination. A shipwreck represents civilization and the wild simultaneously. It is the contrast between the grandeur of their enterprise and their ultimate humbling at the hands of nature that makes shipwrecks Romantic in the true sense of the word. They are a testament to the spirit of adventure and the tragic consequences of human hubris.

In The Salvage, the ship at the heart of the novel began its voyage to the Arctic in 1846, and I chose this date thinking of the launch of the HMS Terror and HMS Erebus, which set sail a year earlier in search of the Northwest Passage, captained by Sir John Franklin. I was considering how the fictional ship in The Salvage might have been lost around the same time as the Franklin expedition and so its fate passed unnoticed by the wider world. Franklin’s expedition set sail in May 1845, and when no word of the ships was received after two years, the families of the crew began to be concerned. Could the vessels be stuck in the ice, in need of supplies? Or perhaps they had abandoned their ships and were awaiting rescue in an Inuit settlement. Franklin’s wife, Lady Franklin, was the most active public advocate that the men could still be found alive, and that the British public had a duty to attempt their rescue.

Over the next nine years, at least fifteen search parties were dispatched to look for traces of the lost ships. Some of these, like an 1853 expedition led by Elisha Kent Kane, found themselves also frozen in Arctic ice and forced to abandon their own vessels. These astronomically expensive and logistically complicated search parties were funded by the British government, private donors and campaigns led by Lady Franklin. The mystery of the fate of the men became something of a public fascination. Magic lantern shows were produced to depict the search efforts, psychic mediums in the US and the UK claimed to have made contact with the crew, folk ballads honoured the pain of Lady Franklin’s grief, Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens collaborated on a play, The Frozen Deep about the expedition.

Nine years after the initial launch, in October 1854, the explorer John Rae published his account of interviewing Inuit witnesses in the Times (UK), who had encountered bewildered and frail white men near where the ships had last been sighted. Following the testimonies, Rae wrote, “From the mutilated state of many of the corpses and the contents of the kettles, it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last resource—cannibalism—as a means of prolonging existence.”

To a British Victorian readership, a heroized expedition being reduced to an undignified, cannibalistic demise in the Times was unseemly at best, scandalous at worst. Charles Dickens was so outraged at the idea that this reportage was based on evidence provided by “savages or half-savages” that he wrote a two part refutation of Dr Rae’s account, “The Lost Arctic Explorers,” in Household Words. Dickens’ reaction was representative of a British public unwilling to puncture their visions of the upright men of empire based on oral Inuit testimony. The Franklin expedition, like many Arctic voyages, took place in the long and dark shadow of colonialism, and exploitation of and disregard for indigenous knowledge was rife.

In 1858 Lady Franklin commissioned yet another expedition which this time was able to locate some of the items the crew abandoned, which were almost horrifying in their mundanity. The leader of the expedition, Francis Leopold McClintok, notes the men had carried “about four feet of a copper lightning conductor” as well as towels, toothbrushes, soap, silver cutlery, and embroidered slippers. As Sarah Moss writes in Scott’s Last Biscuit,

“It is hard to imagine a better emblem of alienation than the curtain rods dragged for miles across the snow in a boat, only to lie beside the skeleton of an exhausted officer, along with three different kinds of silk handkerchief.”

The Franklin expedition crew buried on Beechey Island were examined in the 1980s, and the investigation team discovered higher levels of lead in their hair and nails, indicating that their tinned provisions were toxic, which perhaps affected their mental state and physical deterioration. The autopsy of John Torrington, one of the party, was so eerily preserved that it spooked even the team of forensic anthropologsts. As Torrington’s coffin was unearthed, the weather coincidentally worsened so severely that the crew were sufficiently rattled to halt work for the day. During the autopsy, unnerved by the preservation, the lead medical examiner Owen Beattie, felt compelled to cover Torrington’s face.

The Franklin expedition has had a long afterlife in popular culture. One of the most well-known works is the horror novel The Terror, by Dan Simmons, which was published in 2007 and in 2018 was developed into an AMC series in the USA. For the AMC show, the production team called in expert help from the model ship building community to recreate HMS Terror. This was so meticulous that it helped to inform understanding of the real vessel. When the recreated ship built illuminators—a kind of reflective glass porthole—into the upper deck, they realized they would not only have allowed natural light from above to filter below deck, but during the long Arctic night, they would have allowed lanterns below deck to be seen from above. This was one surprise takeaway from writing a novel about a shipwreck: the expertise of the model-building community should never be underestimated.

The Salvage itself is not a novel about, or even directly based on, the Franklin expedition; but it was informed by the tragedy of the ships’ final voyage as well as the kind of myth-making that takes place when a community at home is left without news of their polar-bound heros, and feels an obligation to fill in the gaps in the most heroic way possible. The novel was also inspired by the tangled colonialist web that binds stories of Arctic exploration in this period, and how artefacts from shipwrecks of this time speak to an unacknowledged debt owed to Inuit communities already indigenous to the areas “discovered” by western profiteers.

The wreck of the HMS Terror and the HMS Erebus are still awaiting full exploration. As in The Salvage, there is the remote chance that due to low temperatures and low oxygenation at the sites, paper documents from the voyages could still be uncovered and preserved. For now, their wrecks remain, tantalizingly, submerged, their final stories yet to be revealed.

***